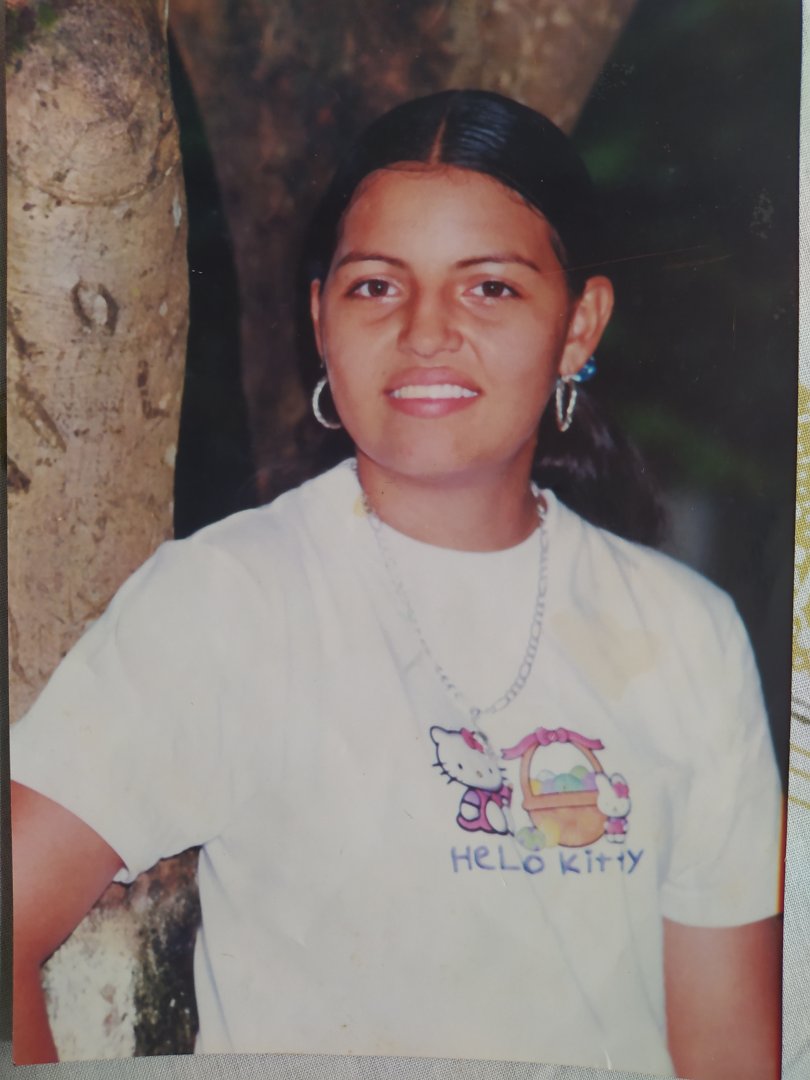

Lorena Yadira Nieto Criollo was seen for the last time at the age of 14.

“This is how the errand was done”

The armed conflict in Colombia – between governmental armed forces, aided by self-defense groups, and the FARC (the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) – was fraught with massive and systematic violations of international human rights and humanitarian law.

Forced disappearances constitute one of the worst practices of the combatants. The peace agreement signed with the FARC created a special body to search for the disappeared. Most official and media narratives only told the story of men. Through the case of a young girl in the Eastern Plains, one of the war’s epicenters, a local reporter delves into the women’s fates.

This is a story about the undocumented and enforced disappearance of women in Colombia’s Eastern Plains and a story of the women who build peace in the territories.

By Carolina Tejada Sánchez

“Goodbye, I’m leaving, I’m leaving tomorrow!”

Lorena was happy when she said goodbye to her teachers at the high school Colegio Los Centauros, in the municipality of Vistahermosa, department of Meta. The next day she would leave for Villavicencio, where her aunt Doris, whom she looked so much alike, with her long black hair, was waiting for her. Her destination would be Bogotá, where she would meet her mother Cirleny, whom she had already notified that she wanted to leave town. Very early on the morning of 22 September 2002, she left the room where she lived, carrying only a suitcase and dressed in her plaid uniform. At the stop, she boarded a bus of the fleet of La Macarena company, heading for Villavicencio, the capital of the Eastern Plains.

The trip would last three hours and, as was customary, there would be military checkpoints along the road. Several armed groups were present in the area, and violence was very frequent. Thus, the words of her mother when saying goodbye by phone:

“Be careful. May God take care of you on the way.”

The days passed, and Lorena never reached her destination. When her mother and aunt inquired about her, they were told that they she was seen for the last time at the bus stop.

“What happened to the girl?” the schoolteachers asked with anguish.

“Nobody knows anything,” Cirleny used to answer.

Since Lorena was born, her aunt and her mother took care of her, Doris remembered while reviewing photographs of Lorena in the dance dresses and costumes that she made for her. Lorena’s smile lit up her face from ear to ear in the images. “She was always a very happy and friendly girl,” said Doris.

Lorena Yadira Nieto Criollo, seen for the last time at the age of 14, is one of the many women and girls who disappeared in the middle of the armed conflict in the Eastern Plains. There is little documentation around cases like Lorena’s, as if they were minor issues. Only some records prepared by human rights organisations and newsletters of the government of Meta reported figures for the department, without a differentiated approach, without major warnings. Not until the third bulletin of forced disappearances in the department of Meta, a publication covering 1984 to 2018, was it reported that 14,157 people were victims of forced disappearance, of which 6,854 were women, and that this phenomenon had peaked in the years 2001, with a figure of 1,028 disappearances, in 2002 with 1,357, and, in 2003 with 1,369, the highest figure to date.

The bulletin also recorded that, between 2000 and 2018, there were more victims between the ages of 29 and 60 – 8,278 – than all other age groups combined: 2,694 aged between 61-100 years; 1,803 aged between 18-28 years; and there were about 330 victims aged 12-17 years. These are just cases in one region; in the country as a whole, there were about 80,000 victims between 1970 and August 2018, according to the registry of the Observatory for Memory and Conflict of the National Center for Historical Memory (CNMH).

The municipality of Vistahermosa in Meta is the one with the highest rate of forced disappearances, with 2,328 cases. The peak of cases of missing women in the department was in 2002, with 670 cases. Still, this is only the official record. The overwhelming shortage of information about this reality was the reason for my trip to the Eastern Plains. I was interested not only in knowing the figures, but it was also important to me to know the details of who these women were and what had happened to them.

Walking the steps

Three hours from the cold of Bogotá and under the high temperatures of Portón Llanero – a road to enter the Eastern Plains – the search began. I met with Vilma Gutiérrez, the coordinator of the Movement of Victims of State Crimes of Meta, an organisation that works to end impunity in cases of forced disappearances, extrajudicial executions and selective murders. The first thing Vilma warned me was that this task would not be easy.

Most of the disappeared were not reported and, when their relatives did report, hardly kept a photo. In an office full of folders that she cared for like a treasure, Vilma had what she called “the memory gallery” with a photograph of each of the disappeared pasted on cardboard and a small caption.

Most of the disappeared were not reported and, when their relatives did report, the families hardly kept a photo. In an office full of folders that she cared for like a treasure, Vilma had what she called “the memory gallery”, with a photograph of each of the disappeared pasted on cardboard and a small caption.

Most of the entries had a flower instead a photo. I asked her why and she said: “because there are no photos and the way to represent them is with a flower”. She shared a file with each of the cases she had registered so far: Gladys Orfilia Sarmiento Pardo, Sonia Patricia Vera Sarmiento, Ermelinda Pabón Sarmiento, with a red rose and her personal history, Alba María Álvarez Mancera, a peasant woman, with a yellow rose, and many, many more. Many of them were social leaders.

The next morning, I entered the intense plain. In Vistahermosa, I met with a woman whom we will call María, a member of a group of searchers, who would accompany me on a tour of the region [her name has been changed changed on her request. There are well-founded fears about the risk assumed by people who report cases of enforced disappearance in the region. Some of the armed groups allegedly involved in the disappearances are still active in the area]. With Maria, we fulfilled the schedule for the first day of my reporting work and, late at night, she left.

I got ready to wait for Doris, Lorena’s aunt, in the front yard of a humble house built on rubble, owned by one of the mothers who search for the disappeared. When I called her on her cell phone, Doris asked me:

“Are you the one in the truck?”

I said yes.

“I didn’t go near, because you never know,” she said. She had passed by minutes before on her bike. Her precaution was normal due to the public order situation.

“There is fighting, six soldiers died.” “Yesterday they killed two leaders of a nearby municipality”, residents of the area warned me. One could smell the fear. The war in Vistahermosa had not ended with the signing of the peace agreement.

After greeting Doris, she simply said “we already met”. We agreed that we would meet very early the next day, and she left.

Yesterday’s war, today’s fears

The fear of the people was understandable. They did not want to return to those times in which the armed conflict deepened. According to retired army general Jorge Enrique Mora Rangel, the security policy during the two terms of former President Álvaro Uribe Vélez, entitled “democratic security”, and the Patriot Plan had “bent the will to fight of the narco-terrorist groups”, referring to the Farc.

During that time, the civilian population suffered greatly under bombings, kidnappings, displacement and forced disappearances. Paramilitarism strengthened and, as Mora Rangel described it, the guerrillas weakened. Nonetheless, the practices of the national army on the ground were the object of strong denunciations.

In the midst of the whirlwind of the armed conflict, the disappearances of civilians soared. This was denounced during the public hearing called “humanitarian crisis in the Eastern Plains”, held in Macarena, on 22 July 2010, organised by the peace commission of the Senate, as proposed by senators Iván Cepeda and Gloria Inés Ramírez, at the request of the communities and organisations that defend human rights.

In the savannahs of the Eastern Plains, between 2010 and 2012, the Office of the Attorney General reported the discovery of 2,304 unidentified bodies and, of these, 1,674 were counted as casualties of combat. In 2018, 899 bodies were identified as victims of extrajudicial executions. According to a report by the Group for the Search, Identification and Return of the Remains of Disappeared Persons of the Prosecutor’s Office (GRUBE) in this same region, dated 30 June 2020, 1,667 exhumations were documented, with 899 bodies identified and 280 delivered to next of kin.

According to the Ministry of the Interior in its report for the period January to December 2018, 30,750 bodies of unidentified people were accounted for in 426 cemeteries. Five of these cemeteries are in the Eastern Plains: Villavicencio, Granada, Vistahermosa, La Macarena and San José del Guaviare.

At the beginning of this year, a photograph was taken of a woman with a sad and lost look, holding a poster reading: “I would have hugged you so hard if I had known that it was the last time I was going to do it.” The woman was collecting the body of a relative, many years after their disappearance in the village of San Isidro, municipality of Mesetas in Meta. After the Macarena public hearing, theirs was one of the many remains that had been identified and handed over for a Christian burial. The search for missing women in the context of the armed conflict was the reason for my meeting with Doris, Lorena’s aunt.

Before seven in the morning, Doris arrived at my hotel on her bicycle. She had a small bag, some papers and a long memory. On the mattress in my room, the camera was turned off at her request, and she began to tell me: “My daughter was disappeared on 22 September 2002”, referring to Lorena, her niece. “She was studying here at Colegio Los Centauros. She was very cheerful. The teachers told me that the day before, she happily said goodbye, “bye, I’m leaving, I’m leaving tomorrow!” The next day she got on a bus with her suitcase, with a uniform and everything. She went to where I was”.

Lorena had been to Villavo [short for “Villavicencio”] before with her aunt but decided to return to study to Vistahermosa. “I told her, ‘Mamita, don’t go to Vistahermosa again!’ However, she went back. Her father was there, but he never answered for her. Lorena wanted to study there and for that she could stay with my brother. There, in Charco Azul, was where some men who were riding a motorcycle got off and took her away.” According to a witness to the events, the two men introduced themselves as Farc guerrillas.

In the midst of their inquiries, Lorena’s aunt and mother learned that Lorena lived in a room paid for by a military man, with whom she allegedly had a relationship. For these women, Lorena’s disappearance had a lot to do with the military. Her disappearance was filed in Villavicencio and at the prosecutor’s office in the locality of Kennedy in Bogotá.

While Lorena’s aunt spoke to me about her niece, she remembered the words of a mother from the 13th commune of Medellín, when explaining the Stations of the Cross [an expression which means “the ordeal”] to her in the search for her youngest daughter who disappeared during Operation Orion: “I told the media: ‘my daughter is not lost, my daughter was disappeared.’ This clarification had to be made frequently. In the context of the armed conflict, people did not get lost, or go missing, like on their way home, right?” [Orion, a military operation that took place on 16-17 October 2002 in one of the most violent neighbourhoods of Medellin, is considered one of the pinnacles of former President Alvaro Uribe’s policy of “democratic security”. In the search for urban militias of the guerrillas FARC and ELN, the Colombian army committed massive human rights violations, including a still unconfirmed number of disappearances, estimated to reach almost a hundred.]

In Colombia, despite the fact that the Constitution states in Article 12 that “no one shall be subjected to forced disappearance, torture or cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment or punishment”, these types of human rights violations are frequent. The Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons, in Articles 2 and 3, defines forced disappearance as: “…the deprivation of liberty of one or more persons, whatever its form, committed by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorisation, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a lack of information or the refusal to acknowledge said deprivation of liberty or to report on the whereabouts of the person, thereby preventing the exercise of legal means and the pertinent procedural guarantees.”

In Colombia, the first of these cases was that of a left-wing militant Omaira Montoya, detained by the secret police on 9 September 1977. It was only in 2000, under Law 589, that this was classified as an autonomous crime.

Despite this classification, not everything is documented, the whole truth has not been unearthed and only women who form collectives to search for their loved ones continue to seek information.

When we moved around the municipality, Maria was constantly shaking my arm, saying, “There goes so-and-so, she is also looking for her daughter.”

Where are they? To speak of these crimes is to inquire into a cover-up about who was kidnapped, detained or captured. In the municipalities of Eastern Plains, these cases are overwhelming.

The silent witness

Along an uncovered sapote-coloured road, surrounded by green savannah and under a hot sun, we went to one of the places where, according to information, the bodies of people who had died during the armed conflict were buried. This site had not been excavated, as in Vistahermosa, where they unearthed more than 70 nonidentified bodies of men, women and children, thanks to the process following the Macarena hearing. This was the Piñalito cemetery. There was not much documentation on this burial ground so the task was to know the situation first-hand and have an interview on the spot.

As we walked along the highway, I commented that the reports that I had reviewed on enforced disappearances did not accurately account for the cases of women. The few that were registered are mentioned as “missing women without information.”

“Yes, not all of them have that luck,” María declared with great confidence to which I responded with a look of surprise. “Not all the disappeared are sought,” she said, referring to Lorena’s “luck”.

A sentry box, some trenches, a couple of barricades and a roadblock lying on the side of the road announced that we had arrived at the national police base at the entrance of the Piñalito village. There was no one, and we passed without a problem on our way to the cemetery.

Upon arrival, we found a small open gate and the gaze of a herd of cows that watched our entrance. The sun was shining on the abandoned graves, many without even a name or a number. In the back to the left there was a small but visible mountain of disturbed earth with a cross made of stakes.

“There are many unidentified bodies here; the problem is knowing exactly where they were buried because many times they don’t even put a cross on them,” said María. After walking and observing the place – approximately half a hectare of land with thick undergrowth and shrubs typical of the savannah, fenced with barbed wire – we left under the midday sun with more questions.

“Stop, stop. There is Doña Gloria,” said María. A woman was at a table by a corner store next to the entrance of the bridge, doing chores with some children. The two women knew each other. As we got closer, I could hear from a small television set the sound of a harp and the voice of Julio Miranda:

“She was

the woman that I loved the most

the one that planted her roots

inside my heart

but today

from my side she has left

and I live desperate

longing for her return

and wishing for her warmth.”

After greetings and buying some bottles of water, I asked for the bathroom. “At the bottom to the right,” the lady replied. On the way to the bathroom, in the middle of the darkness, I saw a hole in the floor and a staircase that, despite the low light, I noticed went down to a room. The mysterious place reminded me of Cold War movies in which basements were common places to hide Jews from the Nazis.

I did not hesitate to ask: “Doña Gloria, do you have a basement?”

“Yes ma’am,” she answered.

I had not managed to continue with my questions when María said: “She’s a journalist and she is doing a report on missing women.”

Immediately, the lady’s face changed; she raised her head from the workbook and looked at me with misgivings. The silence seemed eternal. I drank some water and, seeking her cooperation, I explained that I understood her objections about the role of the press covering issues of the conflict.

She said: “It is very important to know the truth about the disappearance of so many women.” Minutes later, the children abandoned their tasks and, with Doña Gloria on the bridge over the Güejar river, the camera began recording the women’s stories.

She pointed to the wooden boards that hung from some irons; she said with regret that the apogee of the war began in the year 2000. That bridge had been a silent witness: “Illegal armed groups arrived and executed people and threw them into the river, or they brought the corpses in bags, already dismembered, and put them right here.”

Those who lived in the village pulled the corpses from the river when they could: “They would take them out in the dump truck and buried them here, as NN [nonidentified],” she said, referring to the cemetery.

Doña Gloria recalled that, during 2003 and 2004, she saw around 1,500 people pass by from her home, carried by armed actors over the bridge. “The victims went ahead, the perpetrators behind, as if herding cattle… There were pregnant women, women of all ages and social classes, even the leader of the community board.” Her name was Blanca, there was no legal report of her disappearance, because her family has the illusion that she will return. There was also Esperanza and a girl “whom we called ‘the hairy one’ and so many more.”

There is still an abandoned casa de pique [torture house]. In 2000, that was the place where the paramilitary groups that were unified in the Bloque Centauros of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, Frente Hernán Troncoso, imposed the practices of dismemberment and forced disappearance. On the other side of the bridge, the Eastern Bloc of Farc was present. The fighting between these groups and the army was the main reason, Doña Gloria says, for the construction of basements in each house. It was the way that families could save their lives. “Those who had a basement could save themselves from the bullets.”

She can no longer remember many names. “About the disappearances of women at that time, even today, nothing is known, no one has confessed, nor has the truth been found about where they are. It is very important, as women, to demand that the truth be known,” reiterates Doña Gloria. She calls on the formerly armed groups to take advantage of the possibility provided by the peace agreement to tell the truth. As a result of that tragedy, the bridge was the object of collective memorial: “We wanted, in memory to the victims, and in symbolic atonement, to call it the Bridge Tribute to the Victims of Heliconias of Peace.”

When we were leaving, on our way to Vistahermosa, I asked why the police base was empty, to which they all replied: “Well, because the guerrillas must be there.” The driver of the car said: “it’s late, we better go” and sped up.

Did the plains eat the women?

What happened to the women who were victims of violence? The question remained in the air, even after several trips in the savannahs. Doris, Lorena’s aunt, replied:

“Women were never found, only the men were found, the women they killed or took away never appeared.”

Weeks before leaving Bogotá, I had sent several questions to the municipal authorities of Granada, Vistahermosa, La Macarena and San José del Guaviare. I wanted to know new figures of cases that had been registered of forced disappearances since 2000. Before returning to Bogotá, I sought to speak with the local ombudsman: “He is very busy,” his secretary informed me. Days later, I was notified by email: “…when this office finds out about these facts…it makes a statement” and, once it is received, “it is sent to the Unit for Comprehensive Attention and Reparation of Victims…The information received by the municipal ombudsman has security and confidentiality restrictions.” It was signed by the municipal representative.

The ombudsman of San José del Guaviare replied that there was no such information; however, he “sent the request to the Guaviare Sectional Prosecutor’s Office” and attached the response of the entity. The Excel file they sent me belonged to the “forced displacement” cases. Among several cases in Guaviare was that of Zuli Camelo Buzato, a woman who was disappeared from the village of Charras during fighting between paramilitary groups and the Farc guerrillas on 18 September 2002. She worked in a drugstore, had a 9-year-old and was eight months pregnant. After an armed confrontation, her whereabouts and those of four other women were never known. Her mother, Doña Amparo Buzato, has documented her story in “a memory notebook” and has acted as a detective in the search for her daughter. On five occasions, she inspected, in the company of various state entities, the place where witnesses said that the remains of her “gordita” could be found, but never were.

The insufficient information given to me led me to think that these entities had never systematised the information or simply refused to deliver it.

I said goodbye to María in the Vistahermosa cemetery after we visited the place where more than 70 unidentified bodies had been unearthed. The pits were still visible.

Back in Villavicencio, I had a feeling of uncertainty. Surely, we had gone through the place where Lorena was taken. Without registration, it is not known how many more women are missing. In Villavo, I looked for Deitania, who works in the non-governmental organisation Orlando Fals Borda Legal Collective, dedicated to accompanying the families of the victims of forced disappearance in the region. “The Covid collective,” I called them, since almost the entire team was coming out of quarantine.

With the anguish that I was carrying, I said: “Tell me something, you have so many cases of disappearances, why are there almost no records of the women?”

Deidania replied: “Usually, there is only talk about missing men. And we know that great violence has taken place against women just because they are women. There are no reports because the partner or the husband does not have enough time to file a complaint, so that’s why many cases remain unreported.”

When a woman disappears, she continues, “It is thought that she has left, so she is not reported or there is no one to go and file the report. Women are the ones who lead the household and if she disappears there is no one to file the report.”

Deidania, who has travelled through several municipalities documenting cases, noted: “In our experience of the documentation, there are many women, who before the disappearance, were also tortured and raped, but that is not mentioned in the report.”

Who gave the order?

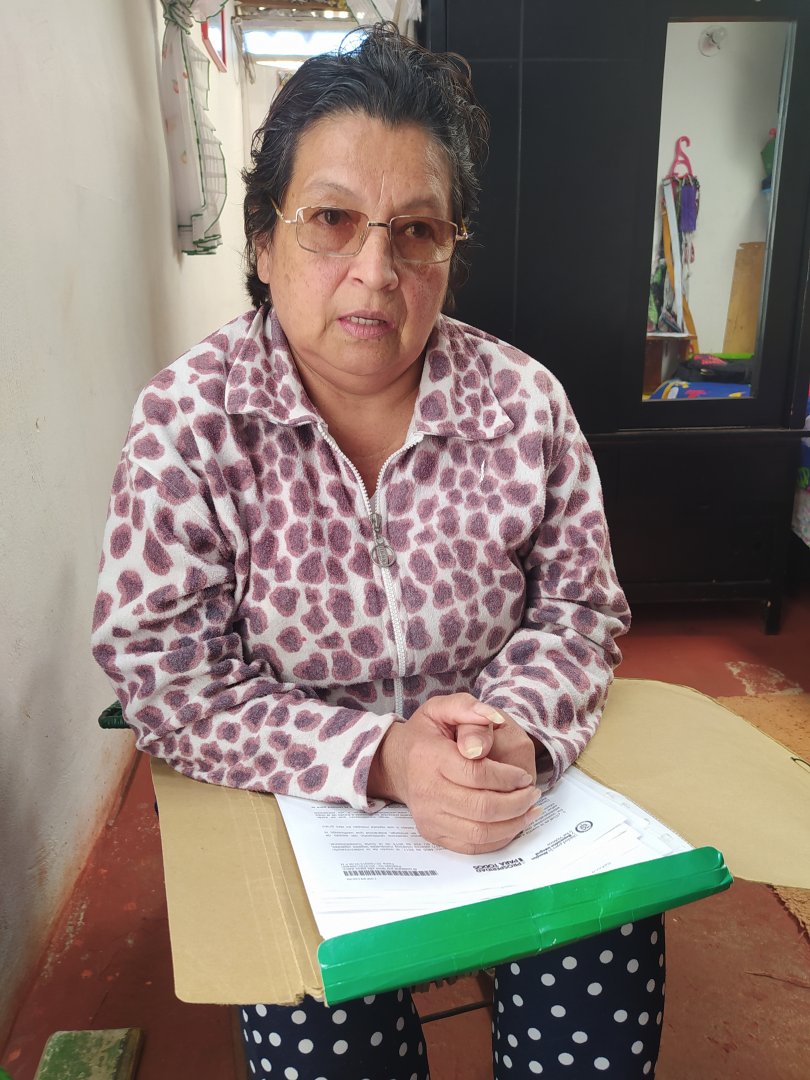

Days before, Lorena’s Aunt Doris had told me that there were witnesses. A hearing was held, and Lorena’s mother Cirleny had been there. When I got to Bogotá, I looked for Doña Cirleny Criollo. She was waiting for me in the south of the city, in one of the many mountains in the capital, in a small house such as the ones given by the government as reparation to victims. She invited me to come in and took out several folders from a closet. “This is from our other daughter,” she said.

She had already lost her eldest daughter in the war. She showed me several reports that she had made in Bogotá and other documents that she had brought from Villavicencio: “I also have an agenda where I wrote was said at the hearing,” a space that was convened by the 59th Prosecutor’s Office, specialised in international human rights and humanitarian law of Villavicencio in July 2013.

As she searched for the notes, she remembered that her daughter had called her days before:

“When Lorena called me, she said: ‘Mom, I’m going, I’m bored!’ I asked her why, and she said: ‘No, Mom, I’m going!’, I said ‘well, better come. Be careful,’ I said ‘and may God take care of you on the way.’”

Cirleny flipped through the old diary with several entries and began to read:

“This is how the errand was done. She was traveling with Felipe to Villavicencio in the La Macarena fleet. When they left the municipality of Vistahermosa, kilometres later, they were both brought down. This was planned with Commander Chatarro. The order was given to the four of them to disappear her.”

They were not Farc guerrillas, they were paramilitaries. After a long process, they went through a hearing in which they were questioned about Lorena. The first paramilitary, alias Felipe, denied knowing her. But a second man confessed and recounted the details of how he had done it. Doña Cirleny went to that hearing, but she was scared, so she wore a cap so they wouldn’t recognise her.

From that hearing, she obtained this story that she managed to transcribe in her agenda. She took a breath and read:

“‘When they got Lorena off the bus, Víctor and I were pretending to be the Farc,’ said one of the paramilitaries, ‘…others were waiting for us, Caney was waiting for us; where we would put the victim had been decided and planned eight days before. The order was carried out. There were the four of us, me, Felipe, Víctor ‘el Loco’, Caney Arias and Alberto ‘el Perro’ Llanos; we carried weapons, but not uniforms.’” She breathed again and continued: “Caney and Víctor ‘el Loco’, we were guarding her, the victim did not speak.’ A girl helped me copy,” she said, and continued: “‘Felipe’s role was to kill her, and he cut her throat with a razor. The role of Alberto Llanos was to dig the hole to bury her. They cut off her legs from the groin so as not to make the hole so big.’”

According to a certificate from specialised Prosecutor 61, on 6 September 2013, Daniel Rendón Herrera, alias Don Mario, Manuel de Jesús Piraban, alias Don Jorge, Luis Alex Arango Cárdenas, alias Chatarro, and Alberto Antonio Llanos Serrano, alias el Perro, all members of the self-defence groups, were convicted by a judge for the crimes of forced disappearance and homicide of Lorena Nieto Criollo, and Juan Esteban San Martin, aliases Sergio or Pipe, was awaiting a sentence.

To find Lorena’s body, a commission was set up with the Prosecutor’s Office and one of the men who confessed and was responsible for digging the hole to bury her. The order to kill her and hide her body was given by paramilitary commanders, according to the convicts. Doña Cirleny, with the same force that she read the confession notes of the paramilitaries, told me:

“What I demand is that they look for her to give her a Christian burial. I just need that…”

Her voice trailed off. She lowered her gaze on the notes, while she dried her tears, and I understood that the search commission never found Lorena’s body. That’s why her mother said:

“I am demanding that they find the girl’s body and not that they give me the wrong one. May I give her a Christian burial and know that I have a place to visit her. I always told her ‘I’ll never leave you alone, I’ll always be with you until the end.’”

The article was originally published 25 November 2020 by Consejo de Redacción. Read the original here.

Navigating a changing world: Media´s gendered prism

IMS media reader on gender and sexuality