TuNur: what lurks in the shadow of the Tunisian sun export to Europe?

Exporting the Tunisian sun to Europe has been the ambitious vision of the Tunisian-British company TuNur for the past ten years, as it plans to develop a mega solar power plant in southern Tunisia. This project will, however, inevitably have an impact on local communities and resources. Mounting demands for a just transition model are being voiced in this piece by Inkyfada.

By Aida Delpuech and Arianna Poletti

Importing the Saharan sun to secure a clean, low-cost energy supply has been the dream of European countries and certain stakeholders in the private energy sector for decades. Projects involving the export of solar energy from North African deserts to European shores have come to light once again today, after having been placed on the back burner for some time.

In Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria and Egypt, companies have set up in the desert where they plan to build mega solar power plants in order to export this energy to Europe. But are there really no consequences for the populations and resources as these companies claim?

North Africa: Europe’s new energy field

This article was originally published 11 November 2022 by inkyfada. Through combining explanatory and contextualising articles with data journalism, portraits and investigative and in-depth reporting, inkyfada aims to provide accessibility to parts of society that too often remain hidden from the general public, contributing to a better understanding of the world around us.

Amid an energy crisis triggered by the war in Ukraine and a cold, dark winter on the horizon, Europe is desperately seeking to free itself from Russian gas by diversifying its sources of supply. Over the past few months, European States have been keeping a close eye on their southern Mediterranean neighbours’ resources. As the leading African exporter of natural gas, Algeria has now become Italy’s largest supplier, followed by Russia. Since the early 2022, nearly 20 billion cubic metres of gas have been transported via the Transmed pipeline.

While oil prices have been soaring, European countries have also been pragmatically working to fast-track their shift to increasingly cheaper renewable energy. In September 2022, the EU announced its RepowerEU plan aimed at increasing its renewable energy target to 45 percent by 2030.

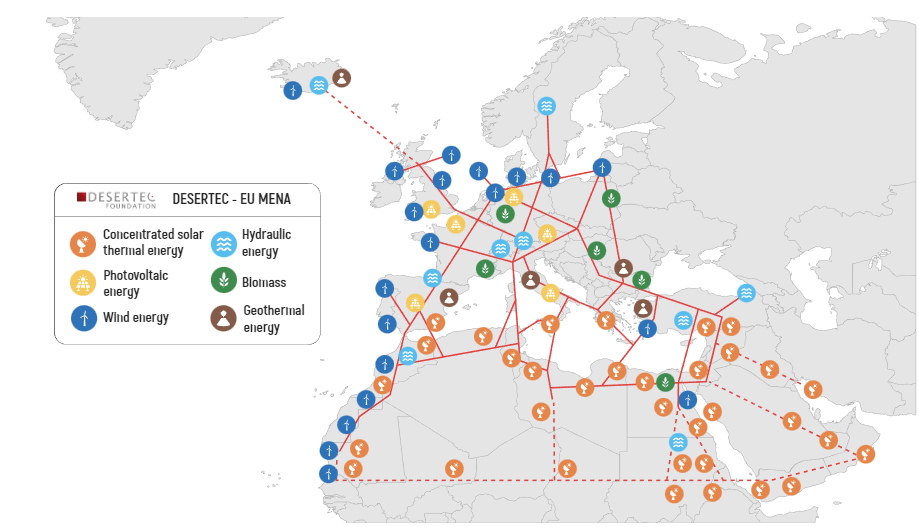

However, the Old Continent does not intend to produce all of its green energy needs on its own territory and is keenly focused on the solar potential of its North African neighbours, a region with one of the highest solar capacities in the world. So far, several mega solar power plant projects are underway, with a view to exporting electricity to Europe via submarine cable systems.

In southern Tunisia, on the Algerian border, a gigantic solar power plant developed by the Tunisian-British company TuNur may spring up in the upcoming years. The latter aims at “providing low-cost electricity to 2 million European homes,” through a transmission line linking Tunisia to Europe via Italy, and thus reducing CO2 emissions by five million tonnes per year, according to an announcement made by the company.

While these words might sound responsible and reassuring, these mega-projects will almost certainly have an impact on the local population and resources. While only 3 percent of Tunisia’s electricity is generated from renewable energy, and the country is struggling to meet its climate objectives because of the prevailing financial crisis, many foreign private investors are actively targeting Tunisian solar resources for export.

“I have my doubts about the contribution of these projects at the local level,” says Benjamin Schütze, an international relations researcher at the University of Freiburg (Germany) and author of a report on the socio-economic impacts of solar energy in the Middle East and North Africa.

The entirety of the green electricity production would be directly transmitted to the northern shore of the Mediterranean, with absolutely no benefit to the local populations. While the COP27 climate negotiations in Egypt are underway, demands are growing for a just and sustainable transition. Will Europe achieve its energy shift in part at the expense of North Africa? inkyfada investigates.

TuNur, the ultimate export fantasy

On the road leading to Rjim Maatoug bordering Algeria, 120 kilometres from Kebili in southern Tunisia, oil tank trucks are the only vehicles passing each other in a never-ending back and forth cycle between the various deposits in the south. This desert area, which was once home to nomadic communities, has become inaccessible unless otherwise authorized by the Ministry of Defense.

These formerly collective lands were divided among the country’s large southern tribes whose main source of livelihood was pastoralism. Occupied during the French colonisation, these lands were then reclaimed by the Tunisian state after gaining its independence, which then progressively ceded them to private companies, notably oil multinationals, wishing to invest in the country.

In the military-controlled area of Rjim Maatoug, there is a series of identical villages bordered by a new palm grove stretching over 25 kilometres. “Prior to this, there was nothing but desert. We have created this new oasis in order to prevent the desert from advancing and to allow the nomadic communities to settle down,” explained a military officer present at the scene.

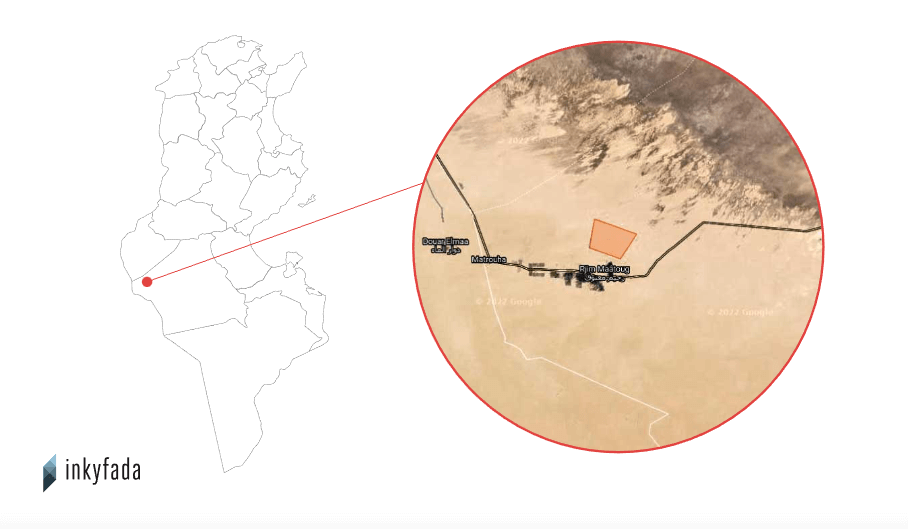

According to planning documents examined by inkyfada, a giant solar power plant developed by the Tunisian-British company TuNur might be established right opposite these palm groves, which were introduced in the late 1980s thanks to European funds, namely those granted by the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation (AICS).

“Solar and wind energy are inexhaustible, and Tunisia has an abundance of both,” stated the company on its brand new site. TuNur is planning to produce 4.5 GWh of electricity destined for export to Italy, France and Malta.

Operating in Tunisia since late 2011, the company has announced the impending development of what could be the world’s largest Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) plant on multiple occasions, but so far the project has remained dormant. Many industry professionals have deemed the idea “unrealistic” due to its extremely high cost. Despite this, in August 2022, the CEO of TuNur announced that an initial investment of 1.5 billion euros was being considered for the project’s implementation.

In an interview with inkyfada, Ali Kanzari, TuNur’s Senior Advisor in Tunisia and President of the Tunisian Photovoltaic Trade Union Chamber (CSPT), stated that “trade with Europe is strategic, and should not be limited to dates and olive oil.” According to him, it is mainly “the political will” that is lacking: “Tunisia is at the heart of the Mediterranean. We are perfectly capable of meeting Europe’s ever-growing green energy needs, but we still fail to exploit our own desert.”

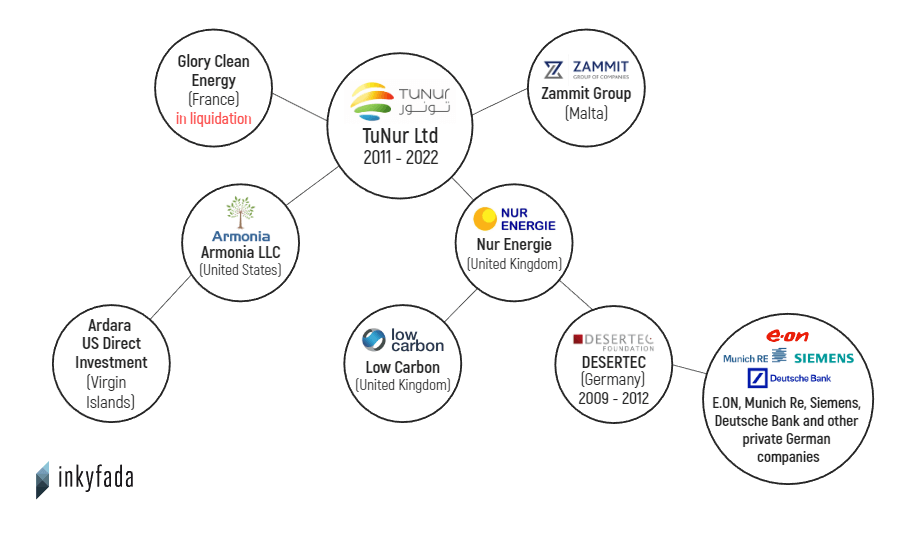

Although no solar panels have been installed so far, this is hardly the solar export moguls’ first attempt. TuNur is part of the Desertec Industrial Initiative (Dii), involving partners such as Nur Energie. This monumental project was initiated in 2009 by an international consortium of mostly German companies. Major players such as E.ON, Munich Re, Siemens and Deutsche Bank have become shareholders.

Heavily criticised for its extractive designs, the project was intended to “revolutionise the energy industry with the greatest idea of the 21st century”: harnessing solar energy from the world’s largest desert, the Sahara. Industrialists were hoping to develop a network of concentrated solar thermal power plants in North Africa and the Middle East. This would cover more than 15 percent of Europe’s electricity needs by 2050, paving the way for European economies to grow “in balance with the environment”.

Due to internal discord and a lack of funding, the entire project fell through and was dropped in 2012. However, the willingness to support Europe’s energy transition through North African solar power persisted and is now being revitalised in light of the current global energy crisis. TuNur, a project based in Tunisia and a localised version of Desertec, is backed by a handful of investors and four employees, including its director, English businessman Kevin Sara, as per the 2022 annual report consulted by inkyfada.

As the founder of Hazel Capital, a UK-based venture capital trust, the head of the Chinese investment group Astel Capital and former member of the Japanese financial giant Numura Holdings, Sara is one of London’s leading names in the high finance industry. He is now investing in the thriving renewable energy market. Assisted by his Tunisia-based executive director, Daniel Rich, Sara is also the CEO of Nur Energie, a British solar power plant developer that he started in 2008. It is active in Italy, Greece and Morocco, and managed by a British Virgin Islands-based investment fund.

Joseph Zammit, a member of the powerful Maltese Zammit family, is believed to be behind “the diversification of the group’s interests in renewable energy initiatives” as stated on the company’s website. For his part, Cherif Ben Khelifa, a petroleum engineer by training, has worked with companies such as Total, Shell, Noble Energy and Lundin. TuNur has repeatedly declined to be interviewed by inkyfada.

Sacrificing natural resources for solar energy: the case of Ouarzazate, Morocco

Tunisia is not the first North African country where private companies are bidding to exploit the desert’s “solar potential”. TuNur is inspired by a mega Moroccan solar power plant developed under the heavy influence of the Sharifian monarchy, where the Desertec Industrial Initiative was planning to launch its first export project.

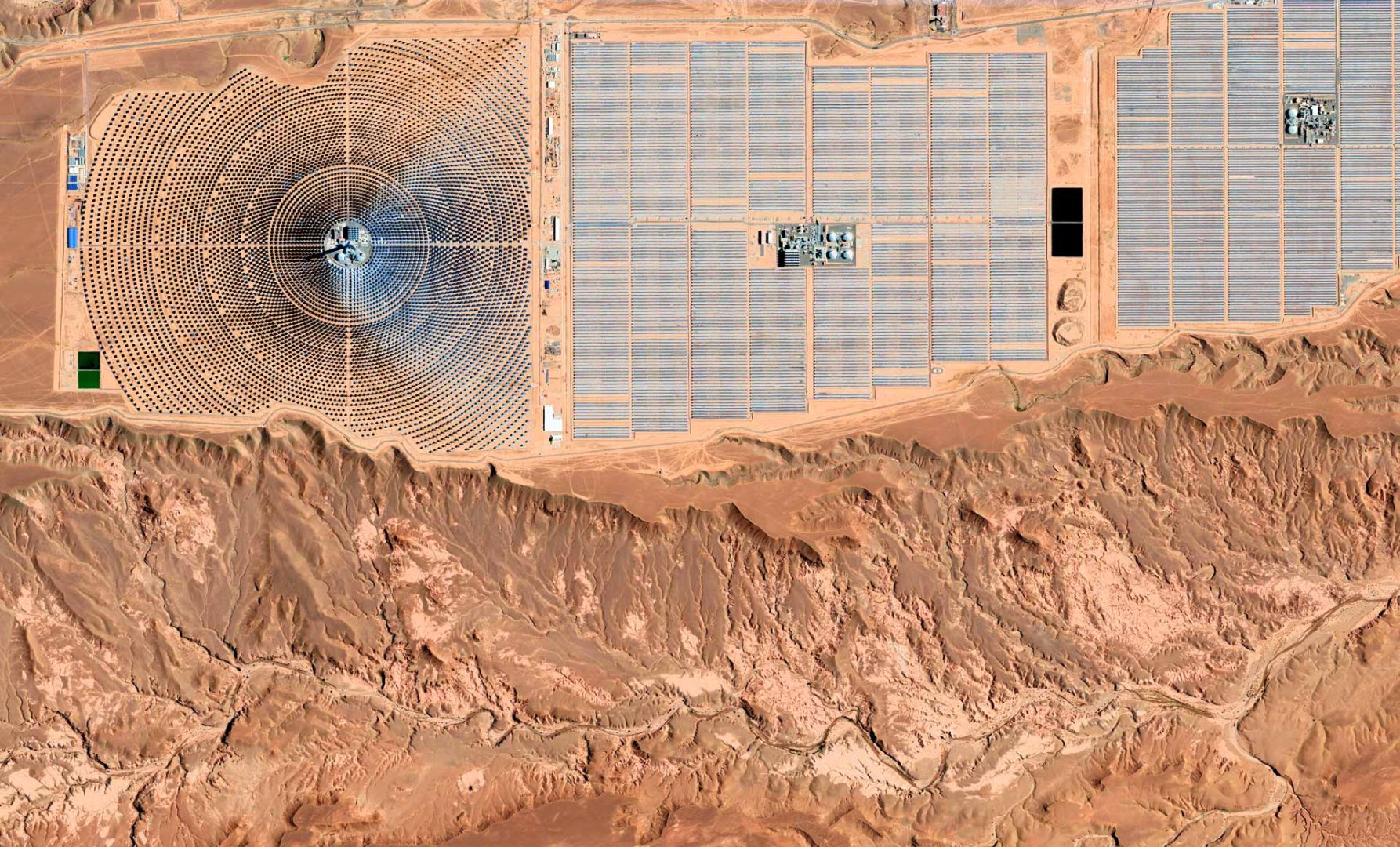

Officially inaugurated in February 2016 in Ouarzazate, the world’s largest thermodynamic power plant – Noor – has become the hallmark of a national policy geared toward the expansion of renewable energy. With 37.6 percent of its energy mix (energy mix is the breakdown of the different energy sources) comprised of renewables, Morocco is striving to become the Mediterranean hub for renewable energy and has designed its solar plan not only as an economic development initiative, but also as a potentially export-oriented policy.

The gigantic Ouarzazate project, celebrated by the media, is conceptually very similar to TuNur, although its production is not export-oriented, unlike the Tunisian project, and has since become the symbol of the country’s transition. With an installed capacity of 580 MWh, the site is now managed by the Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy (Masen) and the Saudi group ACWA Power.

In the uneven rocky terrain of southeastern Morocco, shrouded in brownish dust, hundreds of light strips have popped up and imposed their strict geometric order across an area of 3,000 hectares. Semi-parabolic mirrors that rotate automatically throughout the day to reflect the sun’s rays onto a thin tube placed in the center of the machine. There, a liquid gets heated and collected at the heart of the complex, where it powers a turbine used to generate electricity.

Such is the technology of concentrated solar thermal power (CSP) – quite different from photovoltaics – which is used not only in the Moroccan plant, but also in the Tunisian TuNur project, as well as in other large-scale projects intended for export. “Using CSP allows us to store energy for an average of five hours, which is significantly more profitable than using batteries,” said Ali Kanzari.

The construction of the Moroccan Noor complex was carried out by several major German groups. For instance, the electronics giant Siemens, a member of Desertec, had manufactured the turbines, which are exclusively dedicated to CSP technology. Sources in the independent Moroccan media Telquel reported that the project funders – the World Bank and the Kfw [German development bank] – have called for the adoption of this technology, defending the German equipment manufacturers’ interests. However, many aspects of this technology, notably its intensive use of water, should have prompted them to exercise greater caution.

Today, CSP is posing a serious threat to the region’s resources. One of the biggest concerns is the technology’s substantial water requirements for washing the solar reflectors in a desert environment, and during the wet cooling phase. The environmental impact study that was conducted prior to the construction of the project predicted an annual water consumption of 6 million cubic metres to be taken from El Mansour Eddahbi dam’s surface water, located a few kilometres east of Ouarzazate, and currently operating at 12 percent of its total capacity.

“It’s impossible, however, to get official statistics on the actual consumption,” pointed out researcher Karen Rignall, an anthropologist at the University of Kentucky and a specialist in rural energy transition who has been working on the Noor solar plant for a long time.

“An official at the Office for Agricultural Development in Ouarzazate, which is in charge of this dam, has anonymously admitted to us that the Noor complex has failed to communicate its water withdrawals to them. The real consumption seems to be considerably higher,” she added.

In a country experiencing “structural water stress”, as described by the World Bank, Ouarzazate is one of the most barren regions in Morocco. In the Dades Valley, a river flowing into the dam, Youssef, a farmer, depicted an alarming situation:

“Our valley is about to collapse, all of our water is being redirected to the dam to meet the needs of the solar power plant. This project is a disaster and is far from being an alternative,” he exclaimed, while walking through the dry palm trees of an ancient oasis.

Each village in the Dades Valley, famous for its rose cultivation, bears the name of the river running through it. Today, bridges overhang dry wadis full of nothing but pebbles. A few kilometers away, in the equally dried-out Draa Valley, “thirst protests” have been ongoing since 2017. The locals have been criticising the state’s appropriation of water resources for major agricultural, mining and energy projects.

“All of these cases involve extractivism. These are projects that have been imposed on us from above and that rob us of our most expensive resource: water,” condemned Jamal Saddoq of the Attac Maroc association in Ouarzazate, one of the few bodies to challenge extractivist policies and authoritarianism in the country.

“It really is ironic how a project that is meant to mitigate climate change is actually aggravating its impact on one of the poorest and most water-stressed regions in Morocco,” observes Karen Rignall.

In southern Tunisia, TuNur is seeking to develop a similar project that is nine times as large. Just like in Morocco, the oasis system is equally damaged by droughts and poor water resource management. According to the Nakhla association, which works with farmers in Douz (Kebili), the region is already using 209 percent of its current water resources.

Water pumping installation in El Faouar.

Capitalising on the desert by any means necessary

TuNur did not wait for a tender by the Ministry of Energy for a concession for export, which is a must for any renewable energy project in Tunisia. Before any impact study was conducted on water resources, the company had already “signed a pre-lease agreement for a 45,000-hectare plot of land located between the towns of Rjim Maatoug and El Faouar with the El Ghrib Collective Land Management Council, which owns the site,” said Ali Kanzari, Senior Adviser for the project.

The solar power plant would cover 25,000 hectares, almost three times the size of Manhattan, an unprecedented undertaking. Yet, despite TuNur’s investment announcements, the project seems to be on hold until the Ministry of Industry, Mines and Energy grants its approval for an impact assessment.

Site pre-leased by Tunur in Rjim Maatoug.

“We have an unexploited desert,” lamented Kanzari. Like many private and public stakeholders in the renewable energy sector, he regards the desert as nothing more than a vast wasteland with greatly untapped potential.

“This ‘useless desert land’ narrative is directly rooted in the French colonial era, when the colonial power sought to counter the opposing southern tribes by taking away their land,” said Aymen Amayed, a researcher in agricultural policies.

After independence, Habib Bourguiba adopted the same approach, claiming that the desert lands were useless since they were not nearly profitable enough. “In reality, however, they were extremely lucrative for the local population, whose primary activity was grazing,” added the researcher. A vast campaign of land dispossession followed, which is still happening to this day. “By expanding its land reserves, the state has created abandoned areas, set aside for future economically more profitable and highly capitalised ventures, such as today’s renewable energy projects”.

These same lands, whose “uselessness” was consciously constructed by successive land policies, are now being pursued by the world of green finance, with the promise of stimulating “marginalised” regions in the name of sustainable development. TuNur promised to create more than 20,000 direct and indirect jobs in a region where the number of people seeking to leave for Europe is on the rise.

But with these mega projects, “most of these jobs are not sustainable, most of them are only needed for the construction and start-up phases of the projects,” as a recent report by the Tunisian Observatory of the Economy pointed out.

Semi-desert area south of the Chott-el Jerid.

A mounting number of researchers and observers believe that the present framework for these projects only leads to “the appropriation of land in underdeveloped areas for the purpose of exploiting renewable resources, without proper compensation for local communities, thereby fostering an internal colonial dynamic,” stated Karen Rignall.

These mega-projects typically entail the need to raise substantial capital from the get-go. However, “most public players in the southern Mediterranean are in debt and have no such capital at their disposal. This is where private stakeholders take over, allowing the benefits to go to the private sector and the costs to the public sector,” explained researcher Benjamin Schütze.

The Noor solar power plant in Ouarzazate, the project that inspired TuNur, is a case in point: since its construction, the Moroccan plant has not been economically viable, and the state has been running a deficit of 800 million dirhams per year (about 75 million euros). This was because Masen, the Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy, had guaranteed the private Saudi company managing the plant an extremely high energy sale price compared to the average energy production cost in the country. It was also partly due to the choice of the outdated CSP technology, which was far too expensive, as pointed out by the Economic, Social and Environmental Council (CESE), an independent Moroccan consultative institution.

“Besides, this deterministic depiction of the desert is also a way of outsourcing the European energy transition and our responsibilities towards the climate crisis. It is an easy solution. Since Europe has no intention of changing its consumption pattern, it aims to build mega power plants in order to provide green electricity. This is very problematic,” denounced Benjamin Schütze.

The scholar believes that these mega-projects, which require centralised production, are also easier to implement in authoritarian contexts. In Tunisia, if access to land once represented a major roadblock to the deployment of solar and wind projects, the tide has recently turned. On 19 October 2022, the decree-law no. 2022-65 was issued with little to no media attention. This recent legislation provides for the possibility, for any public entity, to get its hands on any kind of land, and thereby expropriate its owner, for the implementation of a “public utility” project.

On the same day, another decree was issued (No. 2022-68), enabling renewable energy production projects to be carried out on public agricultural and non-agricultural plots or on those owned by local authorities under lease agreements. “The door is now open to foreign investors, who work hand in hand with the State,” said Aymen Amayed.

Two-sided lobbying

Even though TuNur’s solar power plant has so far only existed on paper, the company, which has been established in Tunisia since 2012, has stepped up its activities since 2017. While waiting for the Ministry of Energy to issue a tender for export, the company has placed itself on the local market with the construction of one of the first solar power plants in Tunisia (10MW) in 2019, in Gabes, in southeast Tunisia. “The company has been in Tunisia for 10 years now, it’s about time it started making money,” explained Ali Kanzari.

07/06/2022 : TuNur Team site visit to Gabès to meet with representatives of the local authoritieshttps://t.co/AZ4SomPN3l

— TuNur Ltd. (@TuNurSolar) June 8, 2022

07/06/2022 : Visite sur site de l'équipe de TuNur à Gabès pour rencontrer des représentants des autorités locales https://t.co/jidyBSW74upic.twitter.com/xzAD5cCcN8

If TuNur has made any progress in recent years, it was mainly in the lobbying business, both in Tunis and in Brussels. Since 2020, the company has been listed in the EU Transparency Register, a database of organisations seeking to influence the legislative process and the implementation of European institutions’ policies. TuNur’s focus lies more on influencing legislation on energy and neighbourhood policies in the Mediterranean.

The company seems to show particular interest in the European Green Deal and the European Network of Transmission System Operators, an association representing some 40 electricity transmission operators. “We need the Tunisian state to work with us in order to develop a roadmap with European countries, to ensure that Tunisian clean energy can compete on the market,” explained the consultant Ali Kanzari, who confirmed that TuNur has already contacted electricity distribution companies in both Italy and France. TuNur is one of the projects that have been shortlisted in the joint European Ten-Year Network Development Plan (TYNDP) for 2022, a necessary step to join the ranks of the EU’s Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) in the interconnection of European energy networks. Once selected, projects may benefit from simplified regulation and qualify for EU financial support.

The influence of private groups operating in the country, and specifically TuNur, is also widely observed in Tunisia. “This project organised a powerful lobby that sought to obtain the inclusion of provisions relating to exports in the renewable energy legislation,” as confirmed in the latest energy report of the Tunisian Observatory of Economy (OTE), which analysed the cases of Desertec and TuNur.

Law No. 2015-12 on renewable energy, which was approved in 2015, has effectively paved the way for green energy export projects. This was done by allowing the liberalisation of the electricity market in Tunisia, which had until then been monopolised by the state-owned Tunisian Company of Electricity and Gas (STEG), an institution heavily burdened with debt. The law also encouraged the use of public-private partnerships (PPPs).

“Some recommendations made by the German Agency for International Cooperation Development (GIZ) and Desertec Industrial Initiative (Dii) appear to have anticipated some of the measures included in the 2015 law,” noted yet another report by OTE. Amended in 2019, this law has been widely challenged by a group of STEG unionists, members of the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT), who called for electricity prices to continue being regulated by the state, since it is still subsidized in the country.

Two years after having fought against the sector’s privatisation in 2018, the public company’s unionists ultimately blocked the grid connection of the first private power plant built in the country, located in Tataouine. This 10 MW photovoltaic power plant, co-financed by the French Development Agency (AFD), is owned by the company SEREE, a joint venture between the Italian oil company ENI and the Tunisian Company for Petroleum Activities ETAP.

“We are urging the state to revisit this law that was ratified under pressure from multinationals. We’re not against renewable energies, we’re simply demanding that they be made available to Tunisians, electricity must remain a public property,” explained an anonymous unionist who took part in the grid blocking operation.

Three years following the completion of the construction work and a lengthy standoff with the unions, the plant was eventually connected to the STEG grid in early November 2022.

“Solving the grid connection problem of renewable energy plants” was one of the first recommendations made by the World Bank in a report addressed to the Tunisian Ministry of Economy in late 2021. Meanwhile, the IMF has been promoting investment in renewable energy through its new economic reform program that is currently being negotiated with the Tunisian government. “Pressure has been particularly mounting since the Russian gas crisis hit Europe,” concluded the unionist.

Today, even with legislation favourable to private projects, construction work on most of the renewable energy projects already approved in Tunisia, all of which have been won by foreign companies, has so far been halted. The reason: “The slowness of administrative procedures in Tunisia. In the meantime, the cost of raw materials for the construction of our projects has substantially gone up on the international market,” commented Omar Bey, Head of Institutional Relations at the French company Qair Energy.

Big companies seem to be the only ones able to afford the gap between the initial budget and the current construction prices. Gathered under the Solar Power Europe banner, a Brussels-based organisation involving over 250 companies such as TotalEnergies, Engie and EDF, the Italians ENI, PlEnitude and Enel, but also Amazon, Google, Huawei and several international consulting firms, these entities participated in the International Energy Transition Exhibition, organised in October 2022 by the Tunisian Photovoltaic Trade Union Chamber (CSPT), which counts TuNur as a member.

The association came with the intention of “identifying new business opportunities” while “cutting down on legislative, administrative and financial barriers to the sector’s development”. Ali Kanzari believes that “the 2015 law is not sufficiently conducive to export. That should be the focus.”

The Mediterranean, an energy bridge 2.0

Curiously enough, the cable-laying work allowing the export of electricity is outpacing the solar power plants’ construction. The recent global context has kick-started the interconnection project between Italy and Tunisia, El Med, which has been under negotiation for years. “The feasibility studies will be ready by the end of November, and part of the funding has already been secured,” said Ezzedine Khalfallah, energy consultant for the World Bank in Tunisia, who is working on the interconnection project. According to the Tunisian Ministry of Energy, the project is expected to be operational by 2027.

The objective is to create “a bridge between Europe and North Africa via a Euro-Mediterranean interconnection system…allowing for an exchange of electricity between the different markets,” as stated in the draft law approved by the Italian Senate in April 2021 regarding “the ratification of an agreement between Italy and Tunisia on the maximisation of energy exchanges between Europe and North Africa.

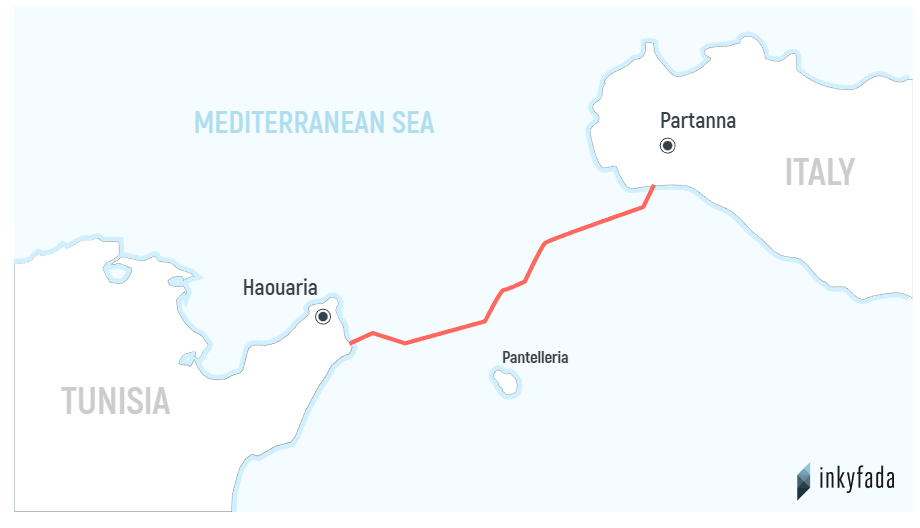

The 800 million euro project, led by the State-owned company STEG and its Italian counterpart TERNA, entails the construction of a 200-kilometre submarine cable between Kelibia (Cap Bon) and Partanna (Sicily), with a power capacity of 400 MW. After a financing of $12.5 million for technical studies, according to the World Bank consultant, the international financial institution is prepared to bear the construction costs for the Tunisian part. Tunisia has also applied for funding from the European Commission in September.

While the electricity exported by El Med will pass through the Tunisian national grid, TuNur intends to build its own cable connecting the southern Tunisian power plant to the town of Tazarka, in north-western Tunisia, which is itself connected to Montalto de Castro, a small town near Rome. A source close to the matter also referred to the possibility that the project would use the El Med line which, in terms of its current design, would not have the capacity to support the 4.5 GWh produced by TuNur.

Tunisia is by no means the only North African country to consider electrical interconnection with Europe. These past few months have witnessed a surge in announcements about the construction of electricity interconnection cables between both sides of the Mediterranean. In Morocco, the British company Xlinks has announced the construction of the world’s longest submarine cable network – 3,800 km – by 2027 and the installation of a 10.5 GWh solar power plant to supply electricity to 7 million British homes, covering 8 percent of the country’s electricity needs. In an effort to become an energy hub between Europe, Africa and the Middle East, Egypt has started the construction of a maritime electricity interconnection line with Cyprus and Greece. Algeria has also proposed to supply Italy and part of Europe with clean electricity via a new submarine cable.

Today, there are growing calls for a just energy transition that doesn’t interfere with the Mediterranean’s environmental and social imperatives. Several unions and organisations are advocating a more decentralised model of green energy production, through which citizens would be in control of the energy they consume. “Another energy transition model is possible.” As the international community meets for COP27, the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETP) are likely to be the central focus of these climate negotiations.

IMS’ reader on environment in the MENA region

The pieces published here tell the story of the way the environment has been understood and questioned by our partners in the MENA region.