Egyptian Countryside Development Company sells farmers infertile plots of land

Mohammad Hifzi gave up his life and moved to northern Egypt – 245 kilometres away from his home – to take part in a government backed national investment allowing farmers to reclaim 1.5 million acres of land. Soon, Hifzi realised that the land he was meant to cultivate was infertile due to high salinity of the underground water wells.

By Shaaban Bilal

This investigation was conducted with the support of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ). Following the publication, the Egyptian President directed all concerned authorities to study and explore any current challenges encountering the 1.5 million feddan project carried out by the Egyptian Countryside Development Company, particularly concerning irrigation water supply, quality and infrastructure components especially those related to road pavement, electrical feeding systems and wells development. In addition to localisation of other activities on the company’s land to maximise the benefits of the project. It is worth noting that the investigation documented how the Egyptian government gave tens of applicants, who applied for the “National Project for Reclaiming 1.5 million Feddan (acres of land)”, lands that are unsuitable for agriculture due to the high degree of salinity and the absence of a viable alternative source of irrigation.

Expectations

Reality

Between expectations and reality, here is the story of the failure of the reclamation of the Moghra land.

Mohammad Hifzi gave up his life in Obour region of Cairo and moved to Moghra Oasis, Alamein, Marsa Matruh (northern Egypt), which is 245 kilometers away from his home, to take part in a new government backed national investment allowing farmers to reclaim 1.5 million acres of land for agricultural purposes.

Hifzi learned from official media reports in Egypt that the government was offering land ownership. He approached the New Egyptian Countryside Development Company to learn more about the land and the purchasing conditions to realise his dream of owning agricultural land. “This was my dream that I wanted to realise. The time was right when the national farms project was announced in 2016, which seemed a paradise suitable for agricultural investment due to the resources and capabilities available.”

Hifzi, together with 22 others, applied in October 2019 to reclaim 230 acres split equally among the partners from the New Egyptian Countryside Development Company. He was surprised, however, to learn later that the underground water was not suitable for irrigation, hence, the land was not arable.

In 2016, the new Egyptian Countryside Development Company offered 1.5 million acres (feddan) for reclamation in four main regions: Moghra, West, Minya, Toshka and Old Farafra. The company, which includes representatives from the Ministries of Finance, Agriculture and Housing, managed to attract 13,000 investors.

Hifzi was not alone in complaining about his Moghra land; dozens of other investors working with the New Egyptian Countryside Development Company said it was hard to benefit from the plots of land they have been assigned in Moghra – which are part of 280,000 acres (feddan) that were offered to contractors – due to high salinity of underground water wells.

This violates Article 6 of Law 143/1981, which obliges the government to provide irrigation sources for land reclamation projects.

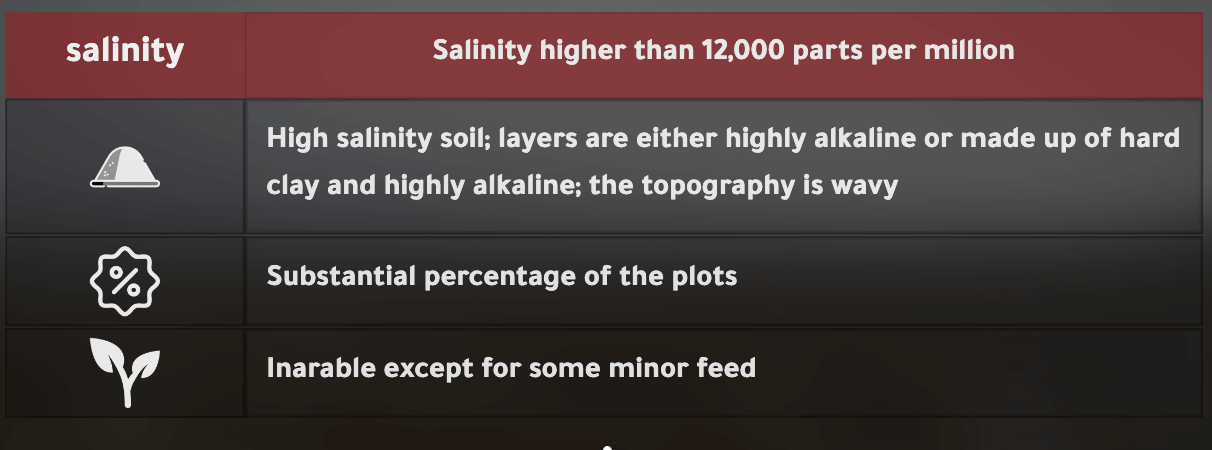

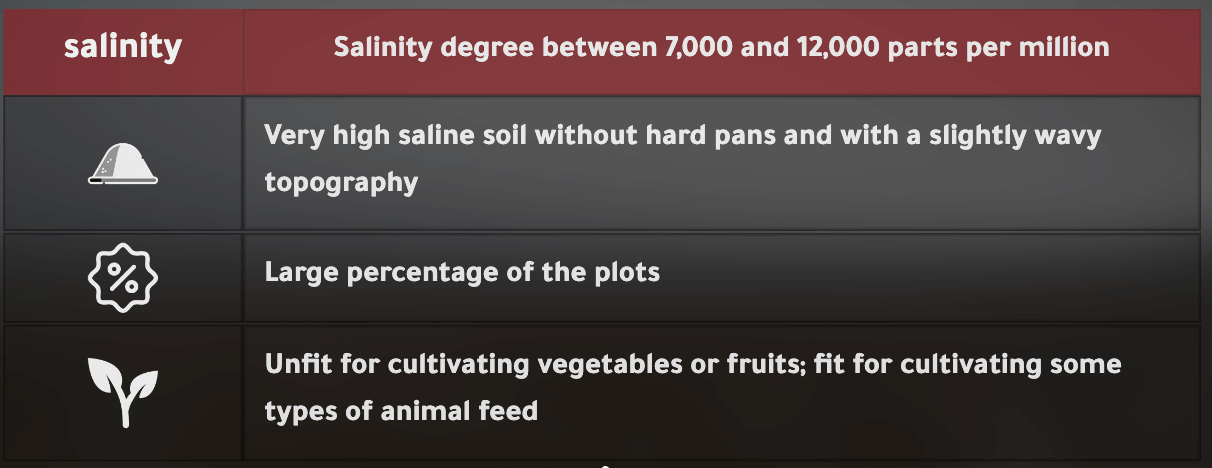

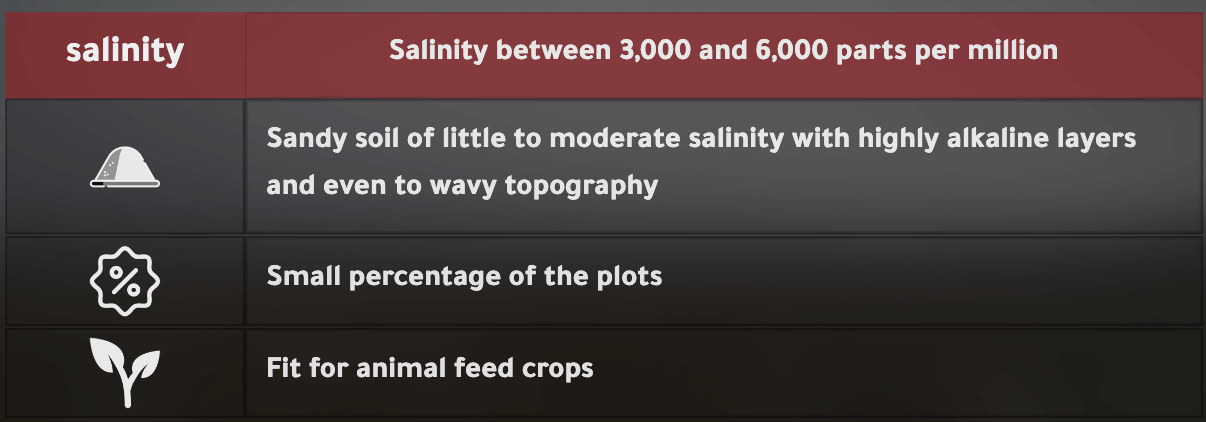

A study by the Ministry of Environmental Resources and Irrigation in March 2021 also found that salinity in most Moghra land ranged between 3,000 and 10,000 parts per million, which renders the land unfit to produce economically feasible crops.

Hifzi and his partners had another underground water well sample analysed with the Egyptian Centre of Excellence for Saline Agriculture. The analysis, carried out in December 2020, showed that salinity in the water of the land assigned to them was 10,400 parts per million.

The report added that 90 out of the 230 acres (feddans) acquired by Hifzi and his partners was completely inarable because its soil is rocky, alkaline and saline.

According to Dr. Hassan Shaer, director of the Egyptian Centre of Excellence for Saline Agriculture, which is part of the Desert Research Centre, salinity of more than 7,000 parts per million renders any land unfit for producing anything other than some sorts of animal feed.

High salinity did not stop Hifzi from trying. He cultivated many crops, including onions, super Mombasa (animal feed) and alfalfa, but all crops ended drying up due to high salinity, and Hifzi suffered huge losses.

Hifzi filed a complaint against the New Egyptian Countryside Development Company (number 4553), in which he called for a solution for the water salinity and asked for damage compensation towards his 90 acres. He got no response; on the contrary, the company asked him to cultivate the land and commit to paying on time the instalments as set by the contract.

Article 17 of Law 143/1981, which deals with desert land, and the law’s Executive Regulations 198/1982, stipulate that anyone who buys land with access to an irrigation source, as governed by this legislation, with the intention to reclaim it and cultivate it, is given a five-year deadline to complete the task starting from the date when the irrigation source is made available.

High salinity

Since many contractors with the company faced the high salinity problem, they formed the Moghra Alliance and reached out to the Egyptian Centre of Excellence for Saline Agriculture to study the composition of the soil and water resources available in 20 land plots (each is 238 acres and the total is 4,760).

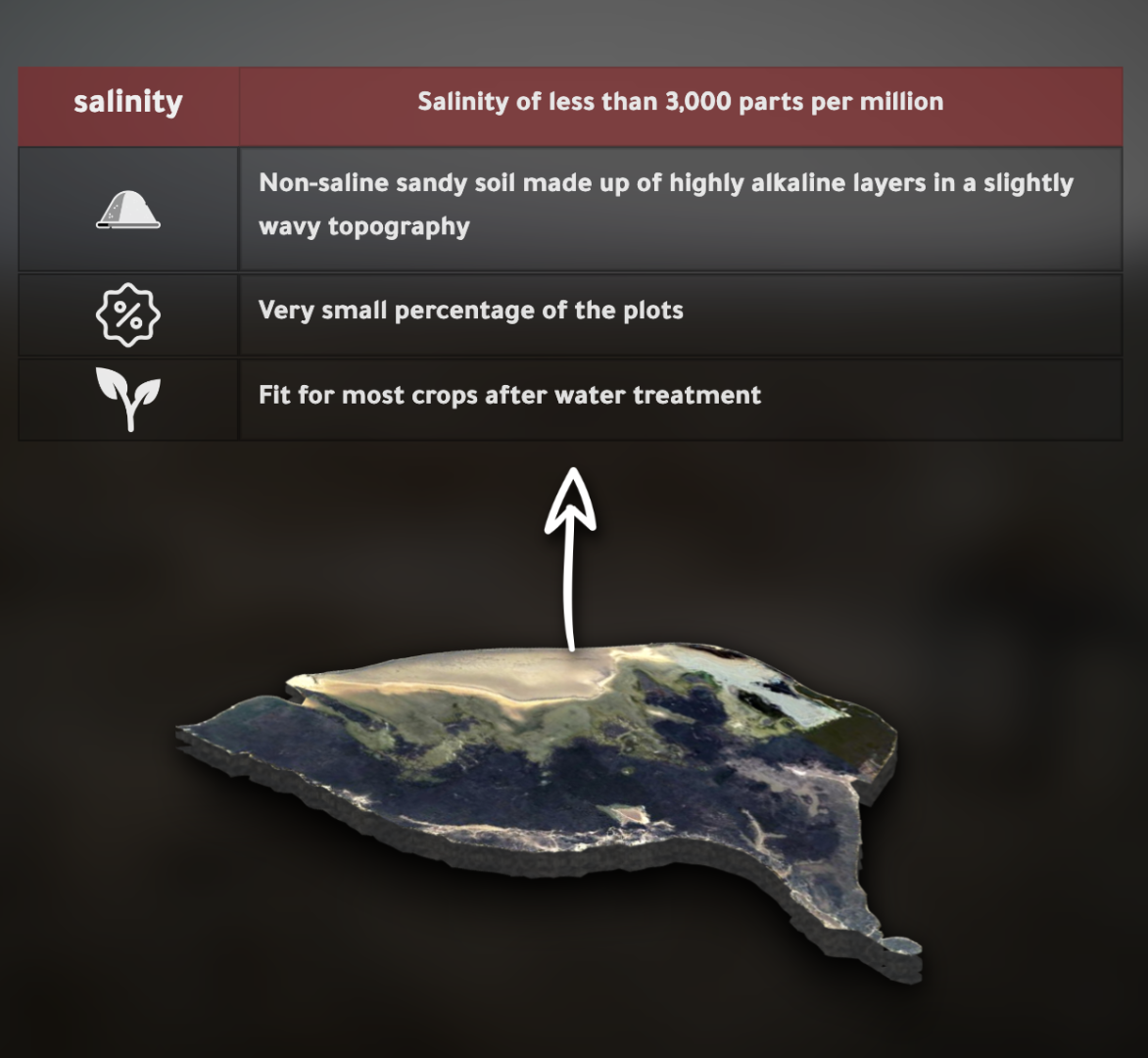

The centre’s study, issued in the alliance’s name, found four types of soil in the area:

Dr. Hassan Shaer, director of the Egyptian Centre of Excellence for Saline Agriculture, which is part of the Ministry of Agriculture’s Desert Research Centre, says soil characteristics in Moghra vary greatly even within the same acre. These characteristics make land reclamation hard, as most of the land is made of infertile sandy loam and cannot be cultivated, he adds.

Dr. Shaer says that upon a request by the government, the Desert Research Centre is carrying out an assessment of the salinity of underground water and soil in the Moghra region. The project, he adds, was not founded on scientific grounds from the beginning as the company did not carry out adequate research from qualified entities to lay down the right technical foundations for reclaiming these vast plots of land as part of one of the most important agricultural projects in the country.

Two conflicting reports

Being a resident of Faqus, a city in Sharqia Governorate that is more than 170 kilometres away from Moghra, did not stop Mohammad Hasaballah from taking up a contract with the New Egyptian Countryside Development Company to reclaim Plot 119 in 2018.

Unlike Hifzi, Hasaballah got his land with an underground water well, but the company “provided two contradicting reports about the well water levels of salinity,” he says.

When the contract was signed in August 2018, he got a report saying that the salinity level was at 2,150 parts per million. Hence, he and his partners agreed to sign the plot’s contract as such salinity could be treated with modern technology. But once they were handed the plot in October 2018, the company provided another report, claiming that the soil’s salinity was at 4,000 parts per million.

A water sample he had tested at the Agricultural Research Centre – a government run institution governed by the Ministry of Agriculture – showed in July 2021 that salinity was at 10,560 parts per million.

Dr. Mohammad Wasif, a professor of land maintenance at the Agricultural Research Centre, says that at such salinity levels, it is impossible to cultivate economically feasible vegetables and fruits because such crops cannot grow in such salinity.

Wasif argues that due to the current salinity levels, Moghra plots are suited mostly for animal farming and farms of certain kinds of feed, such as beet fodder, which can grow at 6,000 parts per million of salinity.

In a memo, Hasaballah and his partners asked the New Egyptian Countryside Development Company to take the necessary measures. In the memo, they said that they had cultivated several crops, including sunflower, watermelon, wheat, barley and super Mombasa. More recently, they cultivated olives in 120 acres. All crops turned out to be poor due to salinity, and the partners lost four million Egyptian pounds (approximately $260,000) in two years.

Like Hifzi, Hasaballah and his partners did not get any response from the company.

Infertile lands for agriculture.

Legal violation

Failure by the New Egyptian Countryside Development Company to respond to complaints by those affected forced them to sue the company, the Minister of Agriculture, and the chairman of the board of the General Authority for Construction and Agricultural Development Projects.

The lawsuits, of which we obtained copies, require that the company provide fresh water suitable for irrigation and agriculture and a five-year grace period starting from the date of making water available, with the provision of this resource to allow the beneficiaries the time to cultivate crops before settling the remaining instalments.

In his lawsuits, Issawi relied on reports by official research centres, including those issued by the Centre of Agricultural Research and the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation, confirming the land´s salinity.

Issawi says the New Egyptian Countryside Development Company did not set in the contracts the salinity of the Moghra lands, stretching on 286,000 acres, arguing that this should have been done from the beginning.

We confirmed this after reviewing the contracts.

Rejection of the proposed solution

In March 2021, the founders of three companies who invested with the New Egyptian Countryside Development Company filed a complaint at the Prime Minister’s office (number 17457). They asked for an authorisation to transport fresh water from an agricultural wastewater treatment and desalination plant being constructed south of the El-Hamam area all the way to Moghra, after their attempts to treat the underground water available in their plots to a degree suitable for agriculture had failed.

The head of horizontal expansion and projects at the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation declined, claiming that the agricultural wastewater to be treated at the plant is earmarked for use in specific regions, adding that no extra water would be available for Moghra.

Losing family and money

When the New Egyptian Countryside Development project was launched (by the government) in 2016, Shawky Mujahid, of El-Beheira Governorate (200 kilometres away from Moghra), took out a contract with the New Egyptian Countryside Development Company. He thought he would have another successful land reclamation project, similar to the one he carried out with the Project of Al Kherrijeen. However, disappointment followed after his parting with the down payment and allocation of his plot.

Mujahid, the legal representatives of plots 589 and 590 in Moghra, says he and his other family members discovered that salinity at his plots ranged between 3,000 and 10,000 parts per million, according to a report by the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation. Hence, the plots were unsuitable for any economically feasible crops, and he stopped cultivating the land.

On 20 May, the New Egyptian Countryside Development Company sent him an official warning threatening to take legal actions against him and to withdraw the plots if he did not license the plots’ underground water well and present an urgent plan to reclaim and cultivate at least 60 percent of the area within a 36-month deadline starting from the date of his plots allocation.

This investment has spoiled Shawky’s relations with his brothers and some other family members after they accused him of dragging them into buying useless land plots at EGP 20,000 per acre (approximately $1,300), whose economic returns are not commensurate with the cost.

Mujahid stopped talking to his brothers because of this failed project.

Hifzi, Hasaballah, Mujahid and dozens of other investors in Moghra are still waiting for a solution: either the transportation of fresh irrigation water to their plots or a judicial verdict granting them damages.

IMS’ reader on environment in the MENA region

The pieces published here tell the story of the way the environment has been understood and questioned by our partners in the MENA region.