Blog

The Square of Change

The Square of Change project features the stories of 10 people whose lives changed through the community they found in a Minsk courtyard in the wake of the Belarus elections in August of 2020.

Queues at polling stations, an app to make sure every vote was counted, excitement and a sense of unity, arrested observers, vote-rigging reports. Detentions by day followed by military vehicles in the streets, flash grenades, batons and rubber bullets against unarmed protesters at night. All of that was 9 August 2020, the day when presidential elections took place in Belarus. It divided the country into “before” and “after” and will go down in modern history books.

For three days the internet hardly functioned throughout Belarus. People phoned each other or asked random passers-by about what was happening in the country. When the internet was restored, the information about unprecedented violence on the part of law enforcement shocked the country and the world.

On 12 August, women dressed in white holding flowers formed human chains to express solidarity with the victims and stand up against the violence. The women-led campaigns set the tone for ensuing peaceful protests, which quickly evolved into solidarity marches and mass demonstrations. 16 August saw the largest rally in Belarus’ history, with between 300,000–500,000 Belarusians gathering in the hot sun to express their solidarity with the victims and make a stand against the authorities. The mass demonstrations continued until November 2020.

The Square of Change is a story of a Minsk courtyard community, which became a symbol of friendship, support and overcoming alienation. At the same time, this is the site of confrontation between the courtyard residents and police officers. The latter repeatedly arrived at this residential district to destroy protest-themed drawings and white-red-white ribbons.

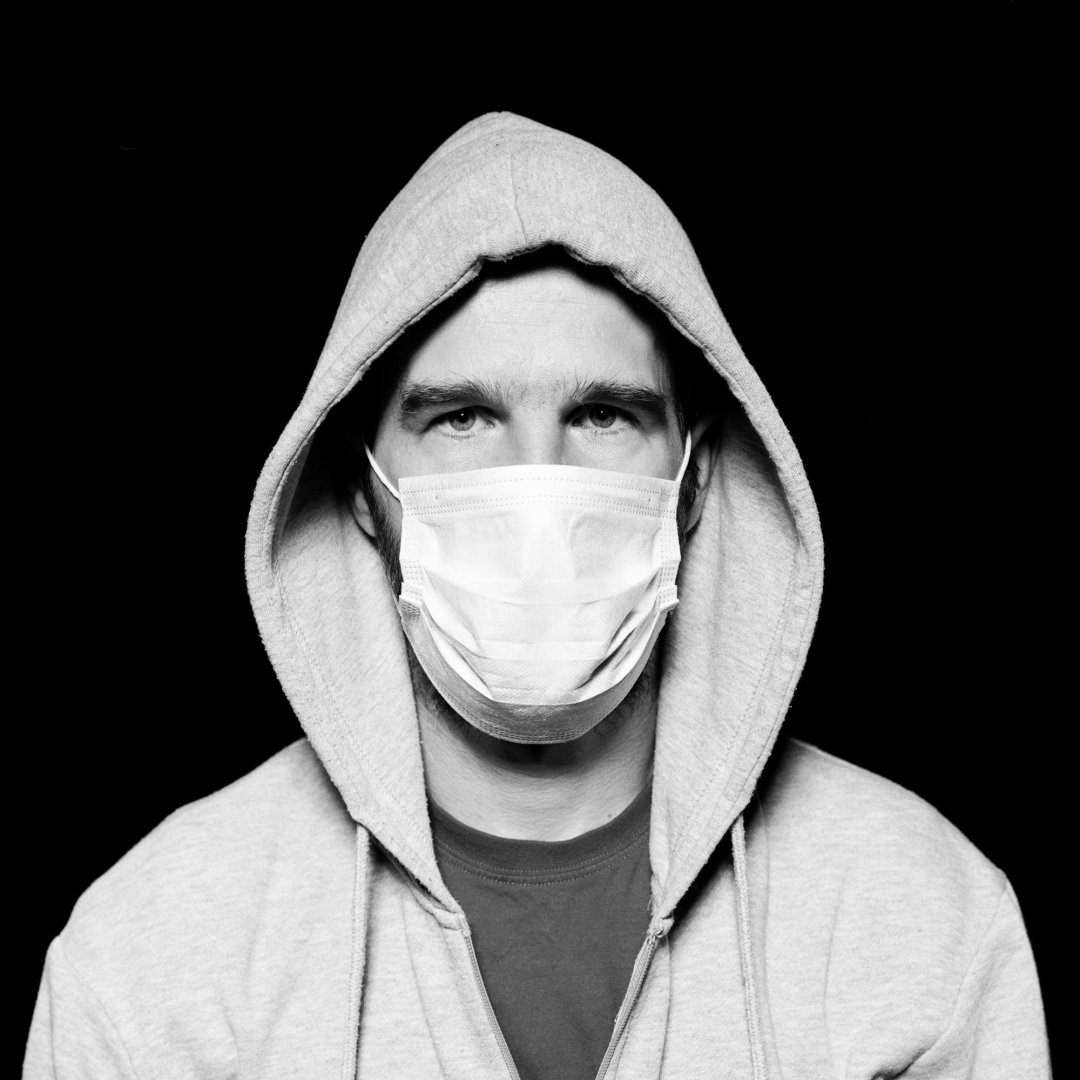

The Square of Change project participants are wearing face masks (and that is not just a Covid-19 safety precaution), the real names of some have been changed. Some of them were detained by the KGB, some had a narrow escape, and some will always remember the day when their neighbor Stepan Latypov was arrested for protecting the mural in the courtyard, and the night when Roman Bondarenko was kidnapped from the Square of Change and beaten to death. Each of them can be prosecuted for their stories.

Marina, who found support in her neighbours

Early on, I spontaneously took part in solidarity chains, stood in front of factories expressing support for the workers, as well as near the buildings of the state TV channels CTV and ONT. This was my way to stand up against the lies, lawlessness and brutality of the authorities. After the DJs of Change mural had emerged, I realised I was not alone and that support can come from the amazing neighbours and guests of the courtyard.

Originally, I viewed the Square of Change as a symbol of freedom, a small island of sanity amidst the madness. Today, along with other areas where communities have been formed, the Square of Change for me stands for hope. I keep hoping that we will win soon and the culprit Lukashenko and his accomplices will end up in prison.

Vasya, who carried a flag from the Square of Change to the largest rally in Belarus’ history

On those dark August days people would literally go outside to fight as law enforcement officers unleashed a real battle in Minsk’s streets. I was burning inside, I wanted to get out on the streets and join the protesters, but I looked at my son and couldn’t let myself do that. I was suppressing that urge because of the fear of what might happen to my son and wife. That fear was paralysing me and I couldn’t work, had difficulty sleeping and it seemed that as soon as I woke up, it would all be over.

I could only watch the protesters from my balcony and cheer the young guys disappearing in the dark. One of them left a handmade white-red-white-flag in the courtyard — it was a white bedsheet with a red stripe in the middle. He tied it to a lamp like a scarf around the neck.

And then the ball got rolling, with the first DJs of Change mural in the children’s playground, white-red-white ribbons tied to a fence and a huge white-red-white flag hung up on our house.

The first women-led campaign against violence that took place on 12 August was a ray of light. The confrontation shifted from night-time to daytime. I recovered my strength, and on 16 August I went to the first Sunday march at the Minsk Hero City Stele. People were coming to the Stele from all over the city. I was there with my neighbours. We took the flag down from our house and carried it together.

The white-red-white flag is the symbol of those who disagree with the current government and carrying the huge flag from our neighbourhood was a great honour for me. I felt incredibly happy. After the Stele, I carried the flag up to the Government House and then put it back on its spot.

The flag kicked off a real partisan war. When the authorities took it down, we put up a new one, when they would paint over the mural, we would clean it up or repaint it. The confrontation started several months ago and continues to this day.

Alex, who “did what he should” at J:MORS’s concert

The Square of Change hosted a lot of cool concerts, I helped organise many of them, but the one that sticks in my memory the most was the performance by Vladimir Pugach, the frontman of the well-known band J:MORS.

On the day of the concert, the Square of Change was under patrol, with three police officers in balaclavas guarding the wall where the DJs of Change mural used to be. Back then, the police observed at least some laws – they didn’t let us connect the equipment, but were ok with us gathering and chatting, drinking tea or coffee, singing and dancing.

The “guards” told us that if we turned on the speaker near the mural, they would leave and special police units would arrive instead. A guy who was involved in inviting J:MORS came up to me and said: “Go to the stairs at the back entrance of the house at 1 Smorgovsky Trakt. Don’t ask questions, just do what you’re told.”

We managed to bring the equipment up to the common balcony on the second floor without being noticed. By the way, you can only get there using a magnetic key. Vladimir Pugach performed on the balcony, and it was very unusual and spectacular. It was also a surprise for the Square of Change’s residents and guests, as well as for the police. When the concert was drawing to a close, we saw policemen, led by two plainclothes men, entering the building through the main entrance. It was obvious that they wanted to get to the stairs via other floors. About 12–15 people simultaneously ran up to the door that gave access to the balcony and blocked it, protecting the musician. Of course, the encounter with the police was nerve-wracking and intense, however no arrests were made and Vladimir Pugach could leave.

Polina, who was kidnapped in the street by the KGB

I visited the Square of Change for the first time about one and a half, two weeks after the election. This was when Minsk suddenly saw the rise of courtyard communities. First, there was a flashlight campaign: at 21:00, people turned their flashlights on and shouted “Long live Belarus” out of their apartments’ windows. Our courtyard was quiet, so my sister and I took white-red-white flags and went to the high-rise blocks in the Square of Change and started shouting together with the residents, but from below.

Very soon the Square’s core activists became my family. Together, we took part in campaigns, made protest-themed drawings on the wall of a facility in the courtyard, had tea and attended concerts. For the first time in my life, I realised that a person’s social circle can include not only family and friends, but also neighbours. And each time strangers try to deprive us of our place, of our little country, just because they received an “order from above”, I feel overwhelmed with resentment. This is a gross infringement on our space, an attempt to take away the joy of socialising and the opportunity of just having a good time together.

I was detained three times, the latest one by the KGB. I was on my way to a tailor shop when two sturdy plainclothes men attacked me, pushed me into a car, put a bag over my head and drove somewhere. I realised I was taken to the KGB a bit later, when I was being led by the arms up the stairs with my eyes blindfolded and when I felt I was walking on a carpet strip along a hallway.

The first thing I saw when they brought me into a room and removed the bag from my head was the photocopies of my parents’ passports. I was shown a video where I was marching along the Winners’ Avenue together with hundreds of other Belarusians. I was asked about radically-minded people, courtyard activities, motivations, my parents and acquaintances. They also offered me brandy and coffee. Then, a highly professional ideologist for two hours tried to gently, cannily and non-violently “talk sense” into me. Once the talking was done, I was taken to the Internal Affairs Department of Minsk’s Sovetsky district and then to the Criminal Detention Centre on Okrestin street. Two days later, there was a court hearing and I received a 10-day sentence.

Di, who knew the activist Roman Bondarenko, who was kidnapped from the square and killed

The fact that Roman wouldn’t survive was already clear to me that morning. I was messaging with his mother, and she told me that the situation was critical and that Roman was in a coma. She couldn’t say he hadn’t long left to live, she believed there was at least one chance in a thousand. Everyone who phoned or texted me knew it was hopeless, and I was taking that very hard.

In the early days after Roman had passed away, I felt hate towards all law enforcement officers and everyone involved in his death. I wanted to find them and get revenge. I wanted to go back to the day he was abducted, because we spoke ten minutes before that happened. He told me that he had quit his job at a store and was feeling great and that soon he would be coming to our courtyard every day, as he lived not far from the Square of Change. His words stuck in my memory.

Roman was a very sincere guy, one of those who would always give a helping hand if needed. If he was asked to do something, he would literally go out of his way to help, while being very humble.

Roman didn’t have many close friends, but those who knew him never spoke badly of him. Just once there was some misunderstanding in the Novoe Ozero (New Lake) Telegram group chat (it consists of the residents of the houses adjacent to the Square of Change) because of the fact that Roman had served in the Special Forces. He was even removed from the chat because of that, but then taken back.

How did we meet? One day in early September, when my neighbours and I were in the Square, someone sent Roman’s photo in the group chat saying he was a police informant. I told that to a neighbour standing next to me and she came up to him and asked him straight out if that was true. He looked at her with his eyes wide open and said: “No, I’m Roma!” He was wearing a black hoodie with the hood on his head and standing there alone. Roman always kept his distance without coming up close to anybody, but it was obvious that it wasn’t his first time in the Square. Roman was clearly interested in what was going on there, he liked the place itself and everything that was happening in the Square of Change.

Andrei, who protected the Square of Change from the first attack of police informants (“tikhari”)

It was about 22:00. There were almost no people left in the Square of Change, apart from two girls and two guys painting the benches white-red-white. Suddenly, about fifteen people with their faces covered emerged from the dark. The “tikhari” went up to the girls first. They pushed one of them so hard that the bucket with red paint hit her in the face and chest. They also broke the camera of the other girl who was filming a video. I was shocked. When I saw the girl with her face covered in paint I went mad. How could I just be standing there and watching some bastards kicking our friends without any warning or reason?

I went up to one of them and said: “What’s wrong with you? Why did you push that woman?” I didn’t manage to finish saying that as I got a sharp blow to my jaw.

I passed out for a few seconds. As I was coming to, lying on the ground, the conflict between the “tikhari” and the two guys was escalating.

I realised those were plainclothes police officers. I don’t know whether they were from a District Department of Internal Affairs or an intelligence agency. Those guys looked tough. The situation was ambiguous – even though I was protecting my courtyard and my people, it was clear that attacking an informant would be equal to attacking a law enforcement officer. This is leads to criminal prosecution and a long sentence.

However, I sent a message to the Novoe Ozero (New Lake) Telegram group chat asking everyone to come out, and they did. Within five–ten minutes, about 50 people gathered in the Square.

A verbal fight broke out between the informants and local residents. We were standing there like a wall, with the mural behind our backs. They didn’t manage to destroy it and repaint the benches, even though they brought their own paint.

We called the police two or three times. Of course, they didn’t come because the people who came to the Square were obviously police themselves. We chased them away, and they were walking down the street followed by our amazing crew. We managed to stand up for our courtyard.

Kamilla, who became a concert organiser because of the Square of Change

The first time I came to the Square of Change was in mid-August, after the elections. The courtyard and the surrounding apartment blocks were decorated with white-red-white flags, people were shouting out of their windows and gathering on the playground. Very soon the meetings evolved into neighbours’ tea parties in the evenings. Gradually, event ideas started emerging spontaneously: “Let’s do this!” People were full of creativity, and all the ideas were picked up and brought to life as performances, concerts, photo and video projects and other activities.

To be honest, I can’t even remember now who performed and when; so many artists and bands playing in a regular yard was something that had never happened before in Minsk’s history. Before the Square of Change, I wasn’t familiar with so many Belarusian musicians and obviously didn’t think I could become a concert organiser.

I really liked the performance of the rock band Nizkiz. So many people attended! I couldn’t watch the concert as I wasn’t able to see the musicians through the crowd, I was just listening. What fascinated me the most was a gig by Petlia Pristrastija — the band created an incredible atmosphere in the courtyard.

Organising concerts is like running a marathon at a really fast pace. “I need to answer this.” “A mic and speakers need to be here, lights need to be there.” “Now, where is the tea?! This is urgent! The musicians are freezing.”

The most memorable event that we organised took place on Minsk City Day. The Square of Change hosted a show featuring folk dances and games, and the Square’s residents and guests prepared so many treats that we didn’t have enough tables to put them on. In the evening, there was a concert. Meanwhile, the DJs of Change mural was painted over with horrible stinking bitumen, and the black wall was being guarded by police officers from the Internal Affairs Department of Minsk’s Tsentralny district.

They were standing and watching the festivities, apparently waiting for an order. Passing them by, I asked: “Isn’t it cool?” Two of the police officers smiled and the third one kept an angry look on his face. I thought to myself: “Come on, will you ever see a gig like that?”

Yulia, who saw the attack on Roman Bondarenko on 11 November

I looked out of the window and saw strangers near our fence with the white-red-white ribbons tied to it. They were cutting them off. I noticed that Tanya (who also lived in the Square of Change) was among them. I felt so angry that I rushed out to her to ask what was going on.

Among the “concerned citizens” was a woman in a red hoodie. I tried talking to her, asked if she enjoyed being promoted to cutting off the ribbons, mocked her, and she was responding to me. The others weren’t reacting.

And then I saw Roman. He was standing next to some other guy and holding a pizza box. I went up to him and said: “Well, here they go again, right?” We had a little chat and then started listening to what the police informants (tikhari) were talking about. Roman said to one of them: “That’s it, wrap it up.” He said that in a calm, quiet voice, without shouting.

“You’re looking for trouble, aren’t you?” the man responded. First, that man attacked the other guy by mistake, not Roman, probably thinking that was who was talking to him. A fight started. Roman was standing near the swings when a man ran up to him from behind, seized him, pressed him against a bar and pulled him down to the ground. Roman tried to resist but was hit. Then they grabbed him and dragged him into a minibus.

Two hours later, Roman was found unconscious in a hospital. A few more hours later, he was taken to the neurosurgery operating theatre.

Mama Sativa, who saw workers dismantling a civic memorial

On Sunday, 15 November, a march in memory of the people killed during the protests was announced. People were planning to march from the Pushkinskaya metro station, where Alexander Taraikovsky, a change supporter, was shot dead on 10 August, to the Square of Change, where Roman Bondarenko was abducted by unidentified masked persons on 11 November. Roman went out to the courtyard when they were cutting off the white-red-white ribbons tied to a fence by the Square’s residents. He was kidnapped, no one knew his whereabouts, and later he was found in a hospital with multiple injuries, including to the head. He died without regaining consciousness. On that day, a memorial emerged in the Square of Change. Thousands of people from all over Minsk kept bringing flowers, candles and lanterns to get through that tragedy together and express their grief.

I was very surprised by the fact that the memory march was attended by even more people than came to the Square in the first days after Roman’s death — the small children’s playground literally could not fit them all. I was shocked even more when flash grenades started being thrown at them. Some people even walked towards the police officers with their hands held up and they backed down, but then special police reinforcements arrived and things only got worse.

My friends and I were very lucky — we came home to have some tea and get warm. We were standing on the balcony and smoking when special police officers in helmets attacked the Square of Change from all sides. People started running away, but they were chased. Another group of the police officers besieged the Square, and the people who were near the memorial formed a chain trying to protect it. The police were communicating via loudspeakers and at some point the chief said that it was Tikhanovskaya who killed Roman. Everyone was outraged. Those who remained on the common balconies of the house at 1 Smorgovsky Trakt were shouting to the police chief out of their windows: “What? What are you on about?”

There was an entire police unit under our windows, and I was shaking cigarette ash down on them. I didn’t know that a few hours later officers of the Main Directorate for Combating Organised Crime and Corruption would arrive to search the apartments of the Square of Change’s residents. They arrested everyone who was standing near the memorial. However, I saw that some of them managed to escape, they were let through the police line. But those were women, elderly ones by the looks of it.

When they cleared the Square of people, they stayed there waiting for a clean-up. I think, Remavtodor (a public utility service) arrived. As far as the backstory is concerned, the workers were expected to remove the flowers and candles in plain clothes, but they insisted on wearing their orange uniforms to show they were at work. I was really impressed when the first worker who came to the Square put his own lantern down on the ground. And then they started disassembling the memorial, it took like two-two and a half hours. The workers were trying to pile up the flowers and lanterns carefully, without breaking anything. It was at least something that they dismantled the memorial not as brutally as they could have.

Tanya, who realised that special police officers are just boys in uniforms

I live in a house in the Square of Change and, together with my neighbours, I witnessed a lot of what happened there. Those events caused different emotions, from joy to pain, however each one is unforgettable, important and precious.

My most inspiring memory is when the courtyard residents hung a huge flag between the houses. The most tragic day was when Roman Bondarenko was killed, of course, as well as 15 November, when a march in his memory took place. Then, thousands of special police officers arrived at our courtyard. They threw grenades and basically occupied the area, checking people’s passports and arresting those hiding in the apartments of the Square of Change’s residents. This is when I gave up believing that adult men worked for law enforcement agencies. Those are just boys fulfilling orders. Up to the very last I hoped that there would be at least someone who would refuse to take people in a police van on a day like that. However, the uniform was just a disguise for pathetic cowardly boys.

Please direct all comments and questions about this project to Emma Lygnerud Boberg: elb@mediasupport.org.