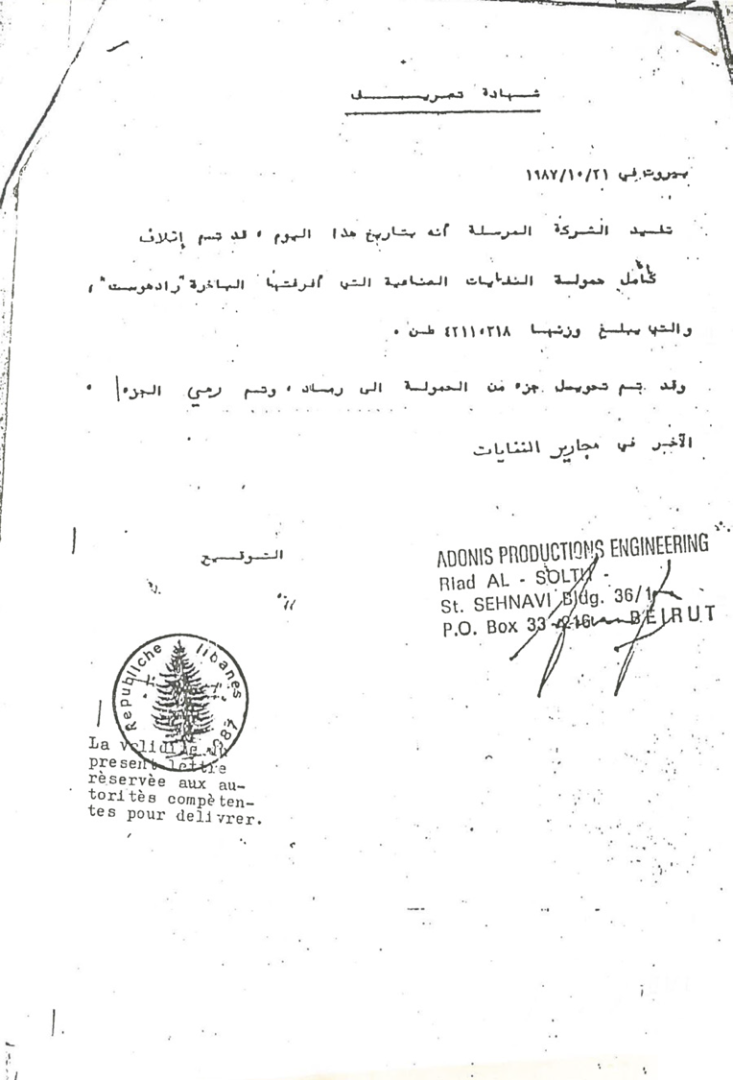

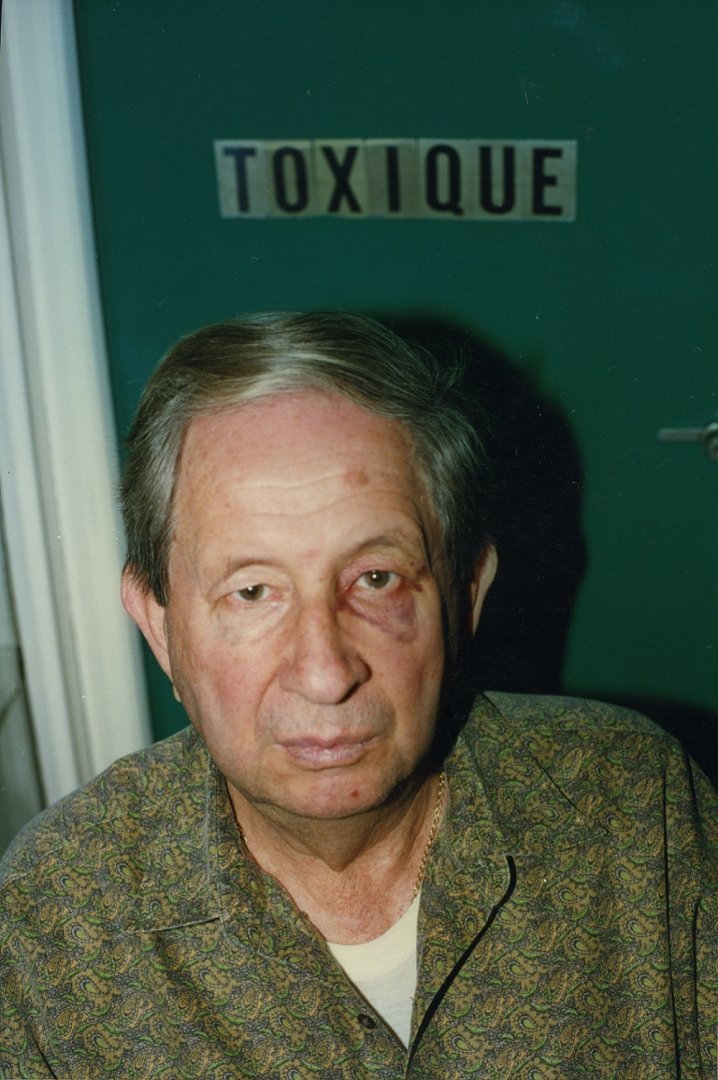

A composite of a forged document claiming the successful incineration of the toxic waste, the Radhost motorship, and the toxic barrels. (Photos © ShipSpotting/Wolfgang Kramer & © Dr. Pierre Malychef from Lab of False Witnesses for Ecotoxicological Research and Communication)

The “ecological time bombs” unloaded at the Beirut Port decades ago

In 2013, tonnes of ammonium nitrate were stored at the Beirut Port, where seven years later it would explode, destroying large parts of the capital. However, this was not the first time Lebanese authorities had welcomed dangerous cargo. In this two-part investigation, the Public Source tell the story of how 35 years ago, over 2,000 tonnes of industrial toxic waste from Italy was dumped in Lebanon – and how it remains in the country today.

By now, we all know the story: how the mysterious, Moldovan-flagged cargo ship Rhosus unloaded 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate at the Port of Beirut in 2013. How on 4 August 2020, an unknown quantity of it exploded, killing at least 259 people and displacing 300,000. How the entire world reacted with shock: how could the Lebanese authorities leave such a dangerous compound unsecured for over half a decade in a run-down port warehouse?

But this wasn’t the first time Lebanese authorities welcomed a life-threatening cargo from abroad into the port – and then abandoned it where it would do the most harm. Thirty-five years ago, another “poison ship” brought another deadly payload into Beirut: 2,000-plus tonnes of blue plastic barrels, packed full of industrial toxic waste from Italy, including explosives and toxic compounds, like PCBs and dioxins, that were banned in Italy and Europe.

This article was originally published 4 August 2022 by The Public Source. The Public Source is a Beirut-based independent media organisation dedicated to uncompromising journalism and critical commentary from the left. The Public Source writes deeply and critically on vital issues from local perspectives, in the service of public interest and in solidarity with Global South publics.

Two years ago, the ammonium nitrate exploded, making its deadly potential clear in an instant. But much of Italy’s toxic shipment remains in Lebanon to this day. For 35 years – over a third of a century – its poisons have leached into watersheds, food sources and people’s bodies, creating an unknown number of slow-motion explosions that environmental watchdog Greenpeace described as “ecological time bombs in Lebanon’s soils and waters.”

Today, two years after the Beirut port explosion, Lebanon has yet to charge a single top official with any wrongdoing. Thousands of families who lost homes or loved ones are still waiting for answers to the most basic of questions: Who was behind this major crime? Will the perpetrators ever be held accountable? Will its victims, or their families, ever see any form of restitution?

Most of all: What, if anything, will the government do to prevent these kinds of crimes from happening again? And again?

To answer these questions, The Public Source retraced the journey of Italy’s infamous poison barrels – and the massive cover-up that followed. We interviewed environmental experts and people who grew up next to illicit dumping grounds. We tracked down the sole survivor of the government-appointed scientists who investigated the barrels at the time. We examined construction reports, public-private documents, testimony from court-appointed experts, a transcript of Italian police interrogation of one of the hidden culprits and a host of intra-governmental documents that our reporters unearthed.

For 35 years, Lebanese authorities have tried to hide sites where toxic barrels are buried, discredited scientific investigations, blocked judicial attempts to prosecute perpetrators and shielded the men who profited from the crime.

Our investigation found that Lebanese authorities are still trying to hide the barrels, and what happened to them, to this day. For three and a half decades, they have tried to hide sites where toxic barrels are buried, discredited scientific investigations, blocked judicial attempts to prosecute perpetrators and shielded the men who profited from the crime.

“The case of the toxic waste is an example of how the Lebanese state and judiciary handle anything that poses a serious danger to the Lebanese people’s lives,” researcher Joelle Boutros, who previously reported on the story, told The Public Source. “Today, we still have no idea how much of [the toxic waste] remains, or where it is located. What actually ended up happening was that the experts who discovered the barrels and brought the issue to the public were deemed the threat. Because they allegedly distorted the image of Lebanon.”

Instead of cleaning up the toxins, or holding accountable those who brought them to Lebanon, the Lebanese state conducted a campaign of persecution, intimidation and gaslighting against anyone who tried to document what the barrels contained. Security forces arrested and interrogated scientists and environmental activists who had publicly spoken or written about the barrels and their toxic contents. At one point, they even physically assaulted the scientists who were collecting samples from dumpsites.

“This is what someone who wants to hurt others would do,” said Wilson Rizk, one of the scientists who tried to track the barrels and their contents. “It’s direct harm. Some of the barrels’ contents were dumped in the environment, and we still don’t know the full extent of their dangers.”

The first half of our two-part investigation chronicles a story with eerie echoes of the port blast: of mafias and militias, of ghost ships bearing poison payloads and wealthy countries systematically dumping their contaminants on poorer ones. It traces how Lebanon, one of many destinations in this toxic trade, became entangled in a global web of front companies, organised crime syndicates, arms dealers and local criminals connected to a Lebanese militia.

The second half exhumes the long-buried scandal and follows it into the present day, exposing the lengths that Lebanon’s ruling class will go to in order to shield itself from any form of accountability.

The saga of the barrels is not Lebanon’s failure alone. It is one small episode in the ongoing crime that environmental scholars call “slow violence”: in this case, the long history of western countries using the Global South as a dumping ground for deadly substances.

The saga of the barrels is not Lebanon’s failure alone. It is one small episode in the ongoing crime that environmental scholars call “slow violence”: in this case, the long history of western countries using the Global South as a dumping ground for deadly substances.

By documenting the story of the toxic barrels, and revealing the government’s ongoing cover-up, we hope to provide a historic record and guide for those seeking justice for the blast. And we celebrate the persistence of all those who worked to uncover the truth – the scientists, activists, artists, lawyers, researchers and members of the public – who tried to hold the government accountable and made sure the scandal would not be quietly forgotten.

The poison ships

On 21 September 1987, during the twilight years of Lebanon’s 15-year civil war, the Czechoslovakian ship Radhost docked at the port of Beirut with the first of several shipments from Italy: 15,820 barrels of industrial toxic waste from Italian cleaning firm Ecolife, which had contracted the infamous Italian waste management company Jelly Wax to transport and dispose of the waste. According to a 1996 report by Greenpeace, the 2,400-tonne shipment contained a toxic cocktail of chemical compounds: flammable substances like methyl acrylate, ethyl acrylate, pesticides and heavy metal cyanides.

Lebanon’s military intelligence branch concluded that the Lebanese Forces (LF) militia, which controlled the port at the time, had allowed international chemical companies to use Lebanon as a toxic waste dump in exchange for “thousands of dollars.” Beirut Judge George Ghantous would later conclude that the payoff was $22 million.

By February 1988, the toxic deal was no longer a secret. Adonis Productions Engineering, the Lebanese company that had imported the toxic waste, issued clearance documents to Jelly Wax claiming that all 2,400 tonnes of hazardous waste unloaded in Lebanon had been incinerated or dumped in the sewage system. The documents were obvious fakes; aside from spelling errors, Adonis Productions forged the country’s official stamp using a pine tree instead of a cedar as the symbol of Lebanon.

The Lebanese Forces militia, which controlled the port, had allowed international chemical companies to use Lebanon as a toxic waste dump in exchange for $22 million.

When a lawyer from Ecolife asked the Lebanese consul in Milan to verify the documents, the consul informed the Foreign Ministry. The Lebanese media discovered the scandal, and the judiciary summoned six Lebanese Forces-affiliated suspects for interrogation: Antoine Kamid, Roger Haddad, Sami Nassar, Henri Abdallah, Antoine al-Amm and Dumit Kamid.

Adonis Productions Engineering, according to Greenpeace, was a shell company for Arman Nassar Shipping. Dumit Kamid was a customs agent. Roger Haddad was Arman Nassar’s cousin and head of maritime operations for Arman Nassar Shipping. The judiciary issued arrest warrants for all six, as well as a seventh: Arman Nassar himself, who was on the run.

Public prosecutor Munif Hamdan charged the six detained suspects with causing an “environmental disaster” and a “mass killing,” and called for them to be sentenced to death. But in July, Judge George Ghantous released all six suspects on bail. The judiciary concluded that four of the suspects – Antoine and Dumit Kamid, Henri Abdallah, and Sami Nassar – were not involved in importing the Italian toxic waste.

By September 1988, Beirut was split into two, with General Michel Aoun running a military government in its eastern district, and Prime Minister Salim Hoss running a second government in the west. In the chaos of the war’s end, the barrels were forgotten and the authorities quietly let the case drop.

The scientists

But not everyone forgot the barrels. Six months earlier, in March 1988, Prime Minister Salim Hoss had appointed three scientists – Pierre Malychef, Wilson Rizk and Milad Jarjou‘i – to track down the barrels and figure out what they contained.

The three scientists found out that militia members, waste importers and Adonis Productions Engineering had sold off much of the poison ships’ deadly cargo. Many of the barrels ended up scattered across Lebanon, either dumped as waste or repurposed for storage. Factories bought the toxic containers in order to use their contents as industrial raw material. Someone burned about 2,000 barrels in an open-air garbage dump in Bourj Hammoud near the Beirut Port. Someone else destroyed another 1,600 nearby in the semi-industrial Karantina neighbourhood. Hundreds of barrels ended up getting dumped in locations across the country, including rivers and streams, the Shnan‘ir quarry and valleys in the Keserwan region. In some cases, panicked residents even burned the poison containers.

Those who bought or sold the barrels left them dangerously close to people’s homes. They told those people that the barrels, and their toxic contents, were harmless – or even useful. People used the barrels to store food, drinking water and rainwater for farming. “Residents told us they were informed that some is shampoo,” said Dr. Ali Darwich of the Lebanese environmental activist group Green Line. Darwich conducted interviews with some of the people who lived next to the barrels. At least one of them, he said, died of cancer.

After months of public pressure, the Italian government agreed to retrieve the toxic waste and cover the costs for shipping it back. But the cleanup was a disaster of its own – one for which Lebanese taxpayers would ultimately foot the bill.

After months of public pressure, the Italian government agreed to retrieve the toxic waste and cover the costs for shipping it back – $10 million, according to then-Italian ambassador Carlo Calia. But the cleanup was a disaster of its own – one for which Lebanese taxpayers would ultimately foot the bill.

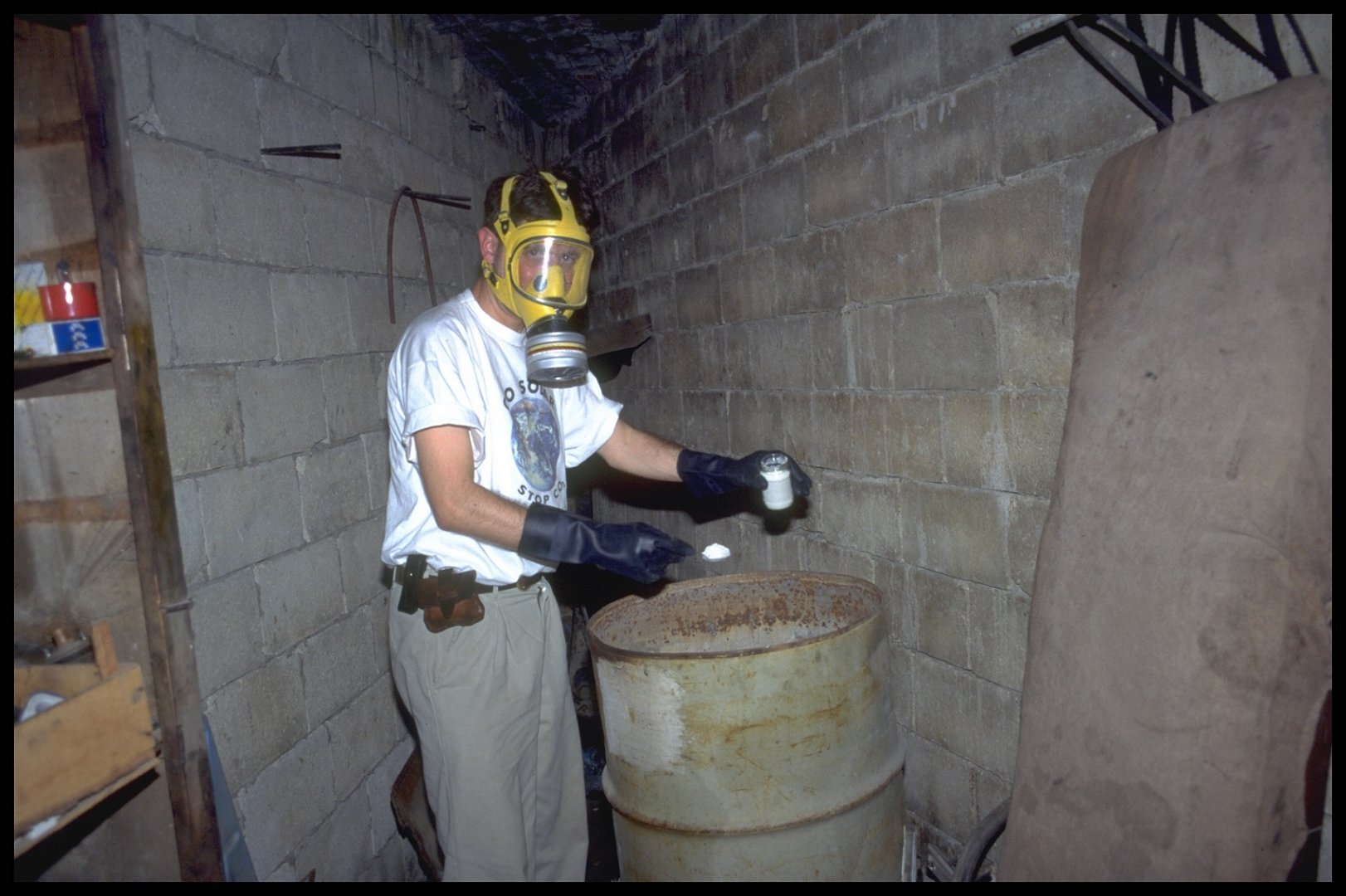

In August 1988, four Italian ships docked at the Beirut Port. Six Italian experts supervised as port workers struggled to transfer the toxic waste from 5,500 rusty barrels – about a third of the total – into new containers. Malychef and Jarjou‘i, two of the three government-commissioned scientists, took photographs as the corroded, leaky barrels broke open. Some of the workers even emptied the toxic waste directly into the sea.

The scientists tried to sneak on one of the ships, the Yvonne A, to take pictures on board. But the Lebanese Forces militia still controlled the port: militiamen caught the scientists, confiscated most of their film and kicked them out. “We were accused of being spies,” the scientists said in their report.

Luckily, they didn’t leave the dumpsite empty-handed: Malychef, thinking quickly, “hid some of the film he used in his socks,” Dr. Wilson Rizk told The Public Source.

The Italian ships left three months later, carrying less than a third of the toxic waste. Of those four ships, only one, the Jolly Rosso, ever made it back to Italy. What happened to the other three ships – the Cunski, the Voriais Sporadais and the Yvonne A – remains a mystery to this day.

In 1989, a Cypriot journalist informed Greenpeace about a radio conversation between two ship captains, of the Voriais Sporadais and an unknown ship, talking about where to dump waste. The trail grew cold until 2003, when Francesco Fonti, an informant from Italy’s notorious ‘Ndrangheta mafia, made explosive allegations that the Italian state paid the group to sink at least 30 ships carrying toxic waste.

According to Fonti’s testimony, the Cunski, the Voriais Sporadais and the Yvonne A docked in Cetraro, in southwestern Italy, after leaving Beirut. From Cetraro, the mafia took control of the vessels and sailed them into international waters to sink them using dynamite. Fonti claimed that he personally sunk all three ships.

In February 1992, under the newly passed amnesty law, the judiciary dropped all charges against the seven original suspects. For the next 35 years, the only people who would face serious questioning over the Italian barrels would be the scientists and environmental activists who tried to protect the public from toxicity.

Fonti’s cooperation with the Italian government in the mid-1990s led to high-profile arrests of the mafia’s drug traffickers. But it’s hard to tell if his testimony about the ships is reliable or not. Fonti alleged that a shipwreck 28 kilometres off Cetraro was the remains of the Cunski. The Italian government sent a ship to survey the wreck, only to conclude that it was a passenger steamship that a German submarine hit back in 1917. Italy immediately decided to call off searching the ship. In 2010, a Greenpeace report on the toxic waste trade questioned whether Fonti was really unreliable – or if the Italian authorities tried to cover up the search.

In 1990, the Lebanese civil war ended when its warlords agreed to share their spoils and modify the country’s sectarian power-sharing system. The Lebanese Forces and its allies militia-turned-political party became key officials in Lebanon’s Environment Ministry. They were in an almost perfect position to make sure what was left of the Radhost’s deadly content in Lebanon stayed hidden. Less than a year later, the authorities passed an amnesty law that pardoned most crimes that took place during the conflict.

In February 1992, under the newly passed amnesty law, the judiciary dropped all charges against the seven original suspects. For the next 35 years, the only people who would face criminal charges over the Italian barrels would be the scientists and environmental activists who tried to protect the public from their toxic contents.

Barrel paranoia

On 29 August 1994, a foul-smelling truck sped through the mountainous Keserwan district late at night. The truck carried Environment Ministry workers and 19 barrels of ethyl acrylate and methyl acrylate. The driver carried a gas mask.

Keserwan residents, horrified by the stench, notified each other of the suspicious vehicle. By the time the truck arrived at its destination – the Yahshoush stone quarry, near the Ibrahim River – a mob of angry residents had gathered. They stopped the workers from dumping the barrels and forced the police to reload them onto the truck.

Keserwan was not the only destination for the barrels. Throughout the 1990s, as Lebanon rebuilt after the war, the toxic barrels began to resurface across the country. As citizens, activists and scientists hunted for the deadly containers, the government did everything it could to stop them. The Environment Ministry, now strategically seeded with members and allies of the Lebanese Forces, would spend the rest of the decade trying to silence them. But a dogged band of scientists and angry citizens would refuse to stay quiet.

Keserwan residents, horrified by the stench, notified each other of the suspicious vehicle. By the time the truck arrived at its destination – the Yahshoush stone quarry, near the Ibrahim River – a mob of angry residents had gathered. They stopped the workers from dumping the barrels and forced the police to reload them onto the truck.

Then-Environment Minister Samir Moqbel, who later became Lebanon’s Defense Minister, described the reaction to the Keserwan discovery as “hysterical.” Moqbel and another advisor, Cesar Nasr, denied the barrels were from Italy. They also claimed that the waste was, as Nasr put it, “hazardous but not poisonous.”

Once again, the judiciary appointed the three scientists – Malychef, Jarjou‘i and Rizk – to test the waste inside the 19 barrels. They found toxic and carcinogenic substances and concluded that the quarry-bound barrels were likely leftovers from the Italian job.

The judiciary ordered the Environment Ministry to send the barrels to the Beirut Port and assigned the scientists to search for other toxic barrels from the poison ships. The ministry contracted British waste management firm Eurotech Environmental to transport the waste to the Beirut Port and ship it to the United Kingdom for incineration.

The British firm delivered the barrels to the port on 8 September 1994. Lebanon, a signatory of the Basel Convention at the time, would not ratify the international treaty that restricts the movement of hazardous waste until 21 December 1994. As a result, England could not legally take in waste from Lebanon to be incinerated.

On 15 November 1994, Greenpeace flagship the Rainbow Warrior docked in Beirut with scientists on board. Greenpeace and local environmental groups, including Green Line, demanded that the Lebanese government allow them to collect samples from the Yahshoush barrels and test them at the University of Exeter in England. Environment Minister Moqbel and Prime Minister Rafic Hariri met with the scientists on board the Rainbow Warrior two days later and finally gave them permission.

The Environment Ministry insisted it was handling the toxic barrels in an environmentally friendly way. Ministry consultant Nasr boasted in a press conference that the ministry had buried the barrels “scientifically,” by first “neutralising” the chemical compounds within them. “It couldn’t have any impact on the environment by doing this,” he said.

In January 1995, the Lebanese newspaper An-Nahar leaked a document revealing that Environment Ministry adviser Jamil Rima had secretly agreed with Keserwan official Raymond Hitti to dump the waste near the river. Outraged Keserwan MP Mansour al-Bon believed the barrels were from the Italian deal. He called for the case to be reopened.

That same month, Greenpeace announced that its tests revealed that the barrels contained flammable liquids methyl acrylate and ethyl acrylate, used to produce plastics, and toxic chlorinated paraffin. The environmental watchdog organisation added that the toxic material was similar to the barrels that came from Italy in 1987.

“The Lebanese Environmental Ministry made a mistake in the summer of 1994 when it tried to dump the acrylates in the Kisrwan Mountains,” Greenpeace stated in its scathing report. “Dumping is no solution for getting rid of toxic waste, and the mountains are an aquifer region. The acrylates are water soluble and could easily leak out and contaminate the groundwater supplies of an aquifer.”

In January 1995, the Lebanese newspaper An-Nahar leaked a document revealing that Environment Ministry adviser Jamil Rima had secretly agreed with Keserwan official Raymond Hitti to dump the waste near the river.

Then, as now, Italy was one of Lebanon’s top trading partners for imports, with close ties to the handful of political families that historically amassed vast fortunes through exclusive import deals. It was one of the countries pouring money into post-war Lebanon for its reconstruction.

Greenpeace called on the Italian government to take back approximately 10,000 barrels left in the country. Italian Ambassador Carlo Calia responded by claiming that Italy had taken back all the toxic waste back in 1988, and added that Greenpeace is “not very precise sometimes and not very good in judging.”

The day after Greenpeace released its findings, the Lebanese government reopened the investigation into the toxic deal, pledging to retrieve the remaining toxic barrels scattered across the country. The authorities appointed Judge Said Mirza to lead the probe.

On 7 February 1995, Malychef said on television that the toxic waste was still widespread across the country. The following day, Mirza issued an arrest warrant – for Malychef. The scientist was accused of “giving false testimony” on the toxic waste scandal on television. Malychef was arrested that same day. The next day, the judiciary transferred Malychef to a hospital, reportedly because of his heart condition. Lebanese authorities released Malychef from custody a month later, on 6 March.

Malychef continued to frustrate the authorities. One week after his release, he appeared on television again. But this time, he wasn’t alone: alongside him was Josée Maalouf, the widow of a port worker named Adib. She said he died because of medical complications he sustained after handling the toxic barrels at the Beirut Port. Judge Mirza, once again, issued an arrest warrant for Malychef. This time, he claimed Malychef “incited” Maalouf to give false testimony about her husband’s death.

Greenpeace continued to investigate the scattered toxic barrels in Lebanon alongside the three scientists and activist groups. In May, spokesperson Fouad Hamdan visited Lebanon from Germany for 10 days to collect and test samples of contaminated soil, ashes from burnt toxic waste containers and paint from homes and factories. “I saw nearly some 100 barrels of different sizes burned and leaking as well as burned ashes,” Hamdan told United Press International after visiting towns in northern Lebanon. Residents told him they saw toxic barrels brought in to be dumped, burned or left out in the open.

Hamdan moved to Lebanon in September 1995 to establish the country’s first Greenpeace office and focus solely on the case of the toxic barrels. “How often was I called during that time?” Hamdan said, in a 2015 interview with The Daily Star. “Barrels in that valley, barrels here, barrels there … there was barrel paranoia in the country.”

On 12 September 1995, Environment Minister Pierre Pharaon announced that the ministry had commissioned a French company to research and test hazardous waste in Lebanon. Pharaon claimed that the French company’s report revealed that “there is no toxic waste and no pollution in Lebanon.” The report was never made public; the toxic barrels case was closed.

But Hamdan obtained a copy of the report through a leaker. According to him, the French experts had in fact found traces of toxic waste after conducting tests in the Shnan‘ir quarry, near the port city of Jounieh, and Zouk Mosbeh, north of Beirut.

With the leaked French report in hand, Hamdan accused Pharaon of lying and deliberately misinterpreting the findings of the report. Justice Minister Bahij Tabbara issued an arrest warrant – for Hamdan, on charges of “damaging Lebanon’s image abroad and the country’s tourism industry.” Judge Mirza summoned him for a three-hour interrogation the next day.

Hamdan probably had the goods, because several days later, Greenpeace struck a deal with the Environment Ministry. Greenpeace would collaborate on the government’s investigation. In return, Pharaon allegedly promised to publicly reveal all of the details surrounding the 1987 toxic deal, keep the public informed of all the investigation’s developments, and decontaminate the Shnan‘ir quarry.

The blue barrels

As a child, Jessika Khazrik grew up hearing rumours about the haunted quarry. “You would hear stories about how hyenas would gather at night in the quarry,” she said.

But it wasn’t until much later, when her aunt passed away from a rare cancer, that she first learned about the barrels. “While we were welcoming people to express their condolences, someone said, ‘it was from the blue barrels,’” Khazrik recalled.

“Suddenly people started frantically talking about them.”

“What are the blue barrels?” she remembers asking the person seated next to her. But they wouldn’t answer her question. Later that day, Khazrik’s mother told her the barrels were the same ones she had passed every day on her way to school as a child. But in those days, nobody knew they were toxic. “People initially thought they just contained agricultural chemicals,” she said.

The Shnan‘ir quarry had been a key dumping site for the Italian barrels and other hazardous waste from the beginning. In 1987, a young man whom the Lebanese Forces had hired to guard the site died of cancer after using some of the barrels’ contents as insecticide and soap.

A Franciscan nun who ran a school near the quarry said she tried to warn him. “We said, ‘You have to be careful. These chemicals may be very toxic,’” she told Public Radio Exchange. “But he kept insisting, ‘It’s only paint. It’s not dangerous.’” He died 10 months later.

Shnan‘ir was not the only place to be poisoned by the barrels. Greenpeace, along with the three scientists and activist groups, also found toxic barrels in Oyoun el-Siman, in the mountains north of Beirut, above an aquifer that fed the capital’s drinking water. Residents and shepherds said they were getting sick from eating dairy products from animals grazing in the area, and that their livestock died after drinking contaminated water. Malychef said hundreds of sheep died.

Meanwhile, scientists suspected that some of the barrels had found their way to the Bourj Hammoud dump. Dubbed the “garbage mountain,” it towered at over 30 metres above sea level, which the scientists said made retrieving the toxic barrels virtually impossible. “I thought it must have been like Chernobyl or something,” said Dr. Ali Darwich, of Lebanese environmental activist group Green Line. “Nobody knew what was in there, but you would just see fires.”

Darwich and others requested permission to enter the Bourj Hammoud dumpsite and collect soil samples. The government denied it. Darwich said the government did everything it could to silence activists and scientists at the time – especially Rafic Hariri, Lebanon’s billionaire prime minister, who was leading the country’s post-war reconstruction. “Rafic Hariri was carrying his eraser to erase everything,” Darwich told The Public Source. “We tried to get a permit through the prime minister’s office, but Hariri didn’t want to let anyone in.”

Darwich and two others sneaked into the dumpsite to take pictures and collect samples. But the scavengers at the site who collected recyclable waste attacked them with sticks and metal rods. “We ran away and got to the Dawra fishing port and tried to escape in the car,” Darwich recalled. “But the guys got to us, carrying sticks and other things.”

Darwich believes the government allowed the scavengers to use the site in exchange for keeping activists and scientists out. In the end, the army and intelligence in the area hauled Darwich and his two companions to the Bourj Hammoud police station. Police held them for several hours before releasing them.

“Rafic Hariri was carrying his eraser to erase everything. We tried to get a permit [to enter the Bourj Hammoud dumpsite and collect soil sample] through the prime minister’s office, but Hariri didn’t want to let anyone in.” —Ali Darwich, Green Line

On 4 April 1996, Greenpeace discovered that the Lebanese government had secretly sent 77 tonnes of toxic waste and “contaminated land” to France to be incinerated at Lebanese taxpayers’ expense. The organisation said the shipment contained toxic waste that the authorities collected as far north as Tripoli. According to Greenpeace, the government “reluctantly” confirmed the news to them, admitting that most of the waste was from the 1987 Radhost shipment.

A month later, Greenpeace ended its alliance with Pharaon and the Environment Ministry for failing to fulfill its various promises: to publicly reveal all the details of the 1987 Italian deal, to track down the remaining toxic waste across the country, and to clean up the Shnan‘ir quarry.

When Hamdan asked Pharaon, then the environment minister, why he wouldn’t call out the Italian government for not returning the rest of the barrels, Pharaon’s response was the last straw. “He answered that the European Union, including Italy, is giving Lebanon millions in grants and aid,” Hamdan wrote in his 1996 report, “and therefore it would be inappropriate to embarrass Italy with the toxic waste.”

The most beautiful fight

The Lebanese government closed off the Bourj Hammoud dump in July 1997. But activists and residents were still finding barrels and hazardous waste all over the country: in the Metn mountain town of Monteverde, Greenpeace discovered 120,000 tonnes of waste and contaminated soil that the government had clandestinely transferred the waste to Monteverde from an open-air dump in Karantina, eight kilometres away. They suspected it was from the Italian job. Following public outcry, the authorities removed the waste – back to the Karantina dump.

In January 1998, workers in the contaminated Shnan‘ir quarry were extracting rocks for the construction of a coastal highway when Lebanon’s cabinet issued a decree to shut down the quarry. But the Mount Lebanon governor, who had issued the quarrying licence to the owners of Shnan‘ir, ignored the government’s order to close down the contaminated site.

That summer, factory owners bought the empty toxic barrels and used them to store oil and asphalt for construction. Instead of confiscating the barrels, the Environment Ministry asked the factory owners to clean the barrels and remove warning stickers and labels, so as not to alarm businesses and residents. “[P]eople see the barrels in their villages that still have a sticker with a skull and crossbones on it and they think it contains toxic material,” a ministry spokesperson told the Daily Star. But if the barrels were properly cleaned, said the Ministry, “then they can be used for anything.”

Fouad Hamdan, the relentless Greenpeace campaigner, pointed out that the emptied toxic barrels should have been sent to a steel recycling plant and kept away from the public. “It is unbelievable and irresponsible that the ministry is promoting in an indirect way a polluting and dangerous method of toxic waste disposal,” he said.

Six months later, in early February 1999, Hamdan left Beirut and returned to Germany. “The past four years aged me 40 years,” he said, describing his exasperating period in Lebanon as “the most beautiful fight of my life.”

A few weeks later, Lebanese State Prosecutor Adnan Addoum officially closed the toxic barrels case, claiming the waste “did not prove harmful to human health, to the environment or to animals.” Hamdan’s successor, Ghassan Geara, held a press conference with Malychef, Jarjou‘i and Rizk. They disputed Addoum’s decision and insisted that the waste was indeed toxic. The following day, Addoum summoned them for interrogation, accusing them of giving false testimonies.

The next month, the Lebanese government began unloading garbage into the sea in order to expand the Beirut Port’s capacity with artificially reclaimed land. The garbage came from an open-air dump in Karantina – the same one that, according to Greenpeace, contained waste from hundreds of the Italian barrels. Greenpeace and environmentalist groups protested at the port. Geara called the dump a “toxic concoction” that contained medical and industrial waste.

The Beirut Port Authority responded that it was using “cleaner material” as a barrier between the Mediterranean Sea and the contaminated garbage. However, Geara told The Daily Star he believed the supposedly “cleaner” material was actually just the contaminated soil from the port that had been secretly dumped in Monteverde, and then brought back to the port. In the end, despite protest from Greenpeace and other groups, the government-contracted companies continued dumping the contaminated waste into the sea.

Coda

Italy’s poison ships docked in many other countries. But one incident became a defining moment in the short but violent history of Italy’s toxic dumping trade. In 1988, Jelly Wax and another Italian company called Ecomar transported over 2,000 toxic waste barrels to Koko, a Nigerian fishing town. Villagers fell ill after the toxic waste seeped into the soil and groundwater.

The Koko incident caused massive outcry, both in Italy and worldwide. In March 1989, the international community adopted the Basel Convention restricting the international movement of toxic waste. Italy and Lebanon both ratified the convention in 1994. The convention later included a 1995 Ban Amendment that banned most European countries from exporting waste entirely; Italy and Lebanon both ratified it, in 2009 and 2017 respectively. (The amendment only went into force in 2019.)

The Koko scandal sparked grassroots mobilisations in Italy. After years of pressure, the Italian authorities finally passed comprehensive waste management legislation in 1997. But Italy wouldn’t make environmental crimes a felony until 2015.

Lebanon passed a law that criminalised importing hazardous waste in August 1988, months after the toxic deal was public, around the time the four Italian ships docked at the port to retrieve a small fraction of the toxic containers.

Following years of threats, attacks and no progress, the three scientists finally gave up. Pierre Malychef had paid a high price for his dedication to uncovering the truth. He was physically attacked several times. His pharmacy was blown up twice. He was diagnosed with skin cancer in 1988, after a drop of toxic waste landed on his neck; fortunately, he recovered. Malychef passed away in June 2014. Today, Rizk is the sole survivor of the three scientists.

But their work lives on to this day. Three months after Malychef passed away, Jessika Khazrik approached his family. “His family welcomed me after I told them my story,” she said. “Malychef always dreamt and knew that someone else would reinvestigate.” For the next eight years, she combed through Malychef’s photos, documents, reports and anything else he had collected while investigating the toxic barrels. Khazrik continues to share the story of the toxic barrels on panels and at conferences, and she has displayed archived photos and artworks based on the story in museums around the world.

The Italian job wasn’t done with Lebanon either. Its remnants would re-emerge years later when the Lebanese government decided to take down the towering Bourj Hammoud dump and landfill it in the Mediterranean Sea. The second part of our investigation looks into how the cover-up of the 1987 toxic deal continues to this day.

Reporting by Christina Cavalcanti and The Public Source contributors.

Additional research by Ranine Awwad.

With editorial support from Sintia Issa and Simon Assaf.

IMS’ reader on environment in the MENA region

The pieces published here tell the story of the way the environment has been understood and questioned by our partners in the MENA region.