Palestine’s contaminated vegetables: present on our tables, absent regulations

In 2022, two years after the publication of the investigation, the State Audit and Administrative Control Bureau, which is the highest supervisory authority in Palestine, issued a report in August on the poor control procedures applied on the use of pesticide in the West Bank, where the results confirmed the conclusions of the investigation. The investigation revealed the presence of agricultural pesticide residue in high proportions in vegetables offered to the Palestinian consumer in violation of the specifications and standards of the Codex Alimentarius issued by the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization, harming the consumer’s health amid weak oversight and conflict of powers between the Ministries of Agriculture and Health.

The bright, colourful vegetables on Palestinian markets stalls conceal secrets that only laboratory equipment can uncover.

The secrets buried in the two main crops on the Palestinian table, tomatoes and bell peppers, began to unravel in 2017. That year, 20 samples of both crops were taken from various West Bank cities for examination at the Laboratory Testing Centre at Birzeit University. At the time, the regulatory bodies had promised to reform the agricultural pesticides sector and to develop means to conduct checks periodically.

This investigation was conducted with the support of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ). Founded in 2005, ARIJ has helped journalists adapt to changing technology in a constantly shifting political journalism landscape – in a challenging environment of press freedom and access to information.

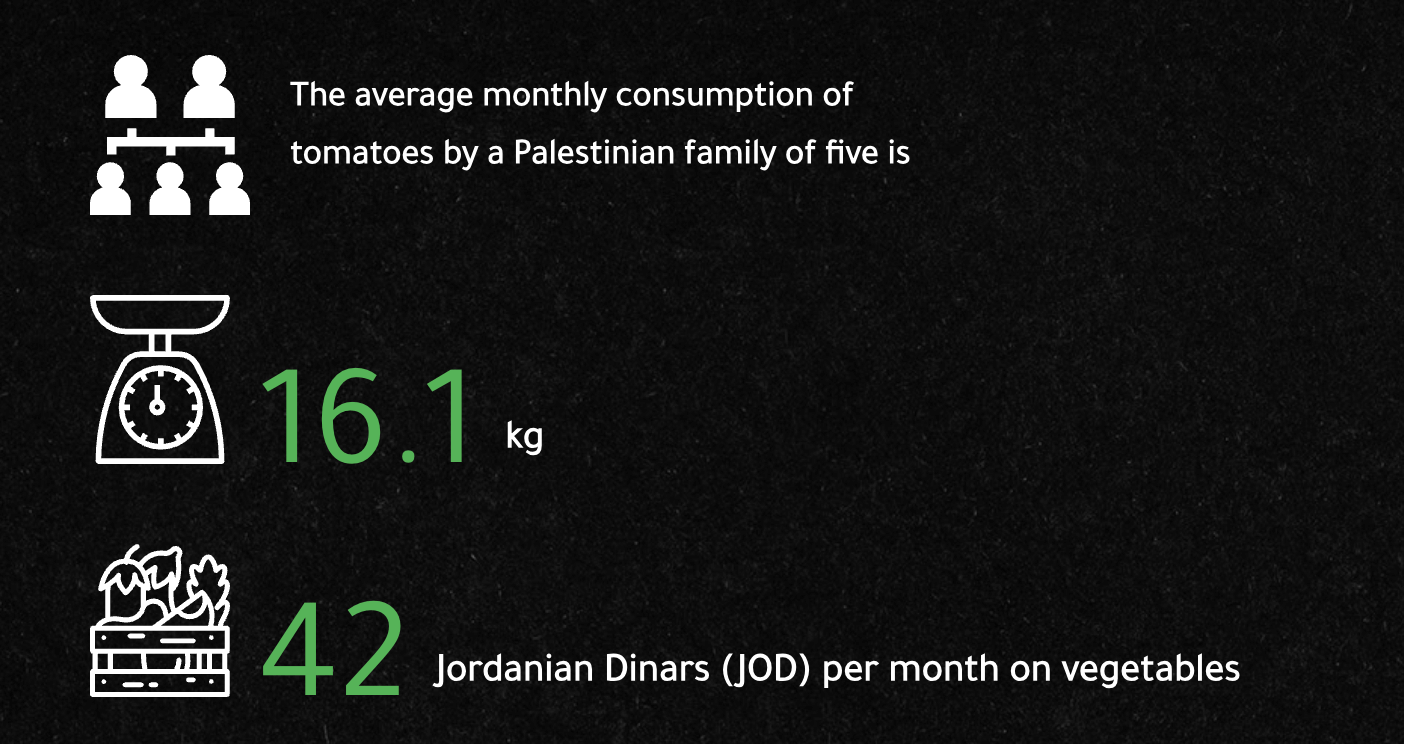

According to a survey conducted by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics in 2011.

Three years later, nothing has really changed; no blueprint for verification and random use of pesticides continues. To confirm this, in early 2020, ARIJ reporter conducted another series of tests on eight samples of tomatoes and bell peppers from the northern, central and southern parts of the West Bank.

Test results showed no improvement in regulation. In fact, the situation had worsened. Over the course of three years, this investigation revealed that vegetables being sold to Palestinian consumers contained high levels of agricultural pesticide residues. These levels violate the specifications and standards of Codex Alimentarius, issued by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FOA) and the World Health Organization (WHO). They also harm consumer health amid weak oversight and conflicts between the Ministries of Agriculture and Health.

Palestine’s vegetable basket: free from any oversight

One morning of December 2017, ARIJ’s reporter travelled from Ramallah to the Palestinian side of the Jordan Valley – also known as “Palestine’s vegetable basket” as it produces 60 percent of the country’s total vegetables in the market. The warmer weather, fertile soil and abundant water resources due to the valley’s sitting on top of the country’s main water basin, means that the land can be cultivated throughout the year.

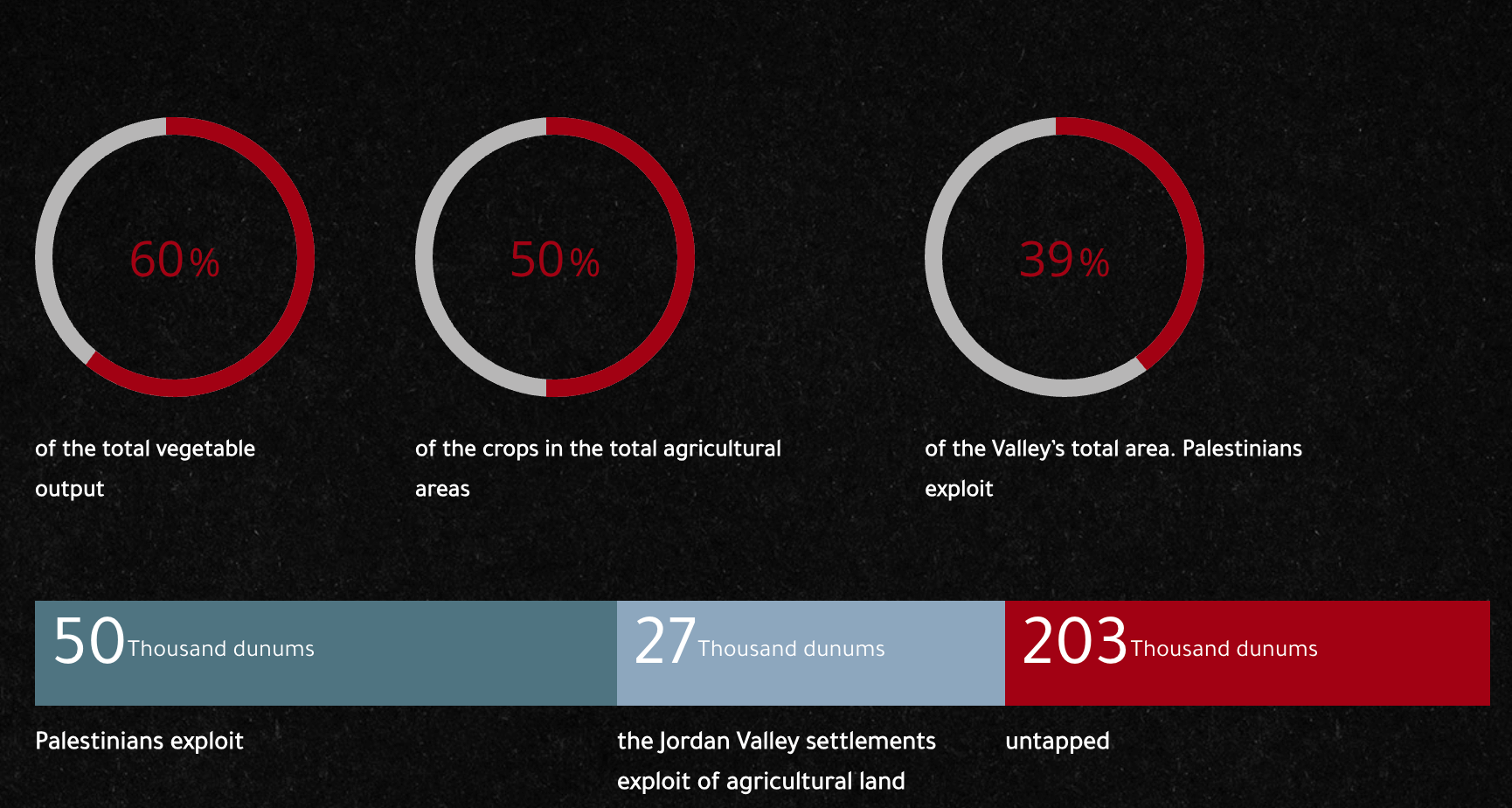

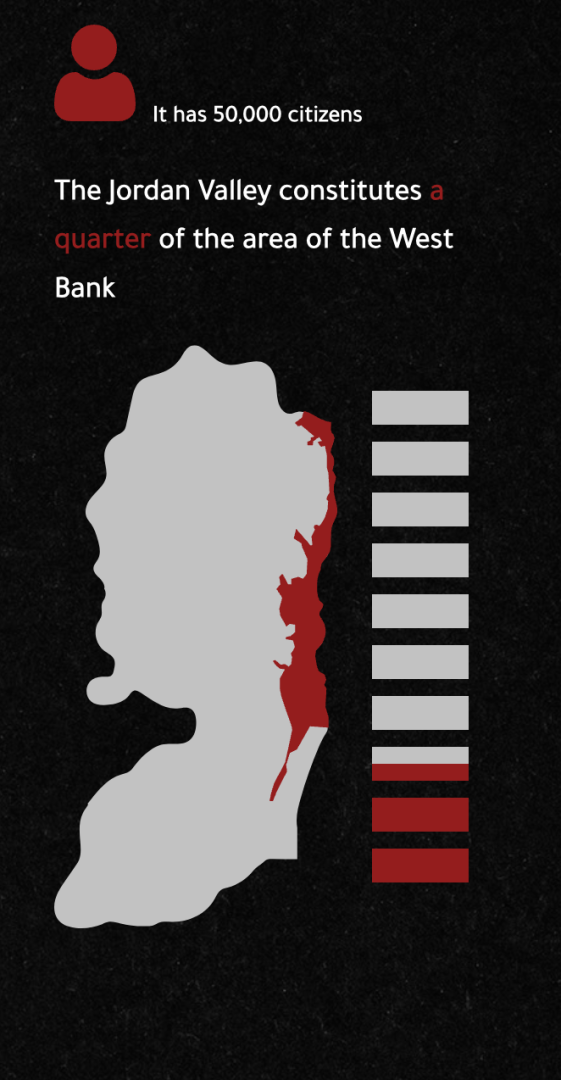

The Jordan Valley forms approximately a quarter of the West Bank. It is inhabited by 50,000 citizens and produces 50 percent of the crops of Palestine and 60 percent of the total vegetable output in the country. The area has 280,000 dunums of arable land, that is, 38.8 percent of the Valley’s total area. Palestinians exploit 50,000 dunums, while the Jordan Valley Israeli settlements exploit 27,000 dunums of agricultural land.

Source: The Palestinian National Information Centre.

Muhammad Abu Al-Sheikh, 52, is a farmer from the village of Bardala. He was preparing to harvest crops from his land. He took us on a tour of his agricultural lands in his car to see the reality of how pesticides are used.

“I’m telling you, never in my life have I seen anyone from the Ministry of Agriculture on my land, not to provide any kind of guidance, nor to take samples for examination. Honestly… I have never seen them. I know that the Ministry of Agriculture must come to inspect the farm and monitor pesticides and their use. If the Ministry, which is the concerned party, does not care, how am I supposed to bother as a farmer? They should just take samples and check them. If there is anything wrong with them, they can hold me accountable,” he told ARIJ’s reporter.

Samih Khdeirat, a farmer in his 40s, confirmed this too. Standing in the middle of his land planted with bell peppers, Samih said: “No one from the Ministry of Agriculture has come for the purpose of inspection or guidance. Farmers use pesticides as they wish, and they mainly rely on their own personal experiences. For example, if we spray a pesticide that does not eliminate a specific disease, we increase the concentration of the pesticide to take care of it. “

According to farmers’ reports, regulation of the Palestinian vegetable basket sector is non-existent. This seems also to be the case after the crops leave the fields and head to the market, as asserted by vendors in the central vegetable markets in northern and central parts of the West Bank.

“No one is verifying. Never before have the Ministry of Agriculture or any other party taken samples for examination purposes,” one vendor told ARIJ.

The majority of vendors we interviewed agreed that they are not responsible for the presence of any harmful levels of chemical residues in their fruits and vegetables. They hold the Ministry of Agriculture responsible.

One of the vendors located in Al-Fara’a Market near the city of Tubas told ARIJ that “the Ministry of Agriculture is the one that should examine and guide farmers, you see. Cancer cases that are happening are all due to pesticides.”

Another vendor travelled from Hizma, north of Jerusalem, to the Beita central market, south of Nablus, to buy vegetables for his shop. He did not hesitate also in accusing the Ministry of Agriculture of negligence, and hastened to absolve himself of the responsibility to identify the presence of any toxic substances in the crops that he sells to his customers.

“The Ministry of Agriculture is responsible, of course. The Ministry must follow up and monitor farmers, what they plant and what pesticides they use to grow their vegetables. I am a shop owner; I am not the government or the Ministry to be able to follow up on this matter,” he said.

Other vendors in the central market of Al-Bireh in the centre of Ramallah have similar views in holding the Ministry of Agriculture responsible. One even expressed surprise when asked about the responsible party.

“Of course, there is no question about the issue: The Ministry of Agriculture must monitor these matters. I am a vendor! What do I know?” he said.

A colleague standing behind him at a nearby tomato stall jumped into the conversation and summed up the matter: “Our role as vendors is to bring the goods to sell. I am neither a farmer, nor the Minister of Agriculture, nor an agricultural engineer. I am a vendor who sells vegetables, and this is how I make my daily living. If I were an engineer, I would gladly take responsibility.”

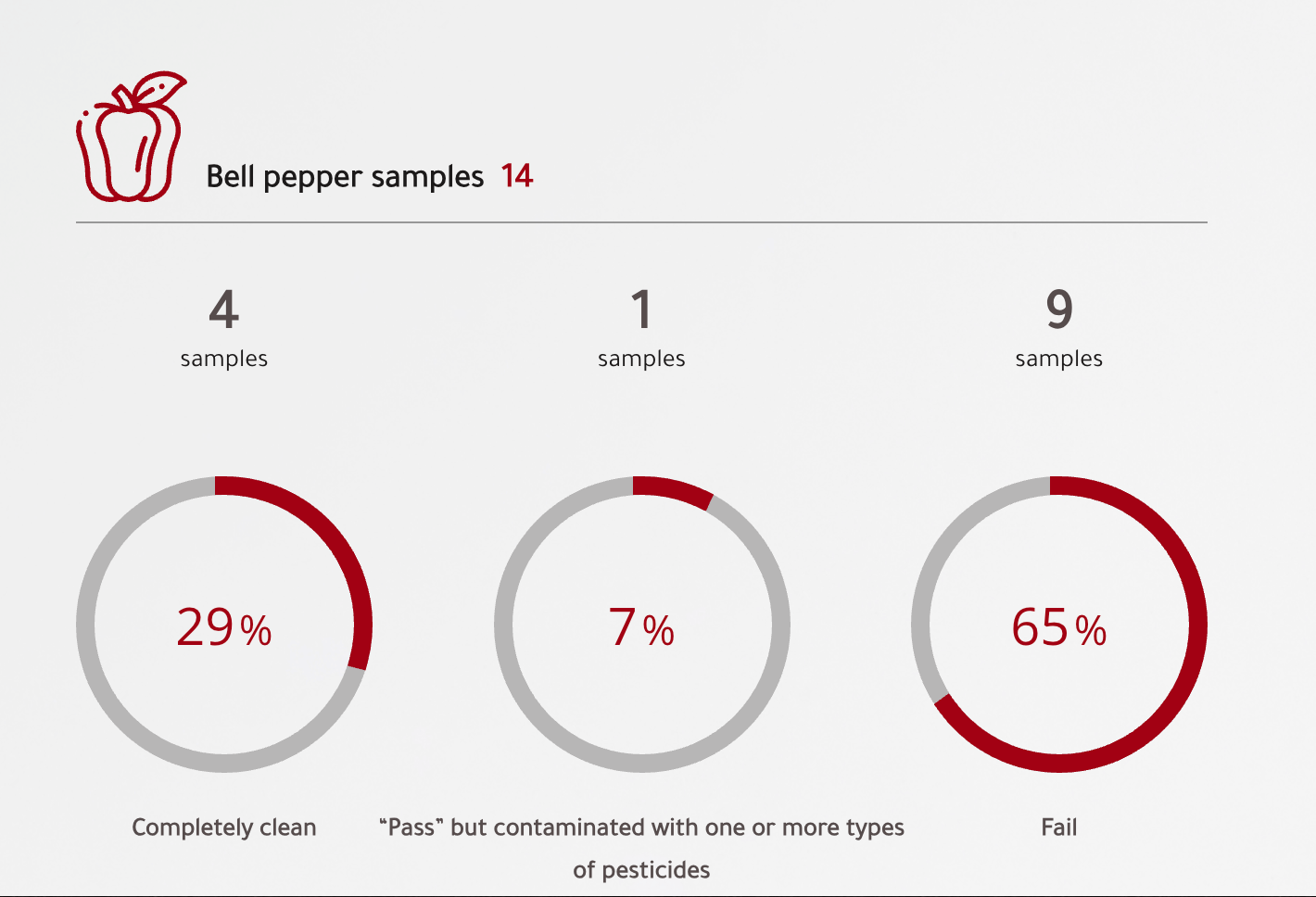

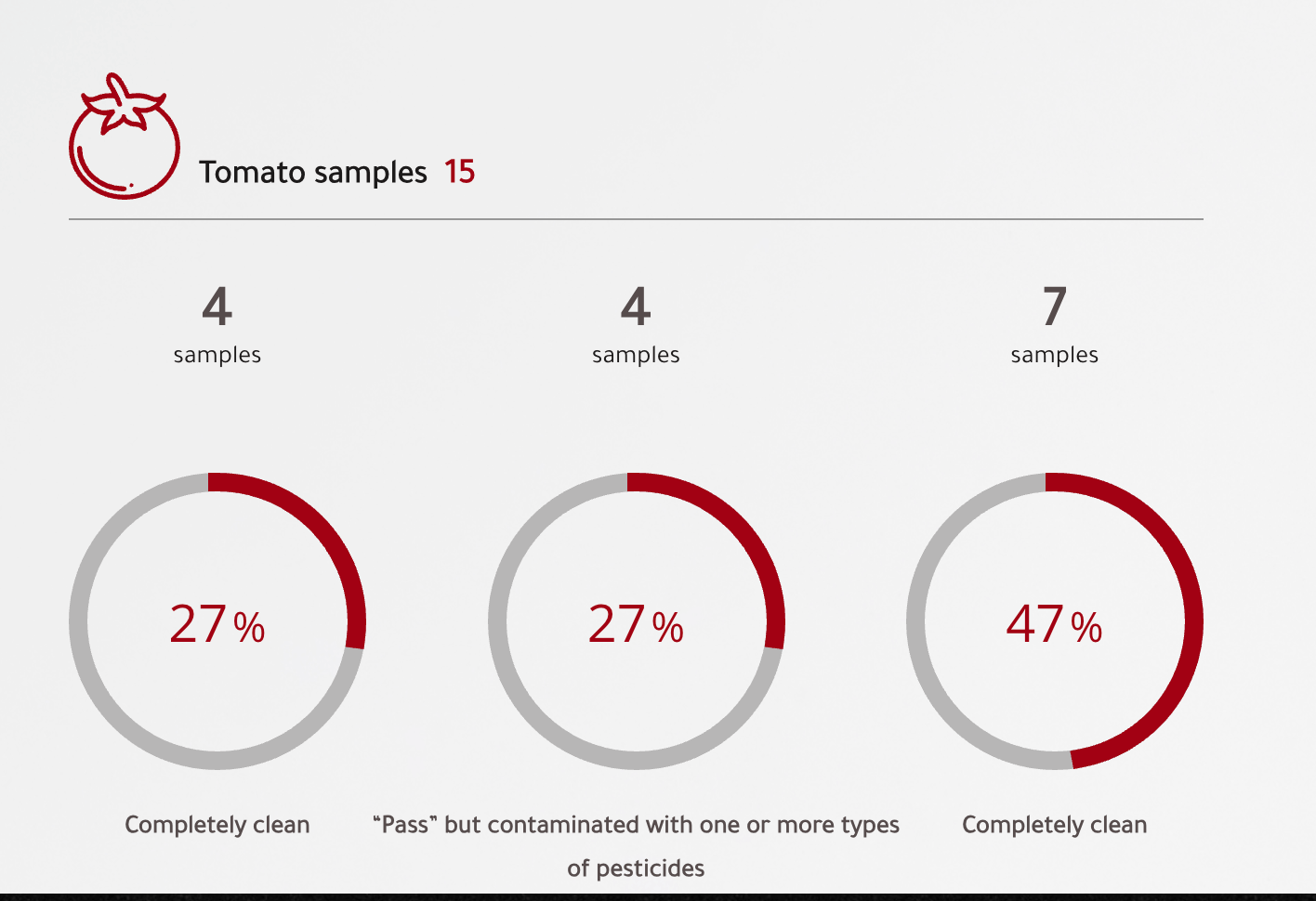

Over 72.4 percent of examined samples were contaminated

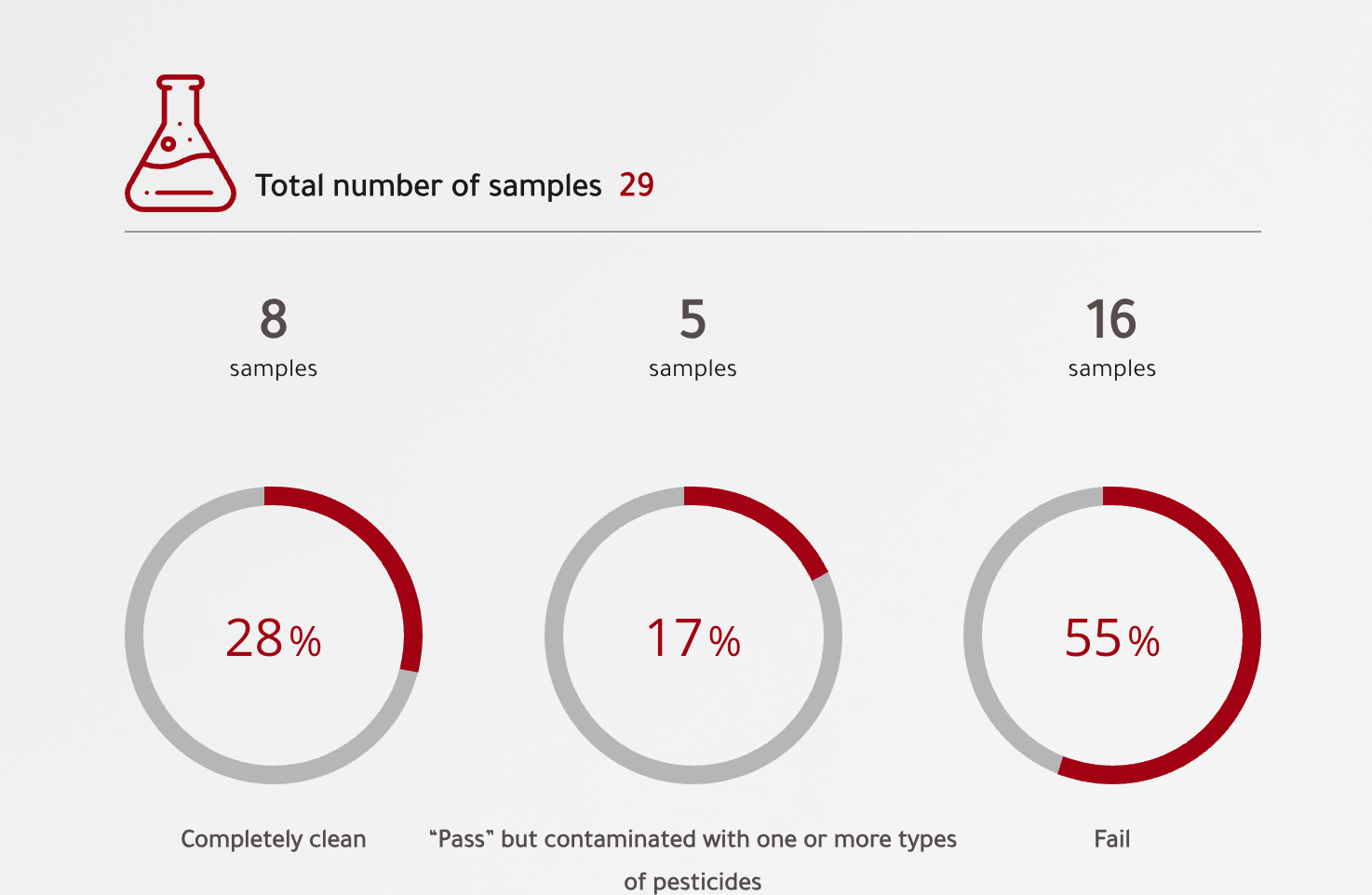

The laboratory results of 29 samples of tomatoes and bell peppers that were taken from various cities in the West Bank showed that 72.4 percent showed levels of contamination, meaning they contained one or more types of pesticide residues. The results also revealed that 55.1 percent of the samples included precipitates, meaning they contained levels of residues of chemical pesticides that are higher than the so-called maximum limit permitted internationally for human consumption by the WHO.

Only 17.2 percent, or five of the total samples provided for testing, showed that their pesticides residues levels were less than the permitted limits. The samples totally free from pesticides did not exceed 27.5 percent of the samples, that is eight samples.

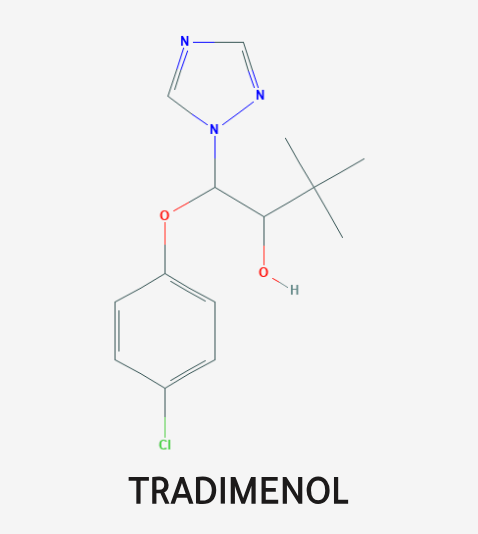

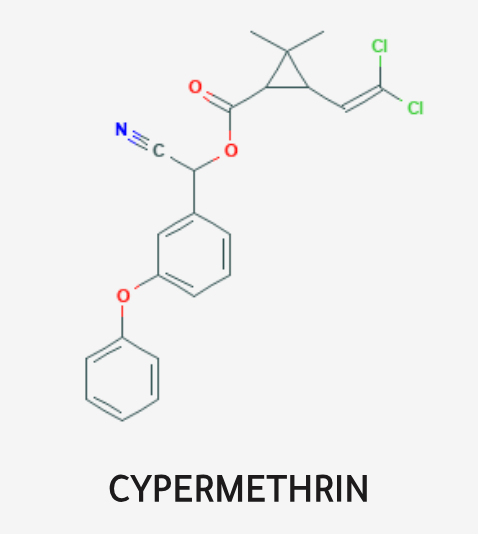

The tests were carried out over two stages. The first was done in late 2017 on 21 samples, and the second was conducted in early 2020 and covered eight more samples. The aim was to give the regulatory authorities an opportunity to rectify the situation and tighten control over the use of pesticides. However, the results did not show any changes. On the contrary, things got worse as new pesticides originally banned from use in Palestine made their way back to farmers’ agricultural fields.

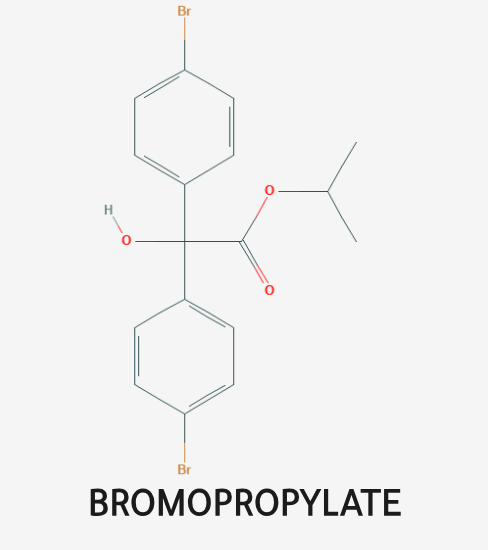

Exposure to bromopropylate is harmful to the respiratory system.

The toxic substance has been proved to affect the body’s digestive system, eyes and skin.

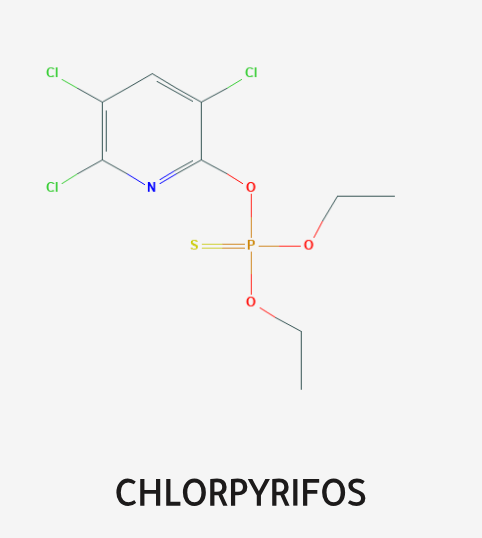

Short-term symptoms of low-dose exposure include headache, agitation, inability to concentrate, weakness, fatigue, nausea, diarrhoea and blurred vision. High doses can lead to respiratory paralysis and death. Chlorpyrifos is associated with a number of serious long-term health effects including developmental disorders, increased likelihood of having children with autism spectrum disorder, endocrine disorder, lung and prostate cancer.

The Cancer Assessment Review Committee (CARC) has identified this pesticide as a carcinogen.

Excessive ingestion through the skin and mouth leads to death and is a source of concern to neuroscientists, as daily exposure in small amounts induces neurodegeneration. It also affects the activity of sperm glands in males.

The US Environmental Protection Agency has classified it as a potentially carcinogenic substance

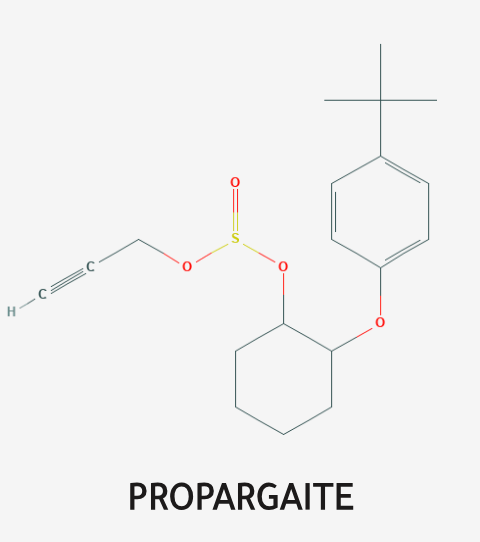

Propargaite was banned in the US as a carcinogen, according to the Environment Agency, after its effects were tested on animals. Its results showed that it is carcinogenic, increases intestinal tumours and causes human dermatitis, cancer and reproductive toxicity.

Damage caused by insecticides

George Karzam is a researcher and environmental expert who also heads the Studies Unit at the MA’AN Development Centre. Karzam says that the percentage of samples free from insecticide residues is very low.

“The most dangerous thing that these results have revealed is the detection of some domestically and internationally banned insecticides, as those are still in use here. For example, the insecticide known as ‘Endosulfan Thionex’ has been banned globally for many years, and residues of this pesticide have been detected in the samples. What’s more, is that all the contaminated samples in particular contain a mixture of compounds, meaning that they contain more than one compound, in twos, threes or fours with the exception of one sample. This is extremely dangerous because it is clear that the motive for making the mixture of the chemical compounds and the active pesticide ingredients is to increase the levels of their toxicity,” he said.

A chaotic pesticide market

Research was done on the methodologies followed in Palestine to determine permissible or prohibited pesticides usage. The chaos and the lack of clear scientific methodologies guiding the farmer’s application of pesticides was obvious immediately. For example, some banned types of pesticides are featured again on the official lists adopted by the government. Take the insecticide “MANCOZEB”, which Resolution No. 14 of 2011 was issued by the Minister of Agriculture, to ban it and a group of pesticides going by the same scientific name and its related active ingredients.

According to the environmental expert, Mr Karzam, the ban should be on the active ingredients and not on the brand names. For example, MANCOZEB was banned under its various brand names. However, this pesticide group became permissible after 2011 despite the official ban. It appears on the list of agricultural pesticides permitted for use in the Palestinian Authority regions issued in 2013-2014, as well as on the 2016-2017 list.

Likewise, Chlorfenapyr, an insecticide also known by its trade name “Berat”, was banned according to the same 2011 resolution. This pesticide featured again as safe to use on the official 2016-2017 list.

Karzam told ARIJ, that “sometimes the use of pesticides under their brand names could have been prohibited, but the use of its same active ingredients could be still permitted. This is an insult to people’s intelligence. The principal action should be to define the scientific active ingredients and decide to ban or allow the use of those pesticides.”

The environmental researcher points out that the issue of a maximum permissible limit is misleading, and in fact is “a big lie”, because it is neither controllable nor measurable by ordinary consumers. The maximum permissible limit is for a specific pesticide in a certain type of vegetable whereas “our intake and daily consumption of such types of vegetables and fruits is varied. We consume several of these tomatoes or fruits at once. So how will citizens measure their pesticidal maximum limits at home?”

Ministries blame each other

No one would acknowledge responsibility for inspecting agricultural crops in fields and markets, as the ministries of Agriculture and Health refuse to own up to it. The Ministry of Agriculture has only 13 inspectors in the West Bank. Their role is limited to monitoring pesticide stores and to following up on their licensing and import processes, but has nothing to do with monitoring agricultural goods after they leave the fields.

This means that the vegetables and fruits offered to Palestinian consumers are not subjected to any kind of checks. Instead, they are taken from the fields to the market and then to the consumer without any health and safety control measures to insure they are safe to consume, and this exposes people to diseases that manifest themselves in the long run.

Spokesperson and Director of the Pesticides Department at the Ministry of Agriculture, Abdel-Jawad Sultan, asserts that the Ministry’s task ends in the fields. He believes that the role of inspecting and ensuring that agricultural crops are free of pesticide residues falls at the door of the Ministry of Health.

“Vegetables are agricultural goods, and our responsibility ends after the crop leaves the farm. Herein lies the role of the Ministry of Health, which has the task of inspection since the powers to inspect markets are within its authorities,” he told ARIJ.

But the Ministry of Health believes that the responsibility of examining residue in produce must fall on to the Ministry of Agriculture.

Ibrahim Attia, who passed away in March 2020, was the Director of Environmental Health at the Ministry. He stressed that the responsibility of his Ministry in this area is limited to agricultural products that move to the stages of processing and packaging. Examples include thyme after it is milled and ready to be sold as finished product and tomatoes once they are cooked and turned into tomato paste.

Due to its competence and responsibility for the pesticide sector, Attia called on the Ministry of Agriculture to tighten its control over farmers and how they apply the pesticides. He also called on the Ministry to provide farmers with the necessary guidance by continuing to take random samples from markets and fields for testing.

The Ministry of National Economy claim that the Ministry of Agriculture is in charge

While accusations kept flying between the ministries of Agriculture and Health, we looked for guidance from the Consumer Protection General Administration at the Ministry of National Economy to verify the role it played, if any, in checking the safety of vegetables and fruits as produce offered to consumers.

The Ministry’s assessment pointed to the failure of the status quo as it does not achieve market discipline in the agricultural production sector due to the lack of a clear mandate for the responsibility of each ministry that prevents any overlaps or loopholes .

According to the Director of Consumer Protection, Ibrahim Al-Qadi, there is a Palestinian strategy for food safety that was prepared by the ministries of Health, Agriculture and Economy to control animal and agricultural products.

It was agreed that the responsibility of the Ministry of Agriculture extends from the farm to the market – that is, from the farmer to the consumer. According to Al-Qadi, what is missing now is reaching an agreement between the ministries of Agriculture and Health by which the Ministry of Agriculture takes samples and sends them to the laboratories of the Ministry of Health for examination. But 30 months since his declaration, the agreement between the two ministries has yet to be signed. For nearly three years now the state of pesticide use remains the same and is still out of control.

Expert opinion: pesticide residues lead to diseases in the long term

Dr. Aqil Abu-Qare’, a researcher in the field of pesticides, was horrified by the chemical pollutants found in the tomatoes and bell peppers examined, especially that some contain pesticides banned in Palestine. What is more worrying is the presence of more than one pesticide in each sample, which leads to an increase in toxicity.

Abu-Qare’ holds a PhD in chemical pesticides from the UK, and warns against mixing pesticides and spraying them on vegetables.

“There are short-term harms such as immediate toxicity as a result of which symptoms such as nausea appear. If the concentration is high, it may lead to paralysis or to death if the sprayed quantity consumed was huge.

“This would explain the increase in the incidence of chronic diseases in Palestine. The consequences of the exposure of the human body to small quantities begin to appear over time, and these have great repercussions. The most significant of these is cancer, which is the second cause of death in Palestine. This is in addition to diseases impacting the endocrine and respiratory systems as well as the pesticides’ special effects on pregnant women. The direct effects of these diseases do not appear immediately but after several years of exposure to the residues; therefore, their causes cannot be precisely determined,” he told ARIJ.

“Pesticides are among the leading causes of death due to self-poisoning, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

– The World Health Organization

“Since pesticides are toxic by nature and spread slowly in the environment, their production, distribution and use require tight regulation and control. Also necessary is the regular monitoring of pesticide residues in foods and in the environment.

“Handling large amounts of pesticides may cause severe poisoning or long-term health effects, including cancers and adverse effects on reproduction.”

The results of the laboratory tests reveal a state of chaos in the use of pesticides some of which are prohibited in Palestine and globally. Chaos and the failure to perform the assigned supervisory roles leave the consumer exposed to slow death due to toxins that enter the body and accumulate over the years until their effects appear in the form of various diseases.

IMS’ reader on environment in the MENA region

The pieces published here tell the story of the way the environment has been understood and questioned by our partners in the MENA region.