As a consequence of the torture she endured during childbirth, Cristina had suffered from prolapsed uterus for four years.

(Photo: Gustavo Torrijos)

Obstetric violence: untold horrors at the hands of the paramilitary in Santander

A group of men who were part of the Central Bolívar Bloc seized control of the village of Cincelada and “played” doctors to torture a woman during childbirth. It’s been 17 years and she is still suffering from physical and emotional consequences. Her testimony may be added to macro-case 08, opened by the JEP.

By Cindy A. Morales Castillo

In her memories, Cristina* can’t separate the pain of giving birth from the agony of torture. On top of the pain of labour, she will forever carry the suffering inflicted on her by members of the paramilitary on that Tuesday in April 2005, which has led to 17 years of non-stop physical pain, among other issues.

Going back to that day disgusts her, in part because of the impunity that her case has met before every single court where she dared tell her story, but also because of the shame. She wonders how five paramilitary men could just “play” doctors while she was trying to give birth, writhing around and bleeding out while her body was ripped apart.

That Tuesday she went down from her rural settlement to Cincelada, a village located in southern Santander, which is famous for being the place of birth of independence heroine Antonia Santos, whose name, in the language of the Guane, means “fearless”, a contradiction to what its inhabitants had experienced.

By then, according to Cristina’s calculations, she had at least 20 more days before reaching week 39 of her pregnancy. However, she went to the healthcare centre as per her doctor’s recommendation, who had already told her at last checkup she needed an authorised referral to be admitted into the hospital of Charalá. “It had been 10 years since my previous pregnancy, so the doctor told me I had to have a C-section but at Cincelada they didn’t have the proper instruments for that. I had to get the authorisation from him early enough,” says Cristina, who was 34 years old back then.

To get to Cincelada from home takes either two and a half hours walking or coming across a vehicle that would happen to go down the narrow path exactly on the same day. Charalá is just 12 kilometres away, but at least four of them are on a tiny, narrow trail of sharp rock and sand path where distances are not marked on big signs but written over literally any piece of available rock.

Additionally, Cristina says, she had to leave everything ready for the men who worked at her “little farm,” where she grew yuca, banana trees and corn. “I had to leave everything set and ready for the girl who would be covering me with the tasks that day,” she explains.

Both Cristina and her husband, having been previously informed it was a high-risk pregnancy, would be better to go the hospital well in advance, so they did that fateful Tuesday when they arrived to the healthcare centre. “I really believe it was a question of bad luck because when I arrived there was another pregnant woman. They said they would throw us both into the ambulance straight to Charalá,but they finally decided to send her there and leave me at the hospital,” Cristina narrates.

The nurse who had taken care of her during her other few prenatal checkups wasn’t there and nobody would say if she was to be transferred to another village or be kept there. However, an order had been given that neither she nor her husband were allowed to leave the healthcare centre.

Harassment at the hands of the “para-men”

Since 1999, the Magdalena Medio had been besieged by paramilitary men from the Communal Front Cacique Guanentá (FCCG), part of the Central Bolívar Bloc. It has been widely substantiated in many court judgments that those self-defence groups recruited minors and besieged the people while authorities simply facilitated or closed their eyes to it.

The most infamous of these abuse cases, which shocked the whole country, happened in Riachuelo, another village in Charalá, where the Communal Front Cacique Guanentá had its military base, just 47 minutes away from Cincelada. There, Lucila Inés Gutiérrez, headmistress of a school in Riachuelo, and her husband, ex-councilman for Charalá Luis Moreno Ocampo, supported the paramilitary in kidnapping, torturing and sexually abusing the school’s students.

“Not only had the couple been organising exhibitions and beauty contests since 2001, but they also offered their own home to keep and torture those kidnapped and allowed paramilitary leaders to enter the school to choose the young women and girls they wanted to rape and keep as sex slaves,” states the grassroots volume of the Truth Commission (CEV)’s final report, citing the court ruling by Justice and Peace dated 11 August 2017.

According to Justice and Peace, the same paramilitary group established a training school in 2002 that didn’t last long and had at least 70 members. It was located in the La Mina settlement, in the village of Pueblo Viejo, in the Municipality of Coromoro, governed by mayor Rubén Darío Martínez Cáceres. As stated in the Single Registry of Victims, at least 32,446 people were victims of sexual violence during the armed conflict. The number of girls and women amounting to 92.5 percent, which proves how their bodies were used as another weapon during conflict. The report on gender by the CEV gathers the testimonies of 10,864 women, whose abusers were members of the guerrillas, the paramilitary and the Public Forces. The document accounts for all kinds of violence: sexual and reproductive.

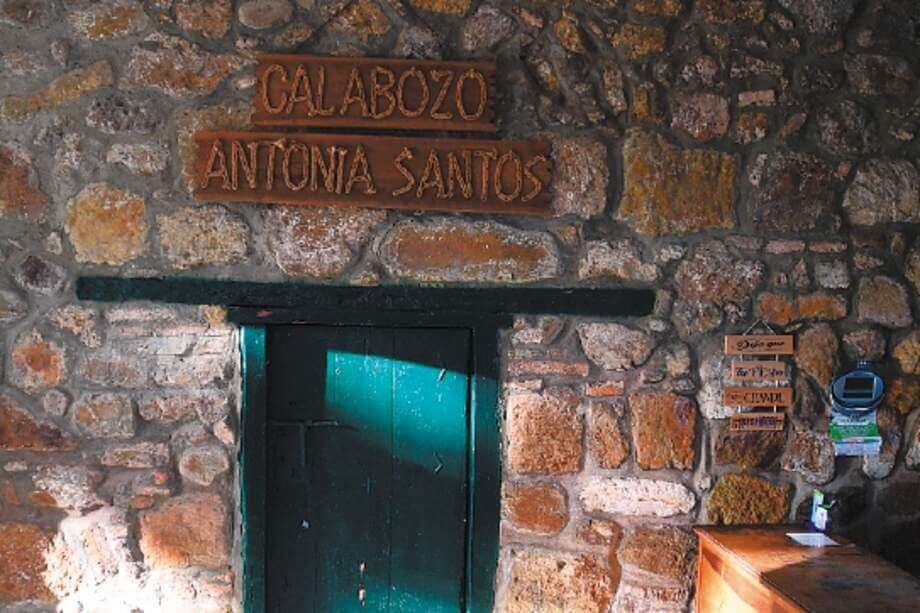

Photo: Gustavo Torrijos

“It felt like having my guts ripped out”

Cristina, as well as the almost 5,500 people living in the village (all settlements and the head of the municipality included), were aware how powerful the paramilitary was and had even become used to it. Rodolfo Maya, president of the Association for the Victims from Coromoro and a member of the Council of Victims of that municipality, explains: “This wasn’t a simple occupation, but absolute territorial control. Just remember that the city hall – that is now a police substation – was the trench of Luz Marina Eslava. She was simultaneously a police inspector and a member of the paramilitary.”

According to a Justice and Peace’s court ruling in 2017, Eslava was involved in the paramilitary organisation known as Yoli. As a police inspector, she kidnapped and tortured farmers and rural people who were accused of collaborating with the guerrillas. She kept them in one of the cells in the station that, in a twisted contradiction in this unpredictable country’s history, was named: Antonia Santos.

And there’s more: for example, the case of Javier Rincón. He was a 15-year-old boy who was recruited under the false promise that he’d be hired as driver. Her mother managed to get him out of the armed group and send him away but, as stated in the court ruling, he was murdered one day before he was meant to return. Just as they took control of the police station, they did with the healthcare centre, which back then was a single story facility with four doctor’s offices and a makeshift waiting room with ten chairs set in two rows. The order not to let Cristina leave the building was given by five paramilitary men who, maybe just for fun or because they were thirsty for power, decided to take on the doctors’ role.

“I wasn’t suffering birth pains because I wasn’t due yet, so they ordered to induce my labour.”

In the absence of the nurse who had been caring for her during checkups, Cristina was left in the hands of a women doctor whose name she does not remember and her assistant. Both women followed every single absurd command given by those men.

“I wasn’t suffering birth pains because I wasn’t due yet, so they ordered to induce my labour. I remember it crystal clear, because they had me have a Pitocin injection (a medicine to start or strengthen uterine contractions). I honestly wish nobody has to go through such amount of pain. And then they told me to push but my baby wouldn’t come out. Within less than two hours, they decided to give me another shot. The actions were obediently carried out by the doctor, but under the paramilitary strict orders,” she explains.

Outside, her husband was getting impatient. He told the men he didn’t understand what was happening, he could only hear Cristina’s screams. He asked – or should I better say that he, acting as a protective father – demanded that they let him take his wife to the other hospital. “He was pretty emboldened after hearing my tortured screams, but they told him I couldn’t leave and that it’d be better for him if he kept quiet because, should he keep nagging them, they’d tie him up. What could he do? He shut up and waited to see what happened…I think they didn’t want us to tell anyone that they had taken over the hospital,” Cristina says. Before this baby, she had already been through other three childbirths: two accompanied by a midwife and a third one at the hospital in Charalá. “My other labours were normal; no drugs or anything. Natural, normal births. That’s why I say this one was really traumatic,” she states.

The paramilitary men ordered the doctor to do whatever was necessary to get the baby out.

Quite right, too. The medicine was doing its job and the contractions were getting stronger and stronger, like she had never felt before in previous labours. And the nightmare wasn’t over. The paramilitary men ordered the doctor to do whatever was necessary to get the baby out. “She stuck both hands in me to pull the baby out. The agony was unbearable. It felt like my guts were being ripped out. Then, she demanded: ‘Come on, push, you have to spit the baby out,’ but it was impossible. Then I was dropped on a stretcher and I started to bleed out so they threw water on me. Not to clean me: they were throwing buckets of cold water on me. The world started spinning around me and the last thing I saw was them getting me another injection to revive me,” Cristina narrates.

“I’m lucky my husband is 20 years older than me and since he’s not so young anymore he’s not that active. Otherwise, he would have left me. He would have said I was cheating or that I didn’t love him anymore. The truth is I didn’t want to do anything at all.”

Victims of obstetric violence at the hands of paramilitary men

When the men realised that the situation was out of control, they called for an ambulance. Cristina says she heard them say that they’d both probably die (she and her baby). “I think God guided me at that moment. I realised I had only two alternatives: die or run away. So I jumped off the stretcher, I slipped and I have barely managed to walk three steps when the baby fell to the floor. Suddenly, the doctor came back and started scolding me. They picked my boy up and threw water onto him. It was such terrible torture,” explains Cristina. She pauses as digging deep into her memories, maybe to clutch onto them with her rough and overworked hands, tireless instruments used for ploughing the land. The atrocities she’s narrating are barely audible and in a very tiny voice she mumbles that she can’t understand: why her?

Photo: Gustavo Torrijos

“I’ve been living in pain for 17 years”

The baby was born and today he is a healthy young boy, but Cristina’s personal tragedy wasn’t over. The pain she endured the days following delivery was almost as awful as it had been during labour. “It felt like a never-ending torture. I suffered from intense vaginal pain, I had lots of discharge and I felt more and more sick day after day. I had to go back to the healthcare centre, but I only did it once my nurse was back,” she says.

As soon as she saw her, Cristina remembers, the nurse was shocked: “She kept asking me again and again what they had done to me and kept telling me if she had been there, she wouldn’t have let them do it,” she asserts. The nurse’s diagnosis was very discouraging. Cristina’s uterus had come loose, as another doctor confirmed after four years of acute pain. “The doctor said I needed urgent surgery; imagine how long I had been in such agony by then. It had to undergo a month of checkups before surgery. Then, they discovered I had a 12-centimetre tear of my womb,” Cristina says.

During that time, she explains she had been taking birth control injections, she had no periods and was constantly getting infections. On top of that, she suffered from aches in her waist and bladder that have caused her incontinence. “I feel so embarrassed to say this but sometimes I’d discharge disgustingly smelly blood clots. That’s why I had to have surgery. Otherwise, I’d have got cancer,” she states.

Her sex life was also impaired. “It was completely wrecked because I was always in pain,” she explains. Through her next answer shines the sexism women are exposed to. “I’m lucky my husband is 20 years older than me and since he’s not so young anymore he’s not that active. Otherwise, he would have left me. He would have said I was cheating or that I didn’t love him anymore. The truth is I didn’t want to do anything at all,” she says.

The Geneva Conventions state that pregnant women are protected subjects and must be treated with particular respect during armed conflicts. This is reaffirmed in the Convention of Belem do Pará, which specifically mentions that physical, sexual and psychological violence against women may also take place in healthcare facilities. In Colombia, Law No. 1257 of 2008, among other things, governs women’s right to a life free of violence, and the Law of Medical Ethics imposes onto healthcare staff the duty to act immediately in such cases by reporting irregularities to judicial authorities. In the case of Cristina, no one did it.

Several testimonies of other women within the area to this journalist state they didn’t dare go into the healthcare centre nor do any prenatal checkups while the facility was under paramilitary control.

The horror room where Cristina gave birth still exists in the healthcare centre, which is now a two story building. On the day of this interview, she made the most of the visit to the village and scheduled a doctor’s appointment, one in a long series she had to go through due to the physical damage caused by such violence, hoping one day doctors would finally “hit the nail on the head.” She showed us the location of the doctor’s office. The hospital lights don’t reach the place, located at the very end of the building. Inside there’s an OB/GYN stretcher covered by a white half sheet and a device that seems to be an ultrasound machine. It’s a windowless room and a particular smell drifts across the air. “There’s a strange energy in there, don’t you think?” she asks.

In 2016, Riachuelo became a beneficiary to the collective reparation programme after the crimes against humanity perpetrated by the Central Bolívar Bloc were proved true. Almost every crime committed in that municipality was also committed in neighbouring Coromoro and Cincelada. Thus, in the very same year, a petition was brought before the Victim Assistance Unit to achieve collective recognition. The Unit rejected the petition because as stated on resolution Colombia+20 was given access to, there was no way to demonstrate that “the social fabric had been damaged because of the lack of any cohesion element” among the community. Cristina filed her administrative case on the grounds of Law No. 1448 governing victims’ compensation, but it has not been admitted and, therefore, she is not currently included in the Single Registry of Victims. Later, she navigated the process set by the Justice and Peace Act (which aimed at demobilising paramilitary groups), with no luck so far. Her last hope lies with the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), where she testified for a report. There’s a chance that this Special Jurisdiction for Peace will include her case in the recently opened macro-case 08, which will investigate alliances between the paramilitary, the Public Forces and civilian third parties. “I hope this one would succeed because this is the last time I tell the story,” she concludes sharply.

*The story featured in this article belongs to a Santander woman leader who, for safety reasons, has chosen not to disclose her name.

**The name of the protagonist has been changed for safety reasons.

***This text is one of several journalistic articles about women social leaders from Santander, Córdoba, Sucre, and Cundinamarca in the context of IMS’ project “Implementing Resolution 1325 through media,” in association with the Alliance Initiative of Colombian Women for Peace and supported by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.

Cindy A. Morales Castillo is the General Editor of the Colombia+20 project at El Espectador.

This article was originally published 12 September 2022 in El Espectador. Read the original here.

Navigating a changing world: Media´s gendered prism

IMS media reader on gender and sexuality