Mexican drug lords infiltrate the media

In Mexico, drug cartels have infiltrated the media to the point where journalists have virtually stopped reporting on the all-engulfing drug war in an act of self-preservation. Helle Wahlberg, IMS, reports from the Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Kyiv

“One of the first victims of war is the truth and one of the first actions of media during a war is self-censorship. This is especially true for the undeclared drug war that Mexico finds itself in right now,” says Ana Arana, Director of Fundacion MEPI, a foundation that promotes investigative journalism.

Many Mexican journalists have “self-censored,” choosing to refrain from reporting on the cartels to avoid problems.

The silencing of media

More than sixty journalists have died since the Mexican authorities began their war on drugs in 2006. Speaking on the issue of safety of journalists at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Kyiv, Ana Arana painted a chilling picture of the situation of media in Mexico today.

Despite the fact that the drug war in Mexico has spiraled out of control with thousands of casualties, there is hardly any reporting on the violence permeating the country.

In 2010, MEPI carried out an investigation looking at the impact of threats and attacks by drug cartels on media in 60 per cent of the country. MEPI found that the drug cartels had infiltrated most media in Mexico – and that only two out of ten stories reported were about the drug war. This, despite that fact that the drug war is estimated to have cost the lives of more than 35,000 people since 2006.

Drug cartels dictate news agenda

Over a period of six months, a 12-person team investigated existing data on attacks and threats against media, gathered new data and monitored 11 local newspapers around the country for their coverage on drug-related violence. The team also hired correspondents in cities around Mexico who would deliver personal accounts on how they were reporting and any challenges they might face.

During a trip to the border town Tamaulipas, a main hub for drug transfers into the US, journalists told Ana Arana that they were not allowed to write anything drug-related (May 2010). Every three months the journalists had to meet with representatives of drug cartels and were told what to write. They were reluctant even to cover deaths by traffic accidents as they could never be sure if they were drug-related. In one year there had been 573 gang-land slayings in Tamaulipas. Only two of these were reported on in the local papers of the areas.

Social media not an alternative

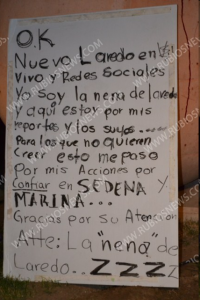

In many other countries where media is being repressed by authorities or other powerful groups in society, there have been examples of finding a new-found freedom of speech in the space offered by social media. This approach has also been taken by some reporters and citizens in Mexico, who have turned to Twitter, Facebook and blogs to find an outlet for reporting on the violence. However, within the last year, drug cartels have infiltrated social media and managed to find the identity of some of the Twitterers who have been tortured or beheaded.

Need for new story-telling methods

What, if anything can be done to improve the safety of journalists in Mexico and restore a reliable flow of information to the public?

“There is a need for early alerts, somewhere to which journalists can report that they are being followed and get help to escape,” says Ana Arana.

“We also need to find new ways of reporting the stories, for example by using new tools for visualising data through maps showing the impact of the threats of cartels on media and civil society. 70 – 80 per cent of the population does not know what is going on. Safety training of journalists could involve teaching them new methods of reporting.”

Unfortunately, a bad situation for media in Mexico is set to worsen with the prospect of elections next year, according to Ana Arana.

“What happens in places such as in Mexico is that the press is caught in the middle. They can either go with the drug cartels, with the army or with the authorities. Either way you are caught.”

This report was filed from the Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC) in Kyiv, Ukraine taking place from 13-16 October. The conference which IMS is helping to organise and fund, is a platform for journalists from around the world to exchange experiences, expand their network across borders, and get new ideas.