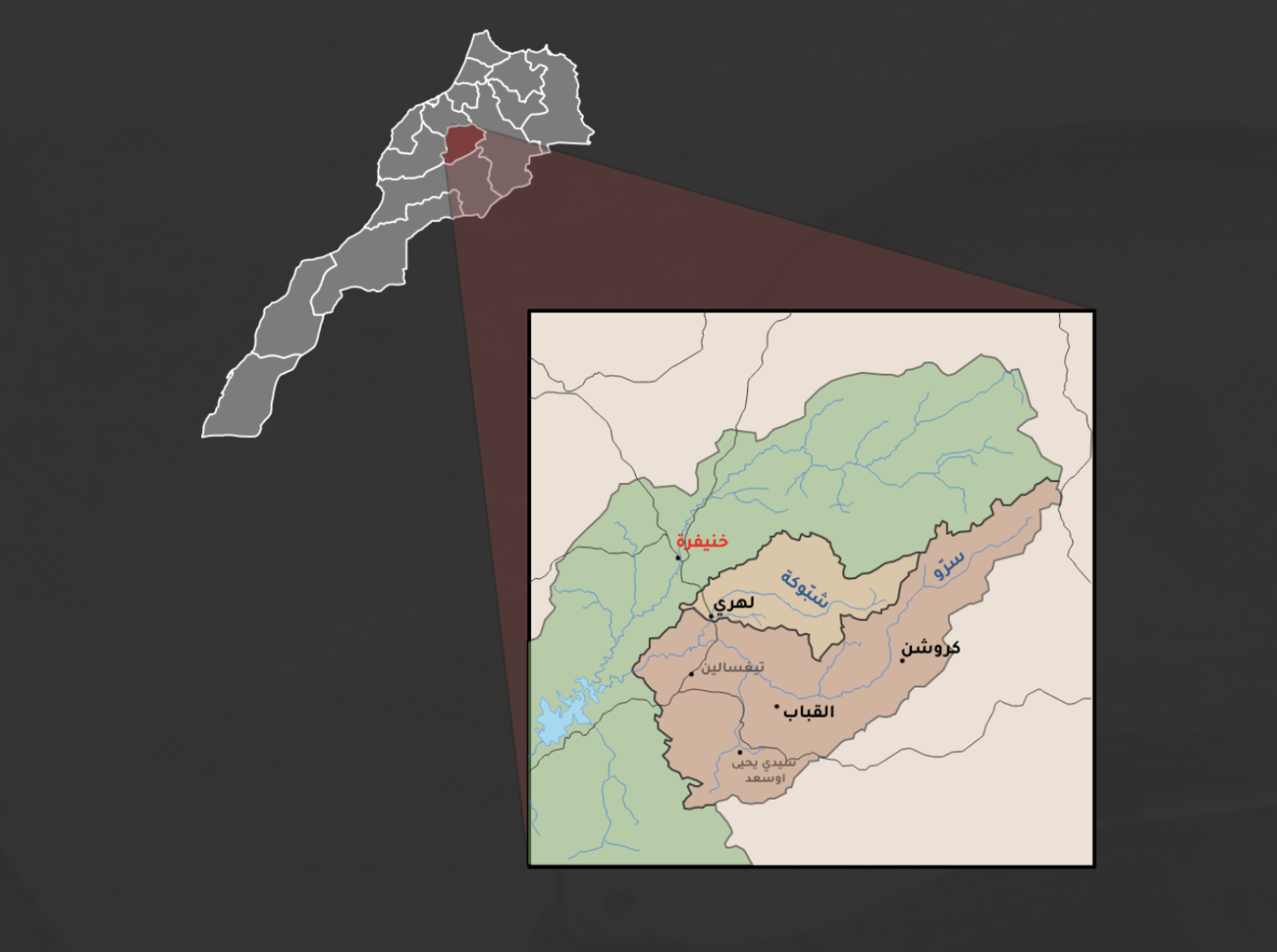

Dams and pumps drain Wadi Shbooka of its water in Morocco

Water is a necessity for life, but local residents living by the Wadi Shbooka river in Morocco saw it slowly drying up. Influential farmers had built dams and water pumps depriving herders and small farmers of their livelihood and destroying recreational areas by the river. Following the publication by ARIJ, the regional authorities in the area removed the pumps and other facilities mentioned in the investigation in response to citizens’ complaints.

By Mohammad Taghrout

Ahmad lives on the outskirts of Wadi Shbooka in the province of Khénifra in Central Morocco. On 15 May 2022, he woke up to the sight of dead fish along the course of the river where the water had dried up completely. He took a picture of the place with his phone and the circulated photo had angered the residents of the Lehri commune, at the same time the photo blew into the open a series of collusions and violations committed in the area.

This investigation was conducted with the support of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ). Founded in 2005, ARIJ has helped journalists adapt to changing technology in a constantly shifting political journalism landscape – in a challenging environment of press freedom and access to information.

The waters of Wadi Shbooka did not dry up abruptly; rather, this happened over stages when influential farmers built hillside dams and installed water pumps with channels that exceed ten centimetres in diameter, to divert water to their farms on areas that spread between 500 and 600 hectares to irrigate crops that need ample amounts of water, such as potatoes and beets. Their action has deprived the people living along the river banks of their livelihood based on cultivating orchards and providing water for their livestock in addition to depriving them from their recreational space, as dried streams become infested with insects after the fish stock disappeared.

Farmers have the right to benefit from river waters that are considered part of the public water domain, but they are not allowed to build structures within the valley or to divert its waters. This constitutes a crime and a violation of the law regulating the management of water wealth in Morocco. Small farmers, livestock herders in Lehri Commune and residents on both sides of the valley experienced the greatest harm.

The residents of Lehri protested against allowing the water of Wadi Shbooka to be drained away, and they sent written complaints to all the institutions involved in the management of water use and the environment. These were signed by 70 people who attached their national identification numbers to the signatures, and they called for “the urgent and decisive intervention against the illegal exploitation and the dangerous depletion of water resources, which stopped the water from flowing in the valley.” They alerted the concerned authorities to the violations by eight major investing farmers who installed equipment along the river unlike any they had previously seen, and they did this without obtaining licenses from the competent authorities. .

Mustafa Baali, a resident of Lehri, says that “the Adkhasal region includes a group of lands owned by powerful families who draw water from the valley and pump it to their lands. These were barren lands that were transformed into irrigated plots raising their rental price range to reach between eight and ten thousand Dirhams ($724 and $910), per hectare per year. Later, those so-called investors began to cultivate crops that require greater quantities of irrigation water, such as beetroot, potatoes and watermelons. Everyone started to pump water from the valley for distances exceeding six or seven kilometres through ten centimetre diameter pipes.”

The disruption of the flow of water in the valley will have repercussions on the simple livelihoods of the residents of Lehri and will deprive its livestock of drinking water besides leading to the ecosystem damage of the valley’s creatures and residents.

“The settlement of the residents of Lehri in the region is interlinked with Wadi Shbooka; they and their livestock would drink from it, and they would use it to irrigate their crops that formed their livelihoods. It is also the only outlet for the youth of the region since they do not have youth clubs, swimming pools or recreational spaces.” Says Abdullah Mahti.

Professor of life and earth sciences Al-Hussein Al-Showhani concurred: “This is not just about fisheries; rather, there is an integrated ecosystem, including fish, insects, birds and other animals that thrive on the waters of the valley.” He said that the Wadi Shbooka ecosystem was an incubator for “la truite fario salmon”, which lives only in cold, freshwater rich in oxygen. He added: “The female fish of the endangered types that live in Umm Al-Rabiee River would lay their eggs in Wadi Shbooka because the larvae of some fish and the small fish of some other species could not bear the high salinity rate in Umm Al-Rabiee River. Therefore, the females migrate to the upper tributaries of Umm Al-Rabiee River which had properties that allowed the fish to thrive.”

The appendix to the Annual Order Regulating Fishing in National Waters during the 2022-2023 Season includes a list of classified waters, placing Wadi Shbooka and its tributaries, including the sources, its confluence and Wadi Jinan Mas and Werg, in the top group of the waters where the Salmonidae species are found.

Professor Al-Showhani estimates that “Wadi Shbooka has distinct ecological characteristics not only in the region but also globally. Drying it up, or cutting its connection with Wadi Saru and disrupting the balance between the biological and the environmental field will accelerate the extinction of many species of fish that live either in Umm Al-Rabiee River or in Wadi Saru.”

Al-Showhani went further to say:

“We alerted the authorities directly to the threats that might be posed as a result to health in cows and sheep herds. The more dangerous part is that it would infect children because the percentage of insects in the Lehri area is frightening. If the water flow in the valley remains interrupted throughout the summer, children may develop skin diseases.”

Wadi Shbooka is one of the largest tributaries of Umm Al-Rabiee River, and it flows from Akelmam Nami’mi, a lake located 30 kilometres from the city of Khénifra at an altitude of 1,500 metres.

Article (28) of the Water Law No. (15-36) states “The following are subject to the licensing regulation: […]3- Establishing facilities for a period not exceeding ten years on public land with the aim of using the waters of the commons by water mills, water barricades or canals.” This licence is granted by the Water Basin Agency which controls the concerned public water sector, and in the case of Wadi Shbooka, the decision is up to the Water Basin Agency of Umm Al-Rabiee.

The oversight committee takes no punitive action

Two days after the river had dried out an investigative committee made up of the royal gendarmerie, representatives of the local authorities, the head of Lehri communal council and the local inhabitants’ representatives visited the region. This committee noticed that around 40 pumps have been erected by eight farmers who had not obtained licences from the Water Basin Agency of Umm Al-Rabiee.

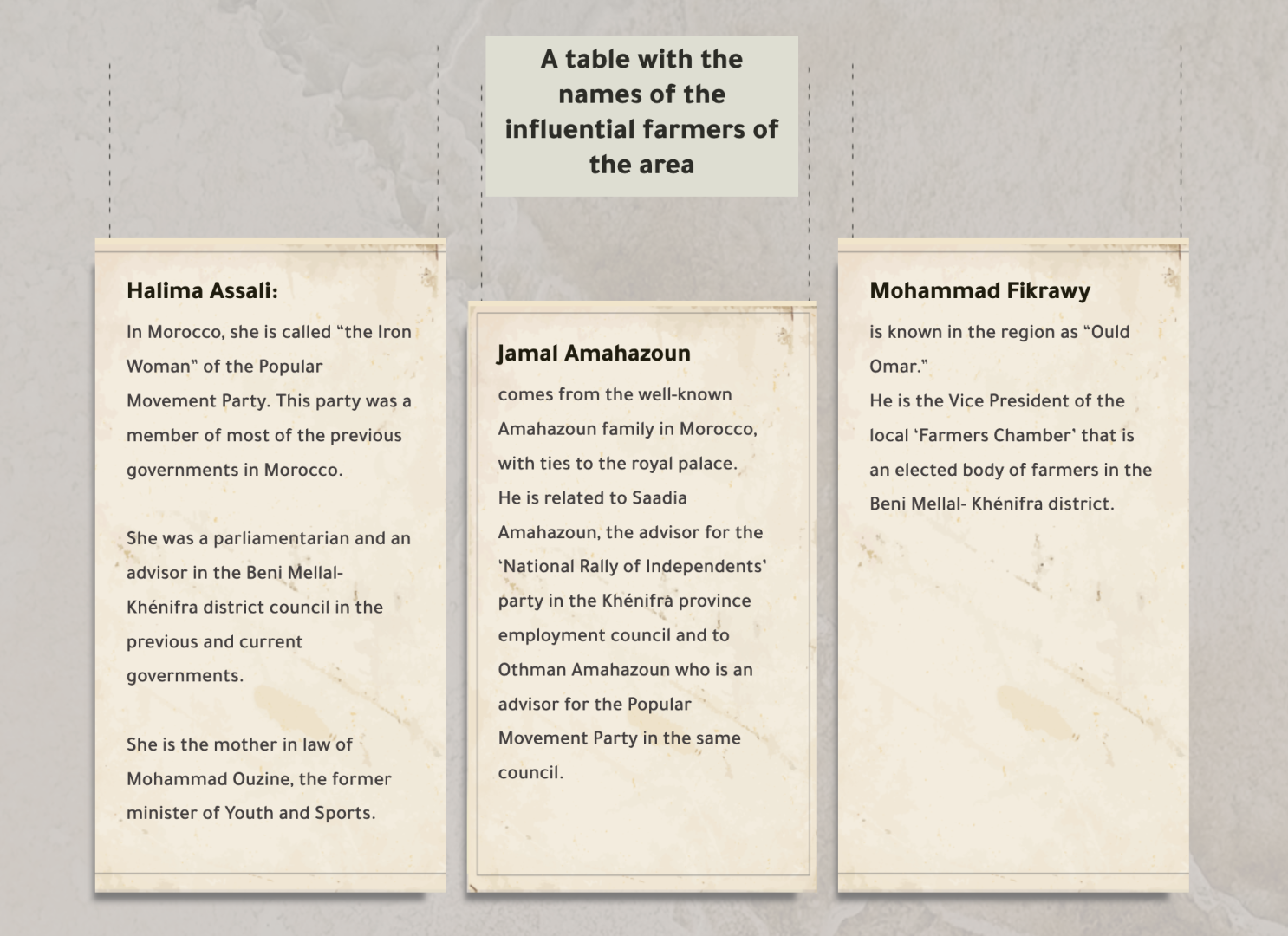

The committee stood by a hillside dam consisting of two cement walls in the middle of the valley, separated by an iron door that cuts off the water and changes its course towards a massive pipeline that directs water to the village of Mohammad Fikrawy, who is the Vice President of the Farmers Chamber. This is an elected body whose mission is to represent farmers and livestock breeders to defend their interests with the local, regional, district and national authorities.

Pressure to keep quiet

Mohammad Fikrawy, the Vice President of the Farmers’ Chamber, is also the proprietor of the hillside dam, its hydraulic installations and the commercial pumps powered by solar panels, filed a lawsuit against one protester accusing him of blackmail. In filing the complaint, he admitted to paying a bribe of 5,000 Moroccan Dirhams ($455) to persuade the protesters to put a stop to their complaints about his responsibility for draining the river.

We contacted Fikrawy repeatedly, and he agreed to more than one appointment to answer our questions regarding the lawsuit and the hillside dam, often stressing the need to meet face to face for him to answer our queries, but at some point afterward, he stopped answering our calls several months ago.

Eleven days after the river became completely dry, the socialist group in the Moroccan House of Representatives sent a written question to the Minister of Interior inquiring about the measures he intends to take to rectify the situation resulting from “the illegal use of the waters of Wadi Shbooka, which led to draining it and to the death of its numerous creatures.”

The parliamentary group of the Socialist Union of Popular Forces (which sits in the opposition) considered “the use of pumps and the construction of what look like small dams is not something that should go uninspected, especially if they are not licensed by the competent authorities. Therefore, condoning it is not only a violation of the law but a total disregard to it and causes deliberate harm to the residents of Lehri and its environment as a whole, especially given the climatic conditions the Kingdom has been witnessing this year.”

The government did not reply to the parliamentary question, and nothing happened since the investigation was made public, although Article (40) of the Water Law forces the offenders to redress the damage they caused to the land and river at the expense of the offenders.

Article (40) of Law No. (15-36) regarding water states the following:

“With regard to the added construction on the watercourse in violation of the requirements of this law, the Water Basin Agency […] may order the violators to demolish them, and when necessary, to redress the places to their original condition within a period of thirty (30) days starting on the date of delivering a notification of receipt to those concerned. Upon the expiry of this period, the Water Basin Agency may automatically carry out these actions at the expense of the violators.”

To date of completing this investigation, no institution has come up with any official clarification that explains the situation. Nine of the collective advising members of the office of the local Lehri council who are elected representatives of the residents issued a statement in which they did not propose any solutions to the problem; instead, they were satisfied with just condemning the protests for their infringement on investors.

Four of the signatories are affiliated with the political party “National Rally of Independents”, which the Prime Minister Aziz Akhannouch belongs to, while the rest are from the “Authenticity and Modernity” and “Istiqlal” parties. Members of those three parties form the leading majority of the local Lehri Council, the Khénifra Regional Council and the government.

The “investment” argument

Abdullah Mahti

is a farmer from the Lehri commune.

He believes that “we cannot describe these (violations) as investments, since investments are supposed to be beneficial to everyone. We used to live in peace on subsistence farming that takes into account the peculiarities of the area and the water available for the cultivation of grains and not crops that drain the waterbed. This place does not have sufficient quantities of water for this type of cultivation, which they brought into the area.”

Resident of Lehri Mustafa Baali,

says that “the commune does not impose taxes, and the state does not receive any compensation for the exploitation of the shared water. The agricultural sector in Morocco is generally exempt from taxes, and the area is close to the centre of the city of Khénifra, so the crops harvested do not require large transportation expenses. Manual labour is brought from other regions, so the people of the area are left unemployed and do not benefit from the process. On the other hand, facilitations are given to investors who should normally be giving something back to the region like providing special funds for schools or repairing the roads. In our case, however, none of that happens, and they benefit from the water for free.”

Bouazza Lahou

Head of the collective council of the Lehri commune Bouazza Lahou justified the statement issued by the office of the collective council by explaining that it encourages investment that would enable those concerned to have a decent living and provide job opportunities. He did not like the idea of draining the valley completely, but he justifies the use of the water, so that other areas do not benefit from it alone. He said: “Other regions benefit from the water when we in Lehri have a priority to using it.”

Resident of Lehri Mustafa Baali,

Nassir Alawi

Agricultural engineer and research professor at the Hassan II Institute of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine Nassir Alawi believes that this cannot be considered an investment for the region. He added that the residents are shepherds, which is an essential economic activity for the area. As soon as the live stock shrinks, all of Morocco would also be impacted.

About the fact that farmers do not benefit from job opportunities created by the various so-called investment, Lahou contradicts himself when he says that “In the end, they are Moroccans, and this means that the labour force in the region is insufficient.” However, he added: “If labour is brought from outside the region, this would stimulate the region’s economy because even those workers buy goods or rent houses and help grow the local economy.”

Chapter (31) of the Moroccan Constitution states that sustainable development is a right for all citizens. Article (10) of the Framework Law (99.12), which serves as a national charter for the environment and sustainable development in Morocco adds that “sustainable development represents a fundamental value that should be integrated into the activities of all components of society.” The national strategy for sustainable development is based on seven basic conditions, the most prominent of which is ‘improving the management and preserving natural resources in a way that preserve the bio diversity of the area, through the sustained and integrated management of water resources, the soil and biodiversity of the region.

Water consuming crops in the age of water scarcity

A document on the hydraulic situation from January 2022 published on the official portal of the Water Basin Agency for Umm Al Rabiee states that rainfall decreased this year over the Umm Al-Rabiee region to just 0.6 millimetres in January, compared to 179.2 millimetres in the same month last year. Morocco witnessed lower quantities of rainfall this year as a whole, and the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water in Morocco has declared a “water emergency.” Therefore, the Ministry of Interior issued a circular to “walis” or local governors, local councils and workers, calling on them to take a set of measures to reduce excessive consumption of drinking water. It stressed the need to “stop any form of wasting water in order to preserve current resources and to ensure the equitable distribution of water for the benefit of all.”

Accordingly, the Moroccan Association for Human Rights in Khénifra has sent a letter to the Ministry of Interior calling it to work to “stop the series of water thefts from Wadi Shbooka.”

In the correspondence, the association stated that this depletion of water resources has been registered in the middle of last May. The Water Basin Agency for Umm Al-Rabiee issued two warnings and handed them to the local authorities in the region to be delivered to those draining the valley. That had prompted the residents to organise protests with the support of the Moroccan Association for Human Rights in Khénifra, but the situation remained unchanged.

Cultivating potatoes in Morocco usually takes place in three well-known areas dedicated to this crop in

In each of these regions, the product is ready to be harvested and consumed in the rainy season.

Aziz Aqqawi, a member of the Moroccan Association for Human Rights of the Khénifra branch, says: “The residents of Lehri tried to plant potatoes in January for the first time to be harvested as soon as the temperature begins to rise, and they found this to be a significant harvest. This year, the big investors noticed that planting potatoes in the area could provide profits, and they rented lands from the farmers of the area.” As a result, the river dried up in one year.

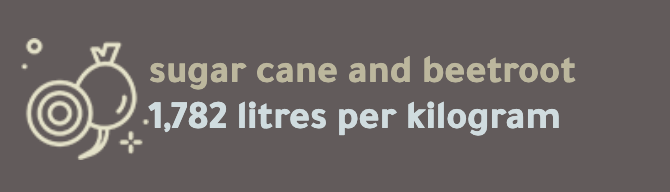

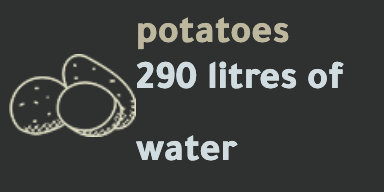

The Water Footprint Network is a non-governmental scientific organisation that calculates the water footprint of agricultural crops, that is, the volume of fresh water used in the production of a particular crop. This is usually measured over the entire processes and stages of preparation and production. The network estimates that the production of one kilogram of potatoes requires 290 litres of water while sugary products like sugar cane and beetroot require the equivalent of 1,782 litres per kilogram.

Agricultural engineer Nassir Alawi explained that “large areas of potatoes, beets and carrots have no place in Lehri. The risk with carrots lies specifically in the use of machines to grind the soil and sifting it to make it suitable for cultivation, and this affects the productive value of the soil and causes its erosion as soon as it rains.”

Our questions to the official authorities remain unanswered

We called the person in charge of communication for the Water Basin Agency for Umm Al-Rabiee, we also sent a request for information through WhatsApp, and the agency’s official email. We also filed an official correspondence in the Agency’s control office, asking for clarifications on the issue.

Also, we made several visits to the Khénifra province municipality, and to the authority in charge of communication and relations with the media there, in addition to filing an urgent request for information at the quality control office. Ten days passed and we did not receive any response, so we re-filed an official request again.

We visited the regional agricultural office of Khénifra only to be directed to the head of the agricultural and water department in the directorate who did not have the information we were looking for. He asked us to go to the regional director whom we have not yet been able to meet, even though we went to the regional directorate three times. We communicated with the institution by email before we filed an official request for information at the quality control office of the regional directorate.

We have also submitted a request for information at the regional directorate of the Water Authority in Khnenifra, and we have sent a recorded letter to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Rural Development, Water and Foresteries and we obtained a receipt that our letter has been delivered.

The numerous calls we have made to every possible relevant entity was part of our effort to exercise our right to obtain the information through all means like registered letters, emails and other smart phone apps, but all our efforts were fruitless until the date of publication of this investigation.

At the end, the complaint has been shelved.

On 26 July, the farmer Abdullah Mahti submitted a complaint against Mohammad Fikrawy to the King’s representative at the Court of First Instance in Khénifra for diverting the stream of Wadi Shbooka to water his farm and thus depriving the complainant of his right to obtain water for his personal and domestic use. He attached a CD to the complaint containing the videos of the hillside dam and the diverted water.

In an interview with us, Mahti explained that the purpose of filing the complaint was to obtain a legal ruling that carries the weight of preventing future violations of water management laws.

IMS’ reader on environment in the MENA region

The pieces published here tell the story of the way the environment has been understood and questioned by our partners in the MENA region.