Sonia Terrab.

Moroccan “outlaws” win women’s freedom prize

Yesterday, Sonia Terrab and her two project partners, author Leila Slimani and human rights advocate Karima Nadir, received the Simone de Beauvoir Prize for women’s freedom 2020 as representatives of the Moroccan women’s movement Collective 490. This is an extraordinary story of the power of women’s solidarity and media to create change

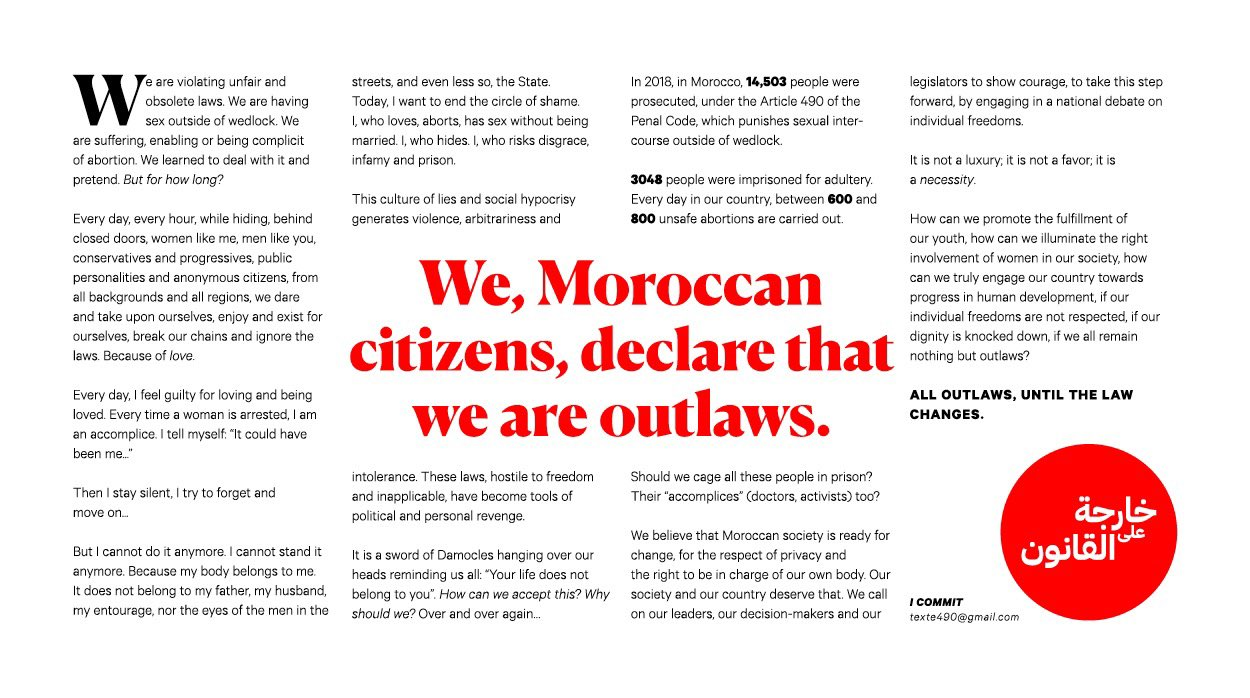

“We, Moroccan citizens, declare that we are outlaws.” These words headlined a manifesto that started circulating on social media at 10 in the morning of Monday 23 September 2019. The same statement made the front page of the French newspaper Le Monde. The manifesto encouraged Moroccans to commit to its cause: to sign a petition to abolish Article 490 of the penal code that punishes sexual intercourse outside of wedlock.

490 women signed the petition almost immediately and publicly declared that they were violating the laws by having relationships, engaging in sexual relations and supporting abortion. Today, this number has reached 15,000. And so, the Moroccan women’s movement, Collective 490, was born.

The event that triggered the movement was the arrest of the Moroccan journalist Hajar Raissouni and her partner Rifaat al-Amin as they were leaving a gynaecologist’s office in the capital Rabat. They were charged with having sex outside of marriage and an abortion, and the doctor, dr. Mohammed Jamal Belkeziz, and two members of his staff were later arrested on the charges of performing the abortion. The couple and the medical team denied the abortion, but explained that the operation was an emergent procedure to stop an internal bleeding. Not long after, Hajar Raissouni and her partner were sentenced a year in jail while the doctor received a two-year sentence.

Sonia Terrab, a Moroccan film maker and a long-time partner of IMS documentary film programme, heard the news and was not surprised. Hajar Raissouni worked as a journalist for the independent newspaper Akhbar Al-Yaoum that often were critical of Moroccan authorities. ”Every three months, we have scandals like this one that involves sexual relationships outside of marriage, and we all know it is often politically motivated,” Sonia explains.

This case became the straw that broke the camel’s back for Sonia: “As soon as I heard about Hajar Raissouni I just thought: ‘It’s enough now. Moroccan women need more freedom. This time we’re going to do something about it. We are going to do something big, something massive’.”

Media as fuel for change

From here, the idea for the manifesto ignited. Sonia’s first step was to gather women who shared her outrage: “I started calling some of the bravest women I know who would be willing to speak publicly about defying Article 490.” Leila Slimani, who is an internationally recognised author, was quickly onboard, and together they crafted the manifesto, decided to name themselves outlaws and invited other women to sign the petition – to be precise, they kept calling and writing until they had signatures from 490 women.

“We were surprised at how ready Moroccan women were to stand up for this cause. We just had woman after woman saying: ‘I’ll commit and I want to know what else I can do to support’,” Sonia says, recalling the process.

All the support encouraged them to go even further. They wanted their movement for women’s freedom to grow and decided to launch the Collective 490 with one big push: “Launch day was crazy. All the media we worked with and all the women involved all posted at the same time. It blew up! Suddenly, the petition was everywhere on social media and news media. Quickly we had 5000, then 10,000 signatures.”

The power of online solidarity leading to change

The effects of the media collaboration and social media exposure were clear. “From that day, women from the movement were speaking up on radio, television, newspapers and everywhere they could. There were a lot of women’s voices that were suddenly heard all around. The only thing Leila and I did was to give them a gentle push to speak up, but they were the ones leading and letting their voices be heard.”

“I saw that when a woman empowers herself, she empowers everyone around her. And that what it’s all about.”

“We got so much press. It felt like the whole world was talking about us. We couldn’t be ignored anymore,” Sonia happily exclaims. Soon after, the French newspaper Libération put them on their front page as well. Two days after, Morocco’s King Mohammed VI freed Hajar Raissouni, her partner and her doctor. “They couldn’t keep them in prison. It was just too bad for the image of the country,” she says and continues: “We had been so successful in getting attention for our message through news media and the Internet that now we were actually getting closer to our long-term goal: changing the law. It was huge for us.”

The Collective 490 started receiving hundreds and hundreds of stories from especially young women who felt violated by these laws, and they started to share them in the movement’s online communities. “For me, this was so important. All my work is about the youth and giving a voice to youth, and now, with our platforms, we are transforming into a media for all these young Moroccans – not a traditional news media, but an online, community-based one. And this is the media I really believe is the future,” she says.

From her work at Jawjab, and especially with its video channel for young women, Sonia had experienced the impact that the Internet can have, and she drew on these experiences for her work with Collective 490: “I had experienced how sharing personal stories – and a great number of them – could change things in real life. And I saw that when a woman empowers herself, she empowers everyone around her. And that what it’s all about.”

In 2019, Sonia Terrab and Fatim-Zahra Bencherki visited the Youth Democracy Festival in Copenhagen with IMS. They talked breaking taboos, online medias and the youth’s strength to shape the future with the many young Danes attending.