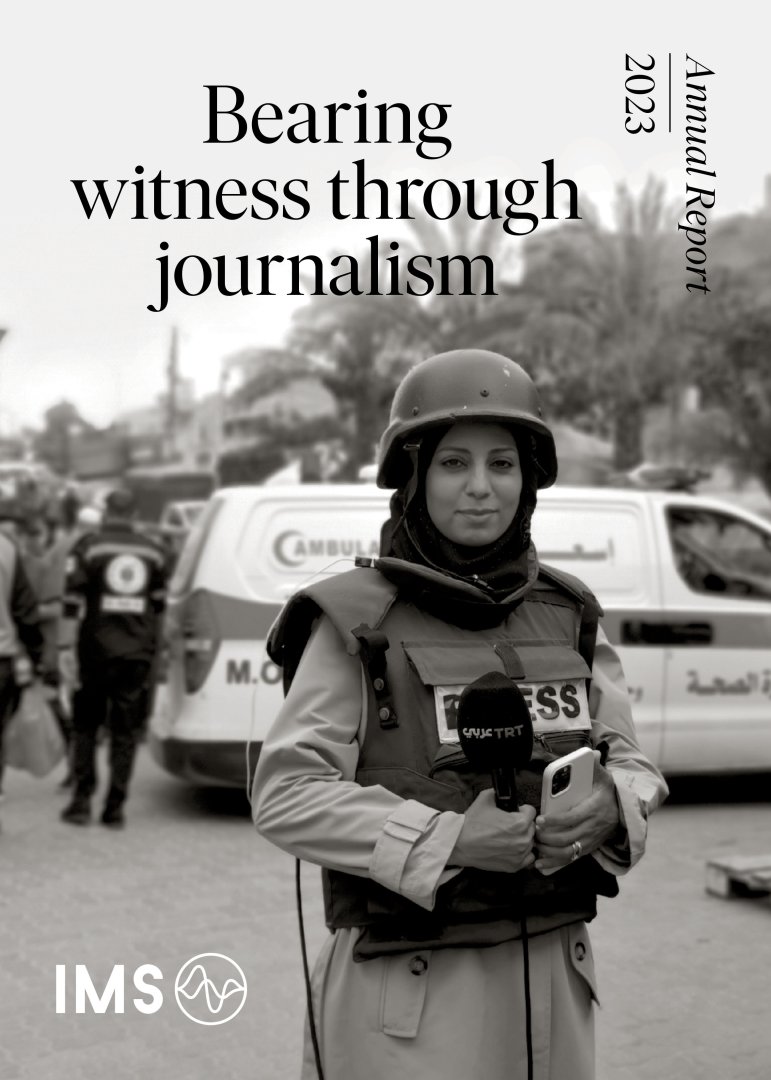

Sara Alyakin of Al-Jumhurya.

IMS Annual Report 2023

Supporting journalists and media outlets in exile

The global slide towards authoritarianism is forcing journalists and media outlets to work from exile, but they have found ways to keep their audiences engaged and informed.

Independent media hold an important space for a continued free, democratic and pluralistic debate. But in cases of sudden political transition or growing totalitarian rule, media operations often have no choice but to move outside of their home country; it’s often the only way to secure their own safety and to make sure the public still has access to independent journalism and reliable facts. For these reasons, IMS engages with exiled media and journalists, despite their immense organisational and personal challenges. IMS have assisted the establishment of media outlets in exile and supported exiled journalists from Myanmar, Afghanistan, Ukraine, Syria, Belarus and Zimbabwe. Many are still in exile, but some have been able to return home.

“It takes a lot of work to establish a media while you are also a refugee,” says the CEO of a significant Asian media outlet which was set up in exile and now works through a hybrid approach with many reporters still inside the country it serves.

“We were filling out our asylum papers and building a media house. We were queuing for our drivers’ licenses and building a media house. Looking for co-signers for our accommodation and building a media house. We were sending our kids to new schools and learning a new language and building a media house.”

An abrupt political transition meant that there was suddenly no opportunity to run an independent journalistic outlet registered inside the country. Despite the difficulties of setting up a media operation in exile, the CEO saw this as the only way to keep serving audiences with journalism that could inform and educate.

“After the political developments, we did not lose our profession, we did not lose our beliefs, we did not lose our ethics. But we did lose our platforms. So, in order to serve the people and our audience, we needed a new platform where journalists could come together. A platform that is free of political and financial influence. This platform could only be legally protected outside our country’s borders.”

IMS uses our years of experience to support exiled media on different stages of their journeys, aiming to nurture networks, cooperation and knowledge exchanges between our partners working in exile, hybrid or diaspora contexts. Our support takes a comprehensive approach, encompassing technical solutions, psychosocial support and business development.

Working, living and producing content in exile is incredibly volatile, demanding journalists and managers to constantly evolve and adapt. When their website gets blocked, IMS might support them in creating content native to social media. When internet or power supplies in their home country are weak, we help them distribute their stories through podcasts that better serve audiences hampered by inaccessible internet. If their registration or work permits are contested or revoked in their host countries, we provide legal assistance.

Leaving the “kingdom of silence”

For our Syrian partners, the personal toll of their situation has not necessarily gotten easier though many have been working in exile for years.

Founded in 2012 by a small group of journalists, writers and academics, Al-Jumhuriya has since established itself as a key source of high-quality reportage and analysis and a platform for critical thinking and democratic values. Al-Jumhuriya’s audience are Syrians who still subscribe to the general ideals of the uprisings in 2011 whether they are now part of the diaspora or still inside the country.

Al-Jumhuriya grew out of the Syrian people’s peaceful demands for political freedom and basic human rights along with many other independent outlets. Prior to 2011, Syria had been a “kingdom of silence” with only a handful of state owned and state-operated newspapers available since the Baath party came to power in the early 60s. When it became clear around 2014 that the protest movement had been defeated, Al-Jumhuriyah saw only two options: to return to the kingdom of silence or to move part of their operation outside of Syria.

Al-Jumhurya’s relevance to audiences in Syria and its role in fostering democratic ideals became clear in August 2023. Despite enormous safety risks and contrary to all expectations, new protests emerged in the province of Sweida.

“Obviously state media controlled by the Syrian regime is not going to cover this,” says Karam Nachar, co-founder and Chief Executive at Al-Jumhuriya.

“We immediately reached out to the organisers of this movement who are functioning under enormous security threats and asked for an interview. And their response was: ‘We grew up reading Al-Jumhuriya. We love your content. This is how we think politically about Syria,’” says Karam Nachar.

Outside and inside: the important division of labour

Despite the personal, organisational and practical challenges of running a media outlet in exile, Sara Alyakin of Al-Jumhurya sees it as necessary in the context of Syria.

“Syria is literally one of the most dangerous countries for journalism and journalists in the entire world. I think having a life source outside the country is very much a symbiotic relationship. I do not think it is a dichotomy of those who are inside versus those who are outside,” she says.

Because the organisation has many reporters and writers still inside Syria, they contest the exiled media label.

“We are very much a hybrid organisation. We have our colleagues inside Syria and we have our editorial team outside Syria. Our editors receive stories from inside and then weave them together. The ones of us in exile, we have relative liberties compared to the people still living under the very repressive regime. We use those liberties in a way so that our efforts still go back to Syria. There is a natural division of labour there between the ones that are inside and the ones that are outside.”

Bad businesses – great investments

Among the many challenges of exiled media is that ad revenue and other monetisation methods are difficult to come by. Their audiences are scattered around the world and their data is flawed or irretrievable because audiences inside the country use VPNs and other tools to hide their engagement with the journalism due to fear of reprisals. Furthermore, paywalls would make journalism unavailable to audiences who do not have the funds – or simply a credit card – to pay for media.

IMS’ exiled media partners generate only three to seven percent of their revenue from commercial sources. As their partner, IMS are realistic about their poor prospects for sustainability. We provide long-term core funding to our partners, which is essential for exiled media to establish themselves, survive and thrive.

Media working in exile or hybrid setups are not good businesses, but they are excellent investments in promoting fundamental freedoms and democratic values.

Small independent media outlets are up against heavily funded state propaganda machines; in comparison, the costs of running these media outlets are drops in the ocean. Kremlin documents leaked earlier this year revealed a budget for over $1 billion allocated to Putin’s propaganda and information war. Influencing public opinion and controlling political narratives is hugely important for totalitarian regimes, whether it be the Taliban, the Assad regime or the military junta in Myanmar.

What do we lose if we lose exiled media?

The latest report from V-Dem Institute shows that government censorship of the media is worsening in 47 countries. Exiled media are often the only ones who are in a position to push for political accountability and foster democratic conversation.

“Media is integral to every single developmental and humanitarian effort of Syrian civil society and without it there is no conversation. We cannot dream of a future democratic Syria if we have no information, we have no facts, we have no data, we have no analysis. We are left with only propaganda. And you cannot create a democratic society based on propaganda,” says Sara Alyakin.

Download the full IMS Annual Report 2023